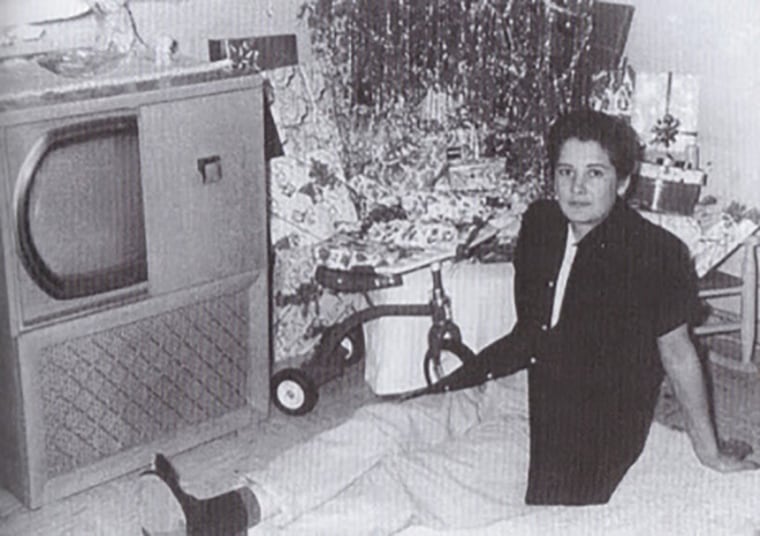

Retired barber Nancy Valverde still suffers back pain after reportedly being assaulted by a Los Angeles police officer in the late 1950s. She said the officer kicked her in the back after a routine arrest for wearing men’s clothes.

“I was in the elevator, I was handcuffed,” the 84-year-old lesbian told NBC OUT. She recalled that in the those days “they used to handcuff you in the front.”

“The two cops were behind me, and they were going to book me over at the city jail, and they were talking back and forth like, ‘Well, she thinks she’s this, she thinks she’s that. She better not mess around with my wife…’ Just being nasty. And when the door opened they kicked my back,” she said.

Valverde alleged the police in her East Los Angeles neighborhood routinely arrested her for a crime then known as “masquerading,” a law that criminalized women for wearing men’s clothes and vice versa.

“I don’t know maybe I was stubborn, or stupid, I don’t know. But I couldn’t see myself wearing those female clothing, you know. I was not comfortable,” Valverde said.

Valverde liked to look dapper when she was young. She purchased men’s slacks and button down shirts and got them tailored to fit her slender frame.

“I knew I was different, but there was nobody to relate to. No role models, no nothing. Although I saw other women—tomboys. But in those years everyone was afraid to come out. I felt alone out there, you know, and I got arrested,” Valverde said.

Valverde was in barber school at the time.She said that every day when she left class, a police car would be waiting for her outside the school. If she saw a police officer on the street, she would run into a doorway and hide to avoid arrest. She said that after years of going to jail over the way she dressed, she had enough.

“I just couldn’t take it anymore,” she said.

Valverde went to the law library and looked up the masquerading law. She found a similar case from 1950 where the California Supreme Court ruled that wearing clothing of the opposite sex was not a crime. She decided to hire a lawyer.

“We went to court, and that was the last time I was arrest[ed],” she explained.

She soon graduated from barber school and opened her own shop. Severe back pain from being kicked forced her to give up barbering after 25 years. She said her body still tightens up when she sees a police officer.

“I used to call myself a victim, now I call myself a survivor,” Valverde said.

“You know, I was very lucky. I’m 84 years-old now, and I think, ‘My gosh, what did I live through?’… I don’t know what it was. I just lived through it,” she said.

Valverde is one of many ordinary LGBTQ citizens who started to take a stand against police harassment in the 1950s and 60s, according to historian Lillian Faderman, who wrote about Valverde in her book “Gay L.A.”

