By Barbara Raab, Senior Producer, NBC News

Five years after the depth of the Great Recession, at a time when the wealth gap in America is at extremes – a new analysis finds it at its widest point since the Roaring 20s – journalist Sasha Abramsky has a new portrait of one end of that great divide.

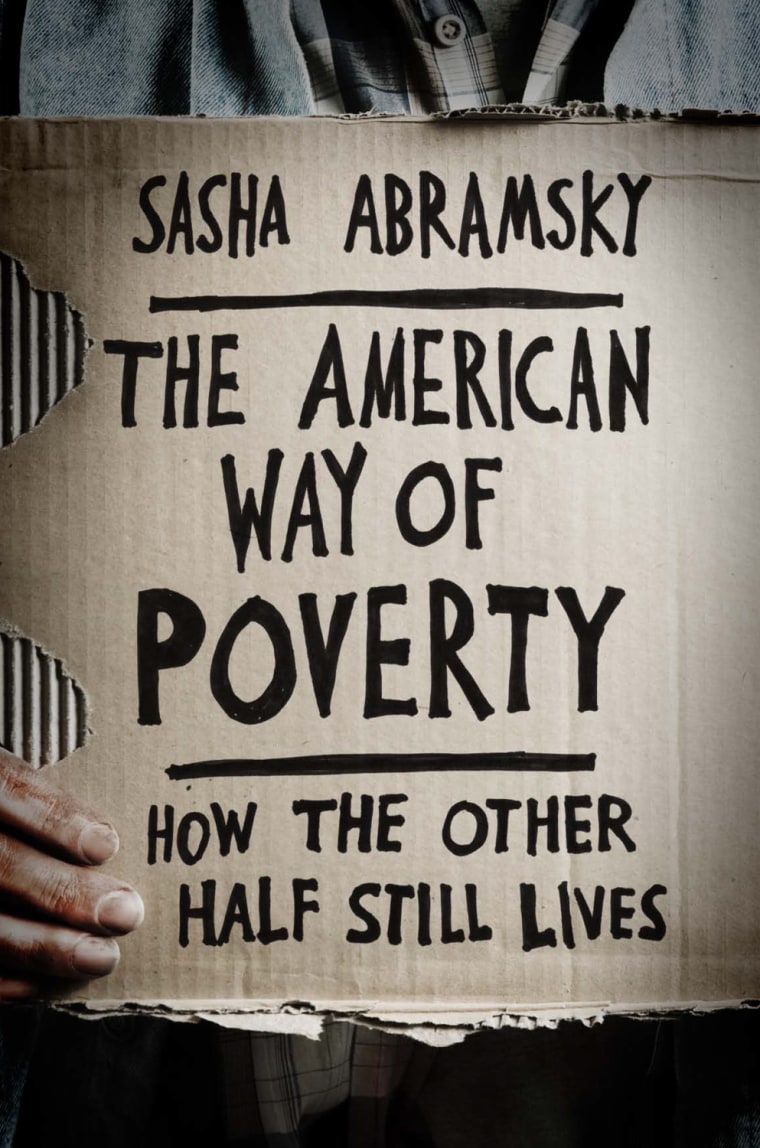

Abramsky traveled across this country, and interviewed hundreds of people, both the newly poor and the long-term poor, for his book, The American Way of Poverty: How the Other Half Still Lives. Abramsky’s project comes 50 years after Michael Harrington’s groundbreaking 1962 report on poverty, The Other America. Like Harrington, Abramsky wants to grab America by the throat and say, “look!,” and also, “do something!”

Abramsky lays out his own blueprint for action; he wants a new “war on poverty:” what he calls a public works fund to protect against mass unemployment; an educational opportunity fund to expand access to and affordability of higher education; a poverty-mitigation fund; and money to stabilize Social Security and reduce the deficit, made possible by higher taxes on the wealthy.

Abramsky spoke with NBC News.

NBC News: Over 50 years ago, Michael Harrington warned that unless attention was paid, and something was done, somebody in a future generation would write another book about “the other America,” and it would be the same story, or worse. Are you that somebody Harrington was talking about, and is it indeed the same story, or worse?

