Where some people saw a hole in the ground, Brent Zettl envisioned a farm.

As president and CEO of Saskatchewan-based Prairie Plant Systems, a biotechnology company that produces engineered plants for medical purposes, Zettl needed a nursery where the environment could be closely regulated and sealed off from predation or contamination by other plants, fungus or bugs. He found all that in an abandoned copper mine in White Pine, Michigan.

"You don't want some of them to go missing or get a disease," he said of the genetically modified legumes and mustard plants growing under banks of 1,000-watt lights in a 2,500-square-foot underground chamber.

Although abandoned mines are better known for the environmental and economic problems they sometimes cause, enterprising businesses are finding ways to breathe new life into old diggings. Increasingly, the tombs that once provide the raw ingredients of the Industrial Age are home to distinctly 21st century innovations, from Zettl’s pharmaceutical-grade plant nursery to electronic data storage and green energy. Other entrepreneurs are turning the gashes in the ground into tourist or recreational attractions.

Not every mine is easy to re-purpose. Many are polluted with toxic tailings — materials left over after being separated from the valuable ore — acid mine drainage, as the run-off is called, or both. They also can pose a risk of explosion — from dangerous methane pockets within old coal seams, for instance — or collapse.

Related: Ticking Time Bombs? Abandoned U.S. Mines Pose Toxic Spill Danger

And cleaning an old mine is neither easy nor cheap, as this summer's spill of toxic sludge from the Gold King Mine near Silverton, Colorado, demonstrated. In that case, a private contractor working for the Environmental Protection Agency accidentally released some 3 million gallons of rust-colored sludge from the gold and silver mine, which ceased operations in 1922, on Aug. 5 during clean-up efforts. The spill fouled rivers in three states. On Oct. 23, government investigators blamed the EPA for the accident.

Despite such potential drawbacks, many old mines offer a surprisingly hospitable environment to do business.

Prairie Plant Systems occupies what is called a "decline mine," meaning that the entryway is a sloped ramp rather than a vertical shaft to the growth chamber several hundred feet underground.

“It’s like Indiana Jones until you get to the chamber.”

For workers who tend and harvest the plants, it's anything but a typical commute: They have to change into mine safety gear, ride down the ramp in a diesel-powered truck or utility vehicle, then change again into clean clothes — to avoid contamination — when they reach the growth chamber.

"It's like Indiana Jones until you get to the chamber," Zettl said.

The underground beds offer multiple advantages. The plants thrive in a controlled environment — with a consistent ambient air temperature of 52 degrees Fahrenheit — and Zettl said the company saves about 10 percent in electrical costs over above-ground greenhouses.

The warren of underground tunnels and rooms also has more space than the company could ever need.

"We have a 35-square-mile area underground — that's how big the mine is. We're not going to run out of space," Zettl said. Currently, the company is working on a 15,000-square-foot expansion, he added.

Other retired mines are being put to even-more-futuristic uses.

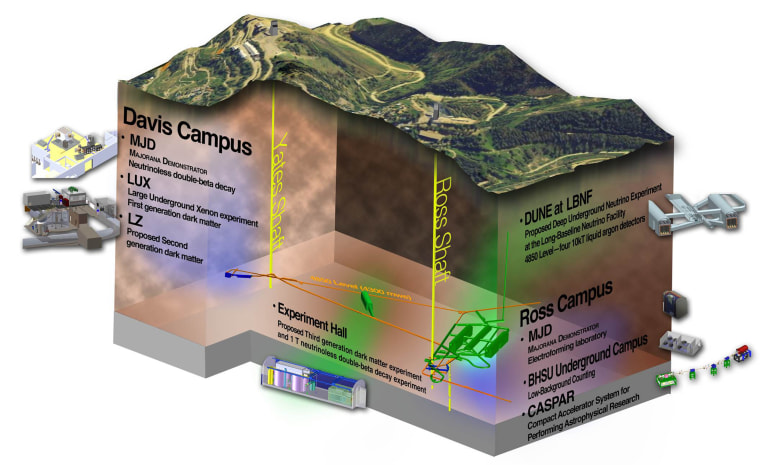

A former gold mine in Lead, South Dakota, is now home to the Sanford Underground Research Facility, a vast underground physics lab where scientists study little-understood ideas such as dark matter and subatomic particles.

The site was given to the state, which committed $40 million to build the lab, in 2006 by previous owner Homestake Mining Co.Philanthropist T. Denny Sanford also chipped in $70 million, which explains why his name is on the marquee.

The Department of Energy foots the roughly $15 million a year expense of running the facility, which includes basic operational costs as well as the expense of treating and pumping out the water that accumulates more than a thousand feet beneath where the scientists work, about 4,800 feet below the surface.

Roughly 16 experiments, primarily in physics but also in biology, geology and engineering, are being conducted at the facility. And in August, crews began installing equipment for the underground lab’s Compact Accelerator System for Performing Astrophysical Research, otherwise known as CASPAR. Scientists there hope to have it up and running by next year in order to begin plumbing the mysteries of deep space from deep within the Earth.

"When you're looking to the universe for answers, it seems really counter-intuitive to look underground," said the lab’s communications director, Constance Walters. But burying the lab a mile deep in the Earth is the only way to shield experiments from the interference of the sun's cosmic rays, she said.

