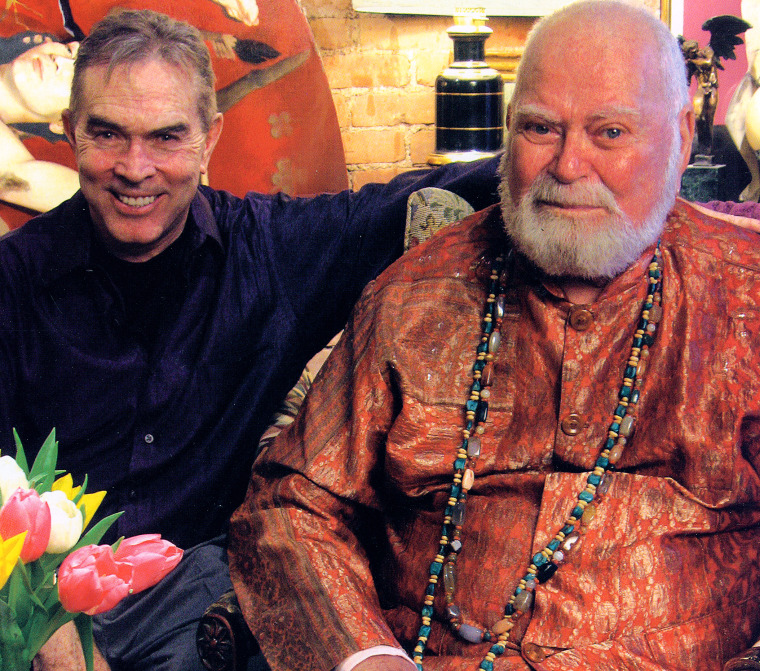

When New York City art collectors Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman were introduced at a brunch in the early 1960s, they were instantly attracted to each other.

“As the French say, it was a coup de foudre — lightning struck,” Leslie told NBC Out.

The attraction was purely physical at first, according to Leslie, then a 29-year-old performing artist from South Dakota. Lohman, an interior designer 11 years Leslie’s senior, had all the qualities he longed for in a lover: handsome, sophisticated, erudite and urbane.

The men quickly fell in love over their mutual passion for homoerotic art. Together they would co-found the Leslie-Lohman Gay and Lesbian Art Museum, the world’s first museum dedicated to gay and lesbian art, according to its website.

“One of our great bonds was wherever we traveled — we traveled a great deal — was collecting work and hunting for work,” said Leslie, now 84 years old. “It’s amazing the amount we found stashed away in the back of stores and galleries and whatnot.”