Abramsky: Certainly Harrington was the inspiration for what I was doing. It’s the same in some ways, it’s different in other ways. One of the things the war on poverty was most successful at was massively reducing the poverty of the elderly. And that’s still the case. A far lower percentage of America’s elderly today are poor [as a result]. We’ve done a less good job eliminating child poverty. A lot of the conditions for kids I talked to would be very familiar to Harrington. And the geographic areas he wrote about – inner city slums, Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta – those areas still are very poor.

On the other hand, one of the things Harrington wouldn’t have found that anybody writing about poverty today does find is suburban poverty, people who on the surface have it all – they have these big houses, these big cars, swimming pools – but it’s a charade, because they’re under water on their mortgages, a lot of them are out of work, their economic security has disappeared, they’ve got huge amounts of debt, and a lot of them end up on food lines. Harrington wouldn’t have seen the suburbanization of skid row.

Why do you think poverty is so invisible, even though it is often right in plain sight?

The lives the poor live are so separate from the more affluent, that it’s possible to pretend it’s not happening. Poor people increasingly seal themselves off because they can’t afford to participate in communal rites. They can’t have coffee with friends, they can’t go out to movies, they can’t go out to restaurants, so increasingly their lives are less public. Often, poor people live in out-of-the-way neighborhoods, like trailer parks on the side of a highway. You speed past that, and if you don’t live in that trailer park or know someone who lives there, you’re not going to stop.

You have said that America’s political leaders ignore poverty that is staring them in the face, that they willfully turn a blind eye, and that there is an affirmative desire for poverty as a mechanism of social control. That’s quite an indictment.

I’m not sure I said it quite like that, but we have created a system that disproportionately benefits a very small group of people. And I do think parts of the political process do benefit from poor people not voting, and from a sense of poor people’s disempowerment. There’s a neglect that slides to being a malign neglect. At a certain point it’s not just ignoring the problem, it’s creating the policies that make that problem worse. And I do think they benefit from the political narrative that blames the poor for being poor. If you can say a poor person is hungry and homeless because they’ve done something wrong, they’re somehow not quite up to par, then your failure as a political leader to step in and work out ways to solve those problems is no longer your failure.

NBC News recently talked to Congressman Paul Ryan about the “war on poverty.” And he told us it’s been a dismal failure. He thinks the American safety net traps people in poverty by creating disincentives for them to do the things that might change their lives. What’s your reaction to that?

The American safety net has many imperfections. You can find instances where poverty traps have been created. But to say the problem with poverty is that the government is making matters worse, is just not true. Poor people work incredibly hard, some work two and three jobs. But they don’t have the right skills to get high wages. You find people who are desperate to get work but there is no work. It’s too easy when powerful people blame poor people for being poor. And it does nothing to solve the problem.

You have traveled thousands of miles around the country—

--probably tens of thousands!

--to see what poverty looks like, and how the other half still lives. What might surprise people about what poverty today looks like?

It’s the degree to which insecurity has become a daily reality for tens of millions of people.

As you acknowledge, poverty is expensive to fix. The solutions you suggest in the second half of your book cost a lot of money. In a time when a lot of people feel they don’t have what they need, when many are saying, we’ve tried that approach and it didn’t work – how realistic is a framework that costs a lot of money?

It’s unrealistic as long as there’s zero trust in government, because why would you throw good money after bad? But if you can create a couple of programs that really work, and show people they get bang for the buck, you start changing things so that people don’t think, ‘nothing government does ever works.’ And then you can start to have the broader conversation about what a new ‘war on poverty’ might look like. You also need political leadership to take a stand. Nothing I propose will go anywhere unless you have senior political figures willing to declare poverty a massive national crisis.

You write that you’ve been struck by the tremendous resilience of poor people despite all the obstacles in their path.

I talked to a young woman in Idaho. She’d been a teenage drug addict, and she’d had an abusive relationship with a man for several years. Everything had gone wrong for her, but she’d found a way through. She got off drugs, was in a better relationship, and she was now working. Her life was on an upward trajectory.

A lot of people I talked to had gone through personal problems, or been on the wrong side of the economic collapse, and they were doing a lot of things to get their lives back on track. They weren’t waiting around for other people to take the initiative. They were pushing against the odds.

Editor’s note: this interview has been edited and condensed.

Related content:

What poverty in America looks like

The great disconnect: Five years after Lehman