Concerns inside the former mine in upstate New York where the document and data storage company Iron Mountain set up shop are decidedly more terrestrial. The company, which took its name from the disused iron mine where it set up shop in 1951, stores valuable and classified information of government agencies and Fortune 500 companies.

“If you want to take photos and store them for 20 or 30 years, you can do that … but if you have a long-term plan for 300 years or more, it’s very difficult to do in an above-ground facility.”

Doug Berry, vice president of project and facility management at Iron Mountain, said that up to 270 feet of limestone provide a nearly unparalleled level of security, on top of the measures typical of above-ground facilities, like guarded gates and locked vaults.

"It's not like a data center where you'd potentially have the ability to drive up to it," he said. Vital records, along with historical prints, recordings and documents, are protected in another sense by the darkness, cool temperatures — about 56 degrees, Berry said — and low humidity.

"If you want to take photos and store them for 20 or 30 years, you can do that … but if you have a long-term plan for 300 years or more, it's very difficult to do in an above-ground facility," he said.

For digital-age data, Iron Mountain expanded one of its existing facilities in an old limestone mine in Boyers, Pennsylvania, five years ago.

Related: Australia Approves One of World's Biggest Coal Mines

Digital storage — the burgeoning amount of text, pictures and other material we keep stored "in the cloud," actually giant banks of servers — is a challenge because the machines generate so much heat. Having to continually run high-powered heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems can be expensive when the data is stored above ground.

"The electrical (cost) associated with HVAC — that's a large use of the electricity load in a typical data center," Berry said. Room 48, as Iron Mountain's facility is called, is an exception, thanks to the large, naturally occurring pool of water in the mine's "basement."

"It's basically an underground lake, acres of water at a pretty cool temperature that we pull and use it for all of our cooling purposes," Berry said. After being pumped through the system, the water is discharged back into the lake to cool off and be reused later. As a result, Room 48 uses about 60 percent of the power a traditional data center would require.

Fun in the dark also has given a few old mines new life as underground tourist destinations, from a limestone mine in western Pennsylvania now crisscrossed with ATV trails 250 feet below ground, to an underground bike park in Kentucky to trampoline and ziplining courses that run through two slate mines in Wales, U.K., abandoned almost 200 years ago. Former salt mines in Europe and South America house cathedrals, and one, in Romania, even holds an underground theme park.

The attractions can help breathe fresh air into what are often moribund local economies, said Johara Sykes-Davies, manager of business development at the underground Zip World attraction in Wales.

"For many towns and villages in Wales, the closure of mines of all varieties has considerably affected the local economy," he said via email.

Zip World runs two adventure-tourism mine attractions, Zip World Caverns and Bounce Below, a network of trampolines, walkways, slides and tunnels, all made from netting.

"Making use of disused mines such as this (has) had a massive impact on the local economy," Sykes-Davies said. "Renewed industrial landscapes such as this have given a new sense of purpose to otherwise disadvantaged areas."

While many communities might welcome such investments, setting up shop in an old mine isn't an easy task.

To start with, there is no central repository for retired mines, so finding one that might fit particular needs is difficult.

"The problem here — and this is the insidious part of abandoned mine lands — is that mines are not well mapped in this country," said Chris Holmes, a spokesman for the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE).

The agency does maintain a database of abandoned coal mines, listing their relative degree of hazard, but even that requires frequent updates. "You’d think the database would be fairly static, but that's not true," Holmes said. Instead, he said, mines are often found by happenstance or accident and added to the list.

Unfortunately for would-be subterranean entrepreneurs, old coal mines, although plentiful, often aren’t good candidates for reuse, so much of the reuse of old coal mines takes place on the surface. Companies don't want to risk stumbling across acid mine drainage, as the polluted water is called, or an explosive methane pocket deep within a coal seam.

In addition to pollution and explosion threats, many are prone to collapse.

Related: Last Residents of Picher, Oklahoma, Won't Give Up the Ghost (Town)

"Coal mines are notorious for being unstable, and that's because they're all in sedimentary rock," said Alfred Whitehouse, a consultant on mining and environmental issues and former administrator of the Abandoned Mine Land Program at Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. "It's more complicated because on land when you frame a building, you can see what you're doing. When you're underground you're not quite sure what's above you," such as weak zones or fractures in the rock.

The stability problem is exacerbated, according to Eric Cavazza, director of Pennsylvania’s Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation, by the fact that many mine owners removed beams supporting walls and ceilings when they departed.

Despite the challenges, some abandoned coal mine sites have been turned into parks and green spaces, golf courses, even a honeybee farm in Kentucky.

Businesses willing to take on a coal-mine makeover also may be eligible for attractive incentive: Coal producers pay a per-ton fee to the federal government that gets doled out to the states for cleanup projects. Since 1977, the agency has disbursed about $8 billion in coal mine-cleanup funds.

Some experts say they also expect expanded use of old mines in coming years in the field of green energy production, as they have at least a legacy connection to the electrical grid.

Related: Who Digs Solar and Wind Power? That's Right: Miners

"There's a real opportunity there for this kind of conversion," said Whitehouse, the consultant and former federal mining official. "...A lot of mines are in the middle of nowhere so they're not as well suited to what you might think of as commercial enterprise. But if you want to do a large solar field, all you need is a lot of sun. To me, it makes real good sense."