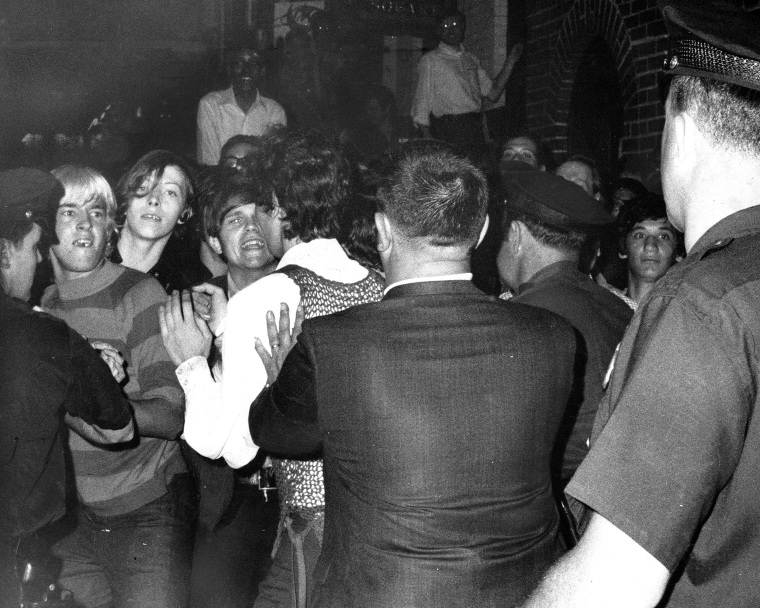

“In the 50s there just weren’t enough of us that were willing to come out and say ‘I’m a homosexual, and you can’t do this to me, you can’t do this to my community.’ There were individuals who might protest, but there was no organized group that had very much power,” Faderman said. She added that masquerading laws existed in most big cities, and that anti-sodomy and entrapment laws were also used to persecute the community. Police raids on gay bars were common, she added.

But as ordinary citizens like Valverde started to fight back and win their cases, a gradual shift took place, Faderman explained. Not long after the legendary 1969 Stonewall riots, mainstream LGBTQ advocacy organizations like the National LGBTQ Task Force (then known as the National Gay Task Force) and the Lambda Legal Defense Fund formed in 1973. The Gay Rights National Lobby, a Washington D.C.-based gay rights advocacy organization, formed a year later.

“Those were mainstreaming organizations made up of middle and upper middle class gays and lesbians who figured out that you could fight, you could challenge the laws in a united kind of way,” Faderman said. In the 1970s, sodomy laws were repealed in 19 states. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled existing sodomy laws unconstitutional in 2003.

“More people [were] coming out of the closet,” Faderman said. “More and more people [were] willing to join organizations that would fight those laws.”

Law enforcement agencies have since taken steps to improve their relationship with the LGBTQ community. Some agencies, like the New York City Police Department, have formed LGBTQ liaison units to aid the process—and even march in their city’s Pride parade. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, which Faderman said was implicit in persecuting LGBTQ groups and individuals in federal employment during the 1950s, is also transforming. The agency recently created a program tasked with recruiting and retaining LGBTQ talent as part of a larger diversity initiative.

“This is not the FBI of the 1950s,” said FBI Inspector Vadim Thomas, a champion of the program. “We have a new director. We’re changing our culture, and we want members of the LGBT community among us. We welcome them. We want their talent. We want their drive. We want those individuals. It’s the right thing to do for us. It’s the right thing to do for the United States.”

Thomas said the FBI has learned lessons from other law enforcement agencies that have been progressive in embracing the LGBTQ community.

“We’ve gone to them. We’ve asked them for advice. We’ve seen what they do well, and we didn’t need to recreate the wheel. We adopted those ways and refined them a little bit to see what we need to do, but we’ve learned a lot from other law enforcement organizations,” he said.

While many law enforcement agencies have evolved since Valverde’s time, studies show the relationship between law enforcement and the LGBTQ community continues to have its problems. Nearly 50 percent of LGBTQ victims of violence surveyed in 2013 reported experiencing police misconduct, according to a Williams Institute report. In a separate study from the the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 25 percent of LGBTQ survivors of intimate partner violence reported experiencing interactions with police that were either indifferent or hostile.

A big part of the problem is that discrimination still impacts the community, particularly transgender and LGBTQ people of color, according to Meghan Maury, Criminal and Economic Justice Project Director for the National LGBTQ Task Force.

“I think racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia are still pretty ubiquitous in this country,” Maury said. “We’ve made progress, but that’s something that’s not gone away particularly.”

Maury said she has been on “quite a few ride-alongs with law enforcement officers,” and has witnessed some of their interactions first hand.

“When [police] role up and stop a trans woman on the street, it’s often because they’re profiling her as a sex worker because she’s trans, but the interaction between them is informed both by the fact that she’s a black trans woman and by the fact that they think she’s probably on drugs and probably engaged in some other kind of street crime,” Maury said.

She said laws that criminalize sex work, homelessness, drug use and HIV, which all disproportionately affect the LGBTQ community, exacerbate the problem. “Even though law enforcement agencies are looking to do well, they’re still going to struggle because of the criminalization they’re tasked with enforcing,” Maury noted.

She said increasing diversity within police departments can help improve interactions with the communities they serve. The U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission released a report in October that highlights practices to assist them. But even progressive agencies can harbor prejudice, Maury noted. The San Francisco Police Department — an agency long-touted for its diversity — found itself at the center of controversy this year when some of its officers allegedly exchanged racist and homophobic text messages.

“There’s a lot of relationship development that needs to happen with law enforcement to get them to understand and adopt different policies and procedures, but that relationship development is really difficult when you’re talking about a community that already has strained relations with the law enforcement department,” Maury said.

“Until there’s [a] cultural shift in the agency, you’re not going to get effective change from that agency,” she said.

Nancy Valverde is the subject of an in-progress documentary "L.A. Queer History." Learn more about her story here.