Related: This Year's 10 Must-See LGBTQ Art Shows

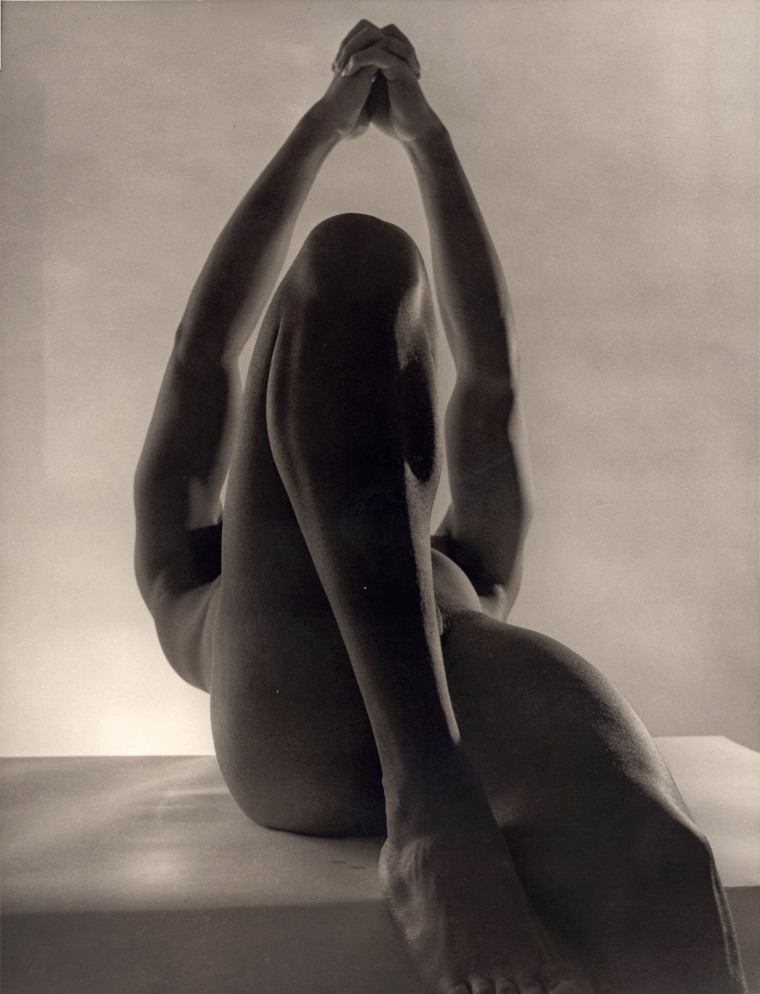

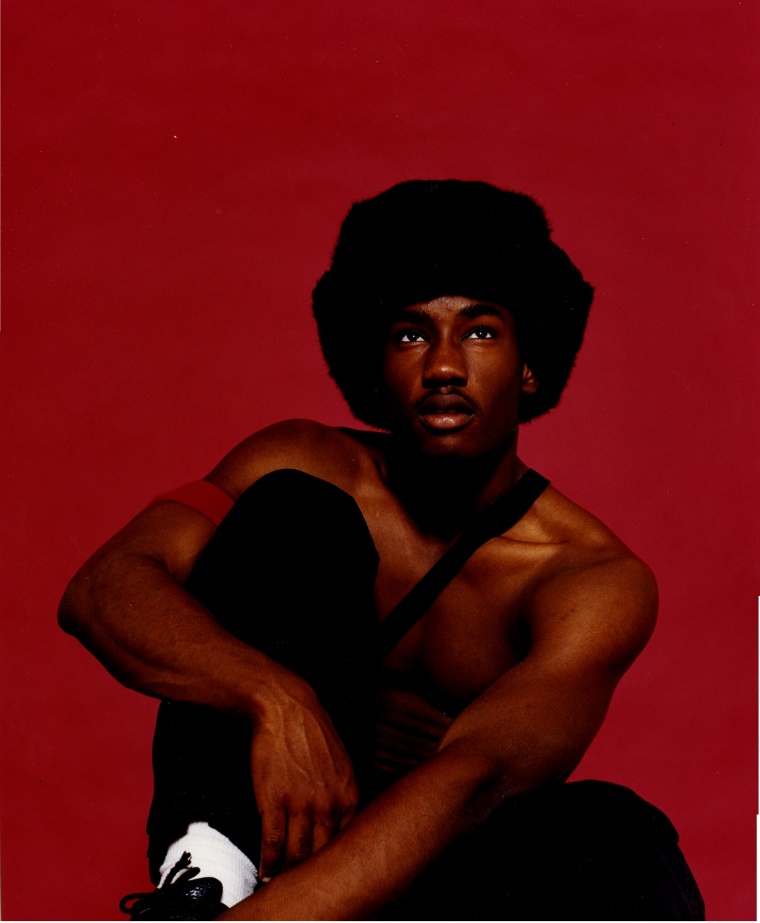

The men spent 50 years traveling the world in search of gay art. Much of what they found had been denied a presence in mainstream art venues — some of it homoerotic, some of it romantic, and some of it political, according to Leslie. He said gay artists typically created art for each other.

“It was kind of a friendly thing to do — draw an erotic piece or paint an erotic piece and give it to a friend,” Leslie explained. Artwork that was explicitly homoerotic was typically kept secret, he explained.

