In 1963, an Estonian war hero, family man and chairman of a Soviet collective farm was arrested on suspicion of homosexuality. He escaped court conviction, thanks to his solid Communist Party position, but he was summarily fired and expelled from the party, and his marriage was dissolved. He was soon arrested again on the same charge, and this time, powerless, he was sentenced to a year and half of hard labor. A broken ex-con, he spent the 1970s and 1980s living quietly and cruising heavily in Tartu, Estonia's second biggest city. In 1991 — the very year Estonia finally reclaimed formal independence from the Soviet Union — he was found murdered in his home, allegedly by a male prostitute.

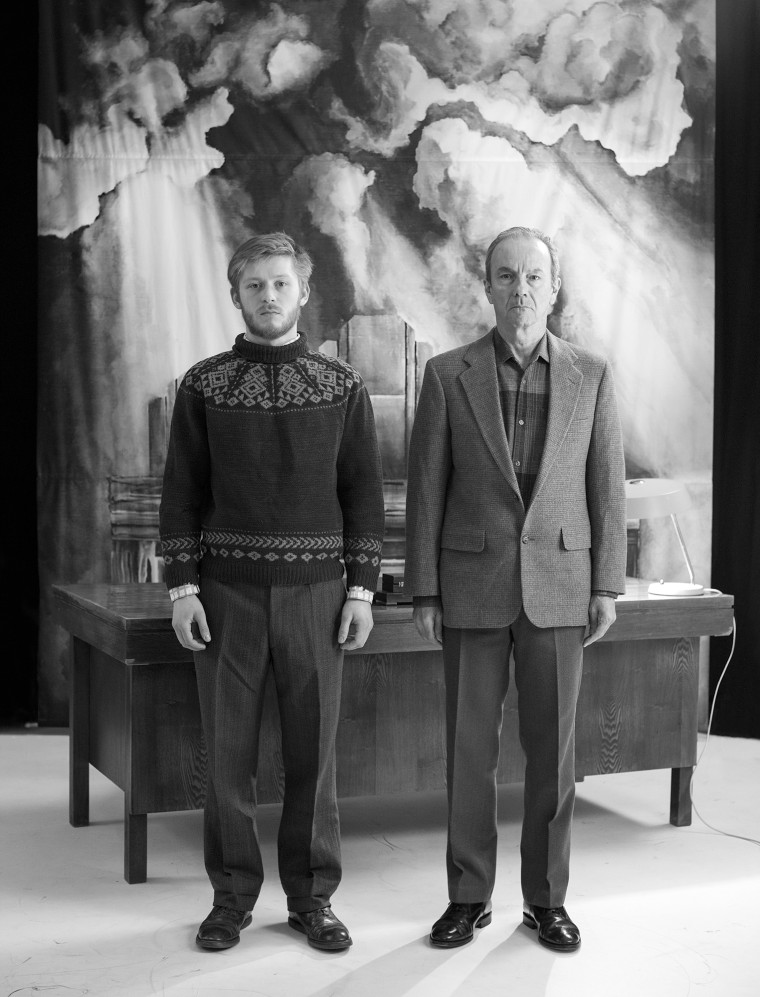

Now, a quarter century later, the chairman's tragic story fittingly serves as the inspiration for a bold art exhibition at Estonia's Museum of Occupations in Tallinn, a sober but fascinating memorial to the country's years under Soviet (and briefly Nazi) subjugation from 1940 to 1991. Called "NSFW: A Chairman's Tale," the multimedia installation by openly gay young Estonian artist Jaanus Samma, which was also chosen to represent Estonia at the Venice Biennale in 2015, is strikingly candid and graphic. It's a powerful testament to how far things have come for LGBTQ people in Estonia since the chairman's days, especially given the unrelenting anti-gay climate in Estonia's big and looming next door neighbor, Russia.

"It's a very interesting experience doing this show in the Museum of Occupations, because it's not a traditional art space," Samma told NBC OUT. "If a person goes to a gallery or an art museum, one is prepared to see something that has many ways of interpreting or looking at. But in a history museum, one expects to see facts and documents, and there is no space for open concepts. But since this show tells a story of a man who lived in Soviet Estonia, it fits perfectly in the context of the Museum of Occupations. Estonians are used to talking about Soviet occupation in very stereotypical terms, and I think the exhibition gives it another perspective, because it is about things that have been untold, unwritten and deliberately forgotten."

Living conditions for LGBTQ people in Estonia and its Baltic State sisters, Latvia and Lithuania, have been slowly improving since the countries each reclaimed full independence with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early '90s. By all accounts change has come faster in Estonia — which has even passed, if not yet fully implemented, a registered partnership law — than in the other two Baltics, which still have some of Europe's poorest records in terms of LGBTQ rights, according to ILGA's latest Rainbow Europe Index.

"Estonia has always been a little different," Kristine Garina, chair of Mozaika, Latvia's LGBTQ rights and advocacy organization, said. "Even in Soviet times, I think Estonian society wasn't screwed up as badly as we were in the rest of the Soviet Republics. I suspect it has to do with Estonia being so close to Finland — geographically, mentally and language-and culture-wise — that it was always closer to Scandinavia than the Baltics anyway. When people think of the Baltic States, they think of three similar countries, but Estonia is miles ahead of us in Lithuania and Latvia. In Estonia, politicians never used homophobia as their only political platform, at least not as strongly as here. In Latvia, from 2005 to 2007 there were whole political movements that built their success only on open homophobia, and they are largely responsible for the extremely slow progress — and even regress — of LGBT rights here."

"In the Baltics, we live in a kind of limbo situation," filmmaker Romas Zabarauskas said. His latest feature, You Can't Escape Lithuania — a fictionalized version of his own life as an out gay Lithuanian director — will have its world premiere at New York's Bushwick Film Festival on Friday (his success comes on the heels of that of Lithuanian-born director Alanté Kavaïté, whose lesbian romance, "The Summer of Sangailė," a hit at numerous international film festivals in 2015, is currently streaming on Netflix). "LGBT+ people are mistreated [in the Baltics]," Zabarauskas added, "but at the same time we do have major non-discrimination laws passed to fit in the European Union. Many people are satisfied with this limited sense of security and fail to see a bigger picture."

Fortunately, some, including key politicians, do see a bigger picture. Latvian Foreign Minister Edgars Rinkēvičs stunned nearly everyone when he came out publicly on Twitter in 2014, something Garina said was a milestone event. "Considering we still have just a handful of out LGBT people, everyone counts — but especially someone at such a high position," she said. "He took some criticism, there was a little drama at the time, but eventually he proved that it didn't matter to his career or his ability to do his job. The most common question or comment you'd hear from people is why they needed to know that about him. He's still a respected politician, and that's exactly the kind of example that the LGBT community needs."

Next door in Estonia, Parliament Member Imre Sooäär took the brave and politically risky step of co-authoring the country's Civil Partnership Act, which was narrowly passed on its third reading in 2014 and officially came into law on January 1 of this year (though subsequent implementation acts necessary for it to be carried out have yet to be approved). "It was extremely difficult," Sooäär said of the long road to getting the legislation passed. "The main difficulty was to overcome the pressures and notions of Soviet occupation, which have left society emotionally crippled. In the Soviet Union, same-sex relationships were criminalized, and the older generation still has the feeling that it is something criminal and sick. It takes a generation to overcome these notions."

Indeed, Soviet occupation also brought decades of Russian settlers to Estonia and Latvia (and to a lesser extent, Lithuania), whose descendants stayed on in the Baltics after the small countries gained independence in the early '90s but have largely remained cloistered within Russian-speaking — and Russian-thinking — communities ever since. In both Estonia and Latvia, ethnic Russians still make up about a quarter of the population. "Public opinion surveys show that ethnic Russians are becoming less and less tolerant," Helen Talalaev, a board member of the Estonian LGBT Association, said. "This is probably due to the fact that many Russian-speaking people use Russian media a lot, and hence they get the anti-propaganda agenda from there."

Garina said the situation is similar in Latvia. "I hate to generalize and call the Russian-speaking part of society more homophobic than the rest," she cautioned. "That is of course a huge generalization, and there’s plenty of homophobes amongst ethnic Latvians as well. But the fact is, sadly, the Russian-speaking community is largely living in Russia's media space — which is still freely available in Latvia — and the overwhelming propaganda machine is, of course, working. We’ve witnessed a lot more aggression and anger from the Russian-speaking part of the society in terms of LGBT rights."

Whether due to populace or proximity, the Russian effect has even spilled over into Baltic politics. Anti-gay Lithuanian lawmakers are attempting to add a Russia-like "gay propaganda" law to its Code of Administrative Violations, and though the bill was tabled last November, it could be resubmitted at any time. Garina thinks it's within the realm of possibility that something similar could happen in Latvia. "Luckily though, laws can be repealed, and I'm sure it wouldn’t last long," she said. "As a society we've lived in this horrible censorship state for 50 years, so I hope we're smarter than that."

If enacted, Lithuania's gay propaganda law could forbid Pride marches, which would preclude it from hosting further editions of Baltic Pride, as it did in Vilnius, the country's capital, in June. Since 2009, the three Baltic States have taken turns hosting the event, which in 2015 took on even wider significance in Riga, Latvia's capital, when it expanded to become EuroPride. "I'd like to think it was probably the most important EuroPride ever," Garina said. "But it mostly changed the LGBT community itself, not how people perceive it. I think it was incredibly important to see how many people — lots of them straight allies — came out on the streets to support LGBT rights. It was an incredible confidence boost to LGBT people here."

As Samma's exhibition proves, art can also help boost confidence and change public perceptions, even when said art includes graphic imagery. "We shouldn’t censor ourselves and think too strategically what would be the best way of showing queer people," Samma said. "I believe we should show life in its full complexity and without underestimating the audience."

For his part, Zabarauskas has teamed up with local Vilnius photographer Arcana Femina to create the just-released profile collection "Lithuania Comes Out: 99 LGBT+ Stories." "For this book, I talked with people from small villages as well as big cities, from an electrician to a political scientist, from poor to rich," he said. "Some young people are being thrown out of their homes and beaten, others enjoy a comfortable life with accepting parents. But that doesn't change the fact that all LGBT+ people are considered second class citizens by our state."

"It's often said that things will get better over time," Zabarauskas added. "But this is complete nonsense. Nothing ever changes with time. It's only we as active citizens who can change things ourselves."

Romas Zabarauskas's "You Can't Escape Lithuania" will have its world premiere at the Bushwick Film Festival on September 30. Jaanus Samma's "NSFW: A Chairman's Tale" will be on display at Tallinn's Museum of Occupations through October 15.