Fidel Castro was so desperate about Cuba's financial situation at the start of the 1980s that he turned to a banker from the country he hated the most, the United States, to get advice on restructuring the country's heavy debt load.

"It was the year the of Marielitos"—the 1980 Cuban boatlift—"and he was under a lot of strain to be able to service the debt to the European banks who had lent to him, and also to some Canadian banks," said Bill Rhodes, a former Citigroup executive and author of "Banker to the World." Rhodes was the bank's point person on Latin America for decades.

Rhodes told CNBC he agreed to the meeting at the behest of then-Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega, who knew Rhodes because he was representing the banks in the negotiation of the Central American country's debt restructuring.

"He asked to see me. I didn't ask to see him," Rhodes said.

During Rhodes' meeting with Castro, the Cuban leader made some startling admissions.

Among them: Castro told Rhodes he regretted kicking the International Monetary Fund out of Cuba in his early days of the communist revolution.

Read More: US embassy officially reopens in Havana, Cuba

Rhodes recounted that Castro told him Cuba should have stayed a member not only of the IMF, but also the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. "And he said that was a poor decision, because they're institutions that could have helped Cuba, you know, in our economic problems."

The IMF, based in Washington, has long been controversial and never more so than recently due to its involvement in the Greek financial crisis. The current leaders of Greece have criticized the institution and tried to eliminate its involvement in the Greek economy.

Long-time Cuba followers may be even more startled by Castro's other admission: that he felt it was a mistake to put Ernesto "Che" Guevara in charge of the Cuban central bank.

"He said, 'Why I ever did that, I don't know, because obviously Che Guevara knew nothing about finance and banking,' but he said, 'I put him in there because I guess I trusted him. But it was a mistake,'" Rhodes said.

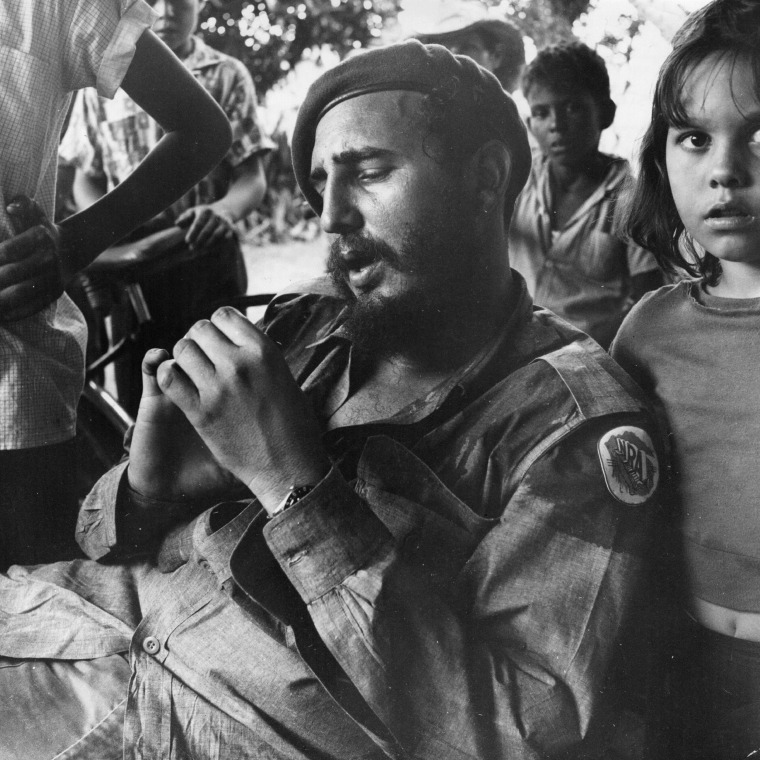

"Che" Guevara is perhaps the best-known figure from the communist take-over of Cuba, after Fidel himself. Guevara was killed by Bolivian troops in 1967, but his idealized visage, in beard and beret, is still sold on T-shirts around the world.

Read More: Very patient investors hope to get paid on Cuban debt

His influence remains strong with the world's leading socialists. The current Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras named his son Ernesto in honor of Guevara.

Before he became a central banker, Guevara was in charge of killing political enemies of the new government. He oversaw the torture and execution by firing squad of hundreds of political prisoners at the notorious La Cabana prison, earning him the nickname the Butcher of La Cabana.

He became Cuba's central bank chief in November 1959.

Less than a year later, on a Friday afternoon in September 1960, Guevara used armed militias to seize all American banks in the country. Those included six branches of the National City Bank of New York (now Citigroup), the National Bank of Boston (Now Bank of America), and Chase Manhattan (now JPMorgan Chase). All three banks have outstanding claims against the Cuban government as a result.

Largely as a result of ideology-based policies espoused by Guevara, Castro asked for help with Cuba's debts when he met with Rhodes. In his book, Rhodes writes "I advised Castro that he had to go about it in an organized manner, with representatives of the banks involved, in order to ensure the country's reputation in international capital markets."

Castro carried out the restructuring but subsequently defaulted on that agreement. An estimated $5 billion from the mid 1980s remains outstanding when past due interest is included. That debt has been bought up over the years and is now held largely by a small group of London traders and hedge funds, who are waiting for the day when Cuba will finally settle it.

Castro also told Rhodes he didn't think Cuba owed Citigroup any money for the seized banks because Citi had frozen Cuban assets held in New York. On Friday, the day the U.S. reopened its embassy after 54 years, Castro appeared to elaborate on that position when he argued in an essay in a Communist Party newspaper that the United States owes Cuba "many millions of dollars" in damages from the trade embargo imposed on the nation for half a century.

Castro also complained in the essay about the United States removing the U.S. dollar form the gold standard in 1971.

Back in the 1980s, Rhodes explained to Castro that he disagreed with him about debts to Citigroup, telling him "maybe you think it's equal, but I don't think it's equal because there's still a lot outstanding. We felt that the government of Cuba owed us on loans that we could not collect because they were nationalized."

Looking back on it, Rhodes said, "it was a fascinating conversation."