It is designed to be an icon — and unlike any bridge in the country.

After years of debate and delays, the dramatic new eastern span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge is finally taking shape.

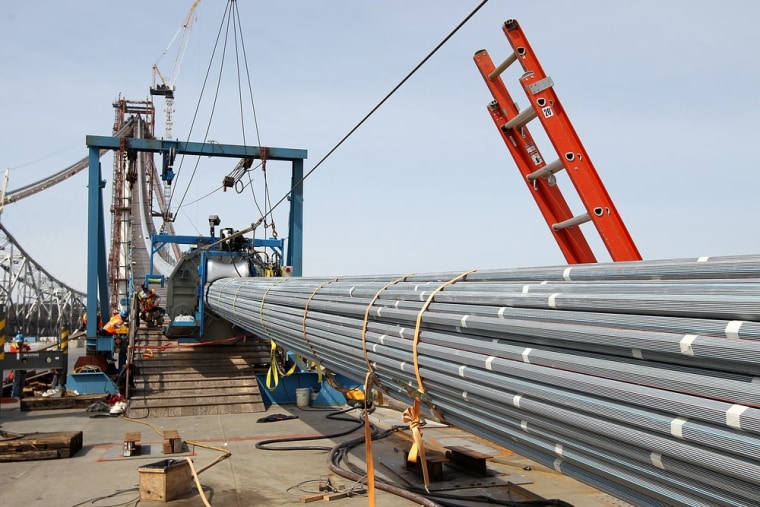

At the heart of the project is a unique “self-anchored suspension span” — twin roadways linked to a soaring, 500-foot tower by a single, mile-long cable.

A little over a year before the bridge’s scheduled opening, the bridge is already a conversation piece, though not for the reasons planners had hoped.

Instead of marveling at the design, what many are talking about is the fact that the suspension portion of the bridge was made in China.

Critics say the decision to outsource the span — the central tower and the two 1,500 foot steel road decks were fabricated in a specially-built factory in China and shipped to San Francisco Bay — was a missed opportunity to create thousands of American manufacturing jobs.

California officials contend the U.S. does not have the manufacturing capacity or the workforce to build such a project on its own.

A CNBC Investigations Inc. review of the process has found miscommunication, misconceptions and missteps that have, at the very least, tainted what planners had hoped would be an architectural and engineering triumph.

“The Bay Bridge: 100% foreign steel,” proclaim billboards along the freeways approaching the bridge. To be accurate, the suspension span of the bridge is only about 80 percent foreign steel according to the California Department of Transportation (also known as CalTrans), and the entire eastern span, from Yerba Buena Island to Oakland, is about 20 percent foreign.

The Alliance for American Manufacturing, which sponsored the billboard campaign, says whatever the actual content, the decision to use Chinese steel was scandalous.

“I think every California taxpayer should be outraged by this,” says executive director Scott Paul.

But the outrage extends beyond California.

“What is it about American regulations, American taxation, American labor cost and attitudes that makes it cheaper to go to China,” asked former House Speaker Newt Gingrich when asked about the bridge at a CNBC Republican Presidential Debate in November.

“It is good for America to have free trade,” said former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney — now the presumptive GOP nominee — at the debate. “But China is playing by different rules.”

CalTrans Bay Bridge Program Manager Anthony Anziano told CNBC in an interview that the state had no choice but to go overseas.

“The largest companies in this country just simply didn’t have the capacity to be able to do that work in the time that we required,” he said.

That point remains a subject of bitter debate. And with the project now near completion, it is not clear the decision to outsource the span yielded anything close to the savings officials had hoped for.

Now budgeted at more than $1.75 billion for the suspension span alone, the section has encountered nearly $300 million in overruns. And while officials recently moved up the projected opening of the bridge to Labor Day 2013, it is still as much as a year behind the schedule that was planned when the contract was awarded.

In the end, the time and budget is nearly identical to the single bid the state received to build the bridge with American steel: a five-year, $1.8 billion proposal by a joint venture of American Bridge Company and Fluor Corporation that the state rejected in 2004.

There is no way of knowing what overruns that proposal would have encountered, and it, too, contemplated buying some of the steel from overseas. But independent steel industry analyst Michelle Applebaum says American firms have a better track record than the Chinese when it comes to bringing in large projects without major overruns.

“Just looking at dollars and sense, there was a much better argument for this to be done domestically,” says Applebaum, who describes herself as an ardent free-trader.

And she says any cost advantage the Chinese might have had would easily have been made up by the benefits to the U.S. economy. She believes officials in California fell victim to a mindset that says China is automatically cheaper.

“We shot ourselves in the foot,” Applebaum said. “We never even took seriously the domestic bid.”

Not so, says Anziano. But with only one domestic bid, which came in at more than double the CalTrans engineers’ estimate, the state had a duty to look elsewhere.

“That’s telling you there’s something wrong. You’re not getting competitive bidding,” he said.

Opening the project to foreign competition was not a simple matter. It required some fancy legislative footwork that still angers some U.S. manufacturers, who saw the Bay Bridge as a unique opportunity to revitalize American manufacturing just as the nation was heading into a recession.

Early on, some in California saw the Bay Bridge project — necessitated when the existing bridge was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake — as a potential job creator.

Flush with wealth from the dot-com bubble, the state and Bay Area leaders mandated the new bridge be “iconic” in its design. The costs — and potential benefits to the winning bidders —ballooned.

After lobbying from labor and industry groups, then-governor Gray Davis won federal funding for the bridge. That meant the project was covered by a 1982 “Buy America” law requiring the state to give preference to American contractors.

But then the 2004 bid came in, just months after the new governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, took office. Hit by sticker shock, the Schwarzenegger administration decided to regroup.

“One of the things that stuck out was the Buy America component,” Anziano said. “That was restricting, and we heard this loud and clear from the construction community.”

So the administration reconfigured the funding formula for the 16 separate contracts that made up the Bay Bridge project. While most of the contracts would continue to receive federal funds and be subject to the Buy America requirement, the self-anchored suspension span — the signature segment of the project and by far the most lucrative — would be paid for with state and local funds, exempting it from the requirement.

Last month, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill that would ban such a maneuver in the future. It faces an uncertain future in the Senate. Regardless, it comes years too late for some who had hoped to win the Bay Bridge project, until the state changed the rules.

“We thought it was gamesmanship, that it was a way of getting around the system,” says Thomas Hickman, a vice president at Oregon Iron Works outside Portland.

CNBC.com: Jobs employers can't fill

His firm was part of a consortium, Bay Bridge Fabricators, that had been preparing a bid for the project. The proposal included a new, state-of-the-art fabrication plant to be built at the port of Vancouver, Washington. Hickman says the factory would have been a huge boost to U.S. manufacturing capacity, allowing American firms to compete for even bigger projects around the world.

“The impact on the economy throughout this country would have been tremendous,” he said.

But when state officials announced in 2005 that the suspension span would no longer be subject to the Buy America requirement, the plan died.

“At that point, we all looked at each other and said it's really time to go home,” said Hickman, “Because they're determined to go to China, or Korea, or somewhere other than the U.S. for this bridge.”

“That was not part of the thinking — let’s just send it overseas,” said Anziano. “It was the reality of the market.”

Nonetheless, Schwarzenegger and his administration began actively courting foreign bidders. In 2005, Schwarzenegger traveled to China on a trade mission. During the visit, state transportation secretary Sunne Wright McPeak ceremonially presented officials with a set of CDs including bidding specifications for the Bay Bridge project.

From the state’s standpoint, the strategy worked as planned — increasing competition. When the project was rebid in 2006, the American Bridge-Fluor joint venture won out. Unencumbered by the Buy America law this time, the group bid $1.43 billion, nearly $400 million below its 2004 bid. After winning the contract, the group promptly subcontracted the steel fabrication to ZPMC, a Shanghai-based firm whose primary expertise is building cranes.

“I don't believe they ever really took a fair look at what was available here in the United States before they made the decision to effectively abandon the U.S. as a supplier of the structural steel for the bridge,” Hickman said. “I don't mean that to sound harsh, but at the same time, that's really exactly what they did.”

His firm did win a contract to build some components of the Bay Bridge, but he says it is nothing compared to the contract for the suspension span.

State officials say the bidding results proved the U.S. did not have the capacity to build the bridge on time and at a reasonable cost, and they could not rely on a hypothetical U.S. factory to build such a vital span. But it is not clear China had the capacity either.

Soon after winning the contract, ZPMC built its own new factory in China, just as Hickman’s consortium had planned to do in the U.S. And more than 200 American experts and engineers traveled to China to help supervise the project.

“Building a new facility, which they had to do, training their people, which they had to do, all of those were an investment in China that in my mind should've been done here,” Hickman said.

“It's not quite that simple,” said Anziano, who says it is unfair to blame CalTrans for the work going to China. “You have to keep in mind, first of all, that the capacity situation that we have in this country is something that has evolved over decades. You can't fix it overnight. You really can't fix it on the back of one single project.”

Besides, the Chinese managed tobuild their plant in just eleven months, American Bridge’s then-CEO Robert Luffy told a Congressional committee in 2007.

CNBC.com: Ultra wealthy shunning stocks

“Believe me, they have the capacity,” Luffy testified. “It is beyond your comprehension if you haven’t been there.”

But he acknowledged that had the state approved the venture’s initial bid in 2004, it would have added the capacity in the U.S.

“A lot of additional capacity,” he said.

Today, one more major Bay Bridge contract has yet to be awarded: a five-year, quarter billion dollar project to tear down the existing bridge. Among the rumored bidders: a firm from China.

This story originally appeared on CNBC.com.