“Gay people have historically been denied the experience of seeing themselves in popular culture, so it’s always hidden,” he said. “And we felt that the time for that was over.”

In June 1969 — coincidentally, the same month of the New York City Stonewall Riots — the pair opened a small art studio in Manhattan dedicated to gay artists. A one-weekend art show attracted more than 300 people to its opening, Leslie said. But it would be decades before the collection would find acceptance within mainstream society. From federal officials who scoffed at their early attempts to apply for nonprofit status, to a knife-wielding vandal who slashed several paintings, the gallery had its setbacks, according to Leslie.

“Someone suggested we drop the word ‘gay’ out of [our name]. Instead of the ‘Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation,’ just call it the Leslie-Lohman Art Foundation. And I said, ‘That would be burying the whole point. I don’t want people to think it’s just another art foundation — I want them to know what it’s about,’” he explained.

With the help of a tenacious lawyer, the gallery was granted non-profit status in 1987. It was the height of the AIDS crisis, when many gay artists were dying. Family members would often destroy their artwork, Leslie said.

“We had a young architect from California who we knew and had a really excellent collection with several pieces of sculpture in it. Fritz and I stopped to see the collection on our way to Japan once,” Leslie said. A year later, a friend of the architect called them in desperation. The architect had passed away from AIDS complications, the friend said, and his mother and a priest were outside his apartment throwing his collection into a dumpster.

“There was nothing we could do,” Leslie said, exasperated. “The collection was destroyed.”

Leslie and Lohman did save many works from artists and collectors who died during the epidemic, however, including paintings from Robert Bliss, an artist who drew “tender and beautiful paintings of late [male] adolescence,” according to Leslie. They also saved works from lesser-known artists.

“We had one young artist from Alabama or some such place. Beautiful artist and his work was beautiful — almost Japanese it was so gorgeous, and it involved some male nudity,” Leslie said. After the artist died, Leslie called his mother to tell her he had her son’s drawings left over from an art show.

“Her answer was, ‘Well, I don’t know why he wanted to draw them terrible pictures.’ And I said, ‘Well, you know, we are responsible for them now, and if we can sell any, the money goes to you.’ Pause. Silence. And she said ‘How much?’ And I thought, ‘This tells us who they really are,’” Leslie said.

He said many artists and collectors who died during the AIDS epidemic were their close friends.

“We were constantly at bedsides and memorials,” Leslie said. “It felt like it was just never going to end.” One of their closest friends who died was artist George Dudley.

“He said, ‘Just promise me one thing, you’ll take care of my art.’ And of course, we have it. It’s part of the permanent collection,” Leslie said.

Leslie said the couple’s collection includes works from gay artists like Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe and George Platt Lynes. He said they also collected works from lesbian and transgender artists, including Marion Pinto and Cupid Ojala.

One of Leslie’s most favorite pieces is Marion Pinto’s “Sleeping Church Nude.” “It’s a beautiful picture of a glowing interior of a cathedral, and in the foreground is a beautiful nude woman stretched out before the alter,” he said.

A nude dual portrait of the couple lying side by side — also by Marion Pinto — hangs above Leslie’s couch in his apartment. It was Lohman’s favorite piece, according to Leslie. Lohman died from cardiac arrest in 2009.

“I was absolutely adrift for a year,” Leslie said about Lohman’s death. “I could barely function for a while. But you know, life goes on.”

The foundation officially became a museum in 2011, according to its website. It reopened in March after a major expansion, and contains a collection of over 30,000 objects. It’s become increasingly popular with the public, Leslie said.

“More and more straight people are visiting the museum, which I find wonderful,” he added.

The museum’s latest exhibit, “Expanded Visions: Fifty Years of Collecting,” includes 250 works from the Leslie-Lohman collection. It explores the evolution of the museum amid decades of shifting social conditions, according to its website.

"Expanded Visions: Fifty Years of Collecting" will be on display at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York City until May 21.