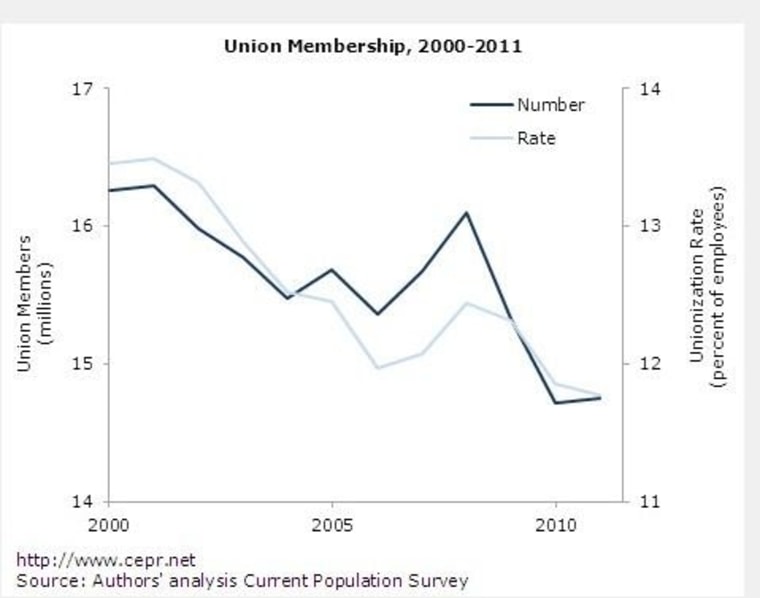

The downhill slide in U.S. union membership has stalled.

After steep declines since 2008, the unionization rate leveled off last year, pointing to what is either a number that just can’t go any lower, a lull in yet more union membership hemorrhaging, or the beginning of a labor turnaround.

Union membership plummeted by nearly 1.4 million workers between 2008 and 2010, but “hit a plateau in 2011,” according to the Center for Economic Policy Research, an economic think tank that reviewed data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The private sector led the way with a union membership increase of 110,000 employees, while the public sector saw a 61,000 decline, mainly due to government cutbacks.

The data shows a stabilization following years of unionization declines, but could it be the early signs of a union renaissance?

“No, not yet,” surmised John Budd, a professor of work and organizations at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management and director of the Center for Human Resources and Labor Studies.

“We’ve reached a core group that doesn’t have much left to shrink,” he said, about traditional unionized workers in industries such as auto, airlines, and healthcare. On the other hand, he added, it could be a sign “people are turning to unionization again.”

The growing perception among many that economic inequities are rampant could fuel a rethinking of the role unions can play, he maintained. “That’s something that unions fight for, equality and economic fairness,” he said. “In terms of workers getting frustrated and unions turning the corner as a result, the signs of that potential have been around for a number of years now.”

A positive sign, he noted, is that in a political environment that has vilified organized labor and has spawned movements to hamper organizing rights in states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin, membership numbers have stabilized.

Others aren’t as hopeful.

Gary Chaison, professor of Industrial Relations at Clark University’s Graduate School of Management, believes the worst is yet to come. “There will be greater layoffs in the public sector as cities and states have to lay off workers to narrow the budget shortfalls caused by excessive pension obligations,” he said. “And as the economy stalls, perhaps the result of continuing high employment and low consumer confidence, or the banking crisis in Europe, employers in manufacturing will be reluctant to add to their workforces.”

Here are some details of the CEPR report:

- The largest net increases in unionization came from health care and social assistance; construction; and durable goods manufacturing.

- The biggest declines came from professional and business services; utilities; and non-durable manufactured goods.

- Florida saw the biggest gains in union members in 2011; followed by Michigan Colorado, Illinois and Missouri.

- New York, the most heavily unionized state, saw the sharpest drop, followed by California.

Overall, women represented the biggest increase in union membership with an increase of 36,000 female members, compared to about 12,000 men.

“I don't think that men or woman have a greater natural propensity to join unions, but it's all about industry,” Chaison said. “Apparently there have been fewer job losses or health care occupations or service occupations -- hotels and restaurants -- dominated by women.”