Seemingly clinging to a creaky branch, Mylan’s embattled CEO Heather Bresch on Thursday defended her company’s widely panned price hike of EpiPens, assigning blame instead to an “outdated” U.S. health care system.

But what Bresch also failed to shoulder is the company’s responsibility for aggressive marketing tactics that have led to the overall perception that the Mylan EpiPen is an essential first aid device that no one should be without.

The glossy marketing campaign for this life-saving emergency device has included high-profile figures such as Sarah Jessica Parker—who announced Thursday that she has “ended my relationship with Mylan as a direct result” of the price hike—$35 million on TV advertising in 2014, (up from $4.8 million the year before), plus a $2 million blitz during the 2016 Summer Olympics.

The television ads, which stop short of fear-mongering but that strike an ominous tone, warn viewers that “Every six minutes, food allergies send someone to the hospital. Always avoid your allergens, and talk to your doctor about a prescription treatment you should carry for reactions.”

In 2012, Bresch spoke to The New York Times about her plan to make emergency epinephrine injectors more widely available in public places. Doug Tsao, a pharmaceuticals analyst, told the Times that he believed this outreach was essentially a Trojan horse for generating demand for the product.

Related: Mylan CEO's Pay Rose Over 600 Percent as EpiPen Price Rose 400 Percent

“When the school nurse uses EpiPen, what does the nurse refer parents to?” Tsao said. “I think that is absolutely part of the motivation.”

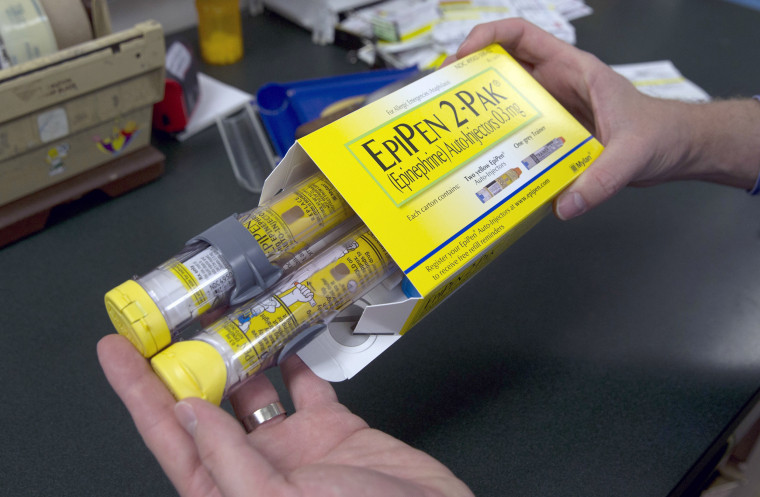

One element of Mylan's outreach efforts is to advise patients to double up on EpiPens—information that is parroted by doctors, parents and school nurses who repeatedly fear that “something could go wrong with your first attempt at giving the shot.”

Michael Pistiner, a pediatric allergist at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, told NBC News, “As the father of a child with a food allergy, it is challenging [to afford an EpiPen] even for me…. Let’s pretend I used one on my kid last week. I have to buy a double pack to replace it. Why do I now need three sticks?”

Though a small number of patients do require a second dose, it would appear the device is mainly sold in packs of two due to imperfect product design: A recent study conducted by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology that compared the EpiPen to a competing product, the Anapen, concluded that the EpiPen is the most difficult type of auto-injector to use.

The study showed that even after one year of training on the product, 14 percent of parents still accidentally stuck the needle in their own thumb instead of in their child’s leg, as compared to zero percent of parents using the Anapen (which is not available in the United States).

Related: As EpiPen Backlash Grows, CEO's Link to U.S. Senator Draws Scrutiny

In fact, the emergency device is so difficult to use that Mylan employs a special team of trainers to teach school staff and first responders how to use it; those teams have also come under scrutiny: At least one of the three authors of a 2012 paper that said people forget how to use EpiPens after about three months and require additional retraining disclosed financial ties to Mylan in a subsequent academic study, according to ProPublica.

And yet the basic design of the EpiPen has not changed since 1980.

“The EpiPen has a number of problems in its form, function, and appeal,” said Michael Langan, a physician who is working on an alternative epinephrine injector named the EpiBracelet. Langan said Mylan's bulky Sharpie-shaped device is viewed by older kids as “burdensome” and “a visual reminder that they are ‘different’.”

“These problems contribute to incorrect use, misuse, not carrying the unit as prescribed (non-compliance), and can result in an adverse outcome including death. Flawed design of medication delivery devices promotes user error which can result in adverse outcomes,” said Langan.