Even the greatest among us can stumble.

As the world mourns the passing of Nelson Mandela, it is important to look at the one area where the iconic former president of South Africa slipped — AIDS. The most outstanding moral figure of our age did not do what was needed as HIV began to destroy the country he loved. But his actions after he realized his failures are an important part of his legacy.

South Africa is beset with the worst epidemic of HIV in the world. According to the United Nations, out of a South African population of just over 51 million, 6.1 million of its citizens were infected with HIV in 2012, including 410,000 children under the age of 14. An estimated 240,000 South Africans died in 2012 from AIDS. There are 2.5 million children orphaned because of the disease. The grim social, economic and medical toll AIDS has exacted on Mandela’s country is almost beyond description.

In 1990, when Mandela was released from a 27-year prison sentence, the rate of HIV infection among adult South Africans was less than 1 percent. When the anti-apartheid activist was elected president four years later, AIDS was on it way to being an out-of-control plague, with infection rates doubling every year. In 1998, the rate of HIV infection among adults in South Africa was almost 13 percent, with 2.9 million people HIV positive.

Mandela and his party were more or less indifferent to AIDS throughout his five-year tenure. There were other huge challenges in rebuilding the new post-apartheid nation — but the indifference was not just a matter of priorities. Mandela and his party did not want to admit they had a problem.

Why they did not take prompt action to slow the epidemic's spread is not clear. Perhaps Mandela and his people — like United States President Ronald Reagan and his administration in the 1980s — found the disease and its modes of transmission too repellent to acknowledge. Maybe they did not want to tarnish the new state with a problem that at the time carried so much stigma and shame.

The failure to take on AIDS was made worse by Mandela’s hand-picked successor for the presidency, Thabo Mbeki, who took office in 1999. Mbeki announced repeatedly throughout the late 1990s that AIDS was not fatal, that HIV did not cause AIDS, that home brew treatments could cure AIDS and that life-saving antiretroviral drugs were being promoted so the West could profit at South Africa’s expense. The government did nothing to buy drugs that might have prevented mother-to-child transmission.

Through all this Mandela was more or less silent.

By the early 2000s, it was obvious that AIDS denialism was putting the entire nation at risk. Other African and Asian nations, which followed aggressive safe-sex and drug treatment programs, were doing much better than South Africa. Europe, Australia and the U.S. were getting a handle on the plague as well.

The message was not lost on Mandela. It had been an enormous mistake to ignore the epidemic, made even worse by installing an AIDS denialist as his favored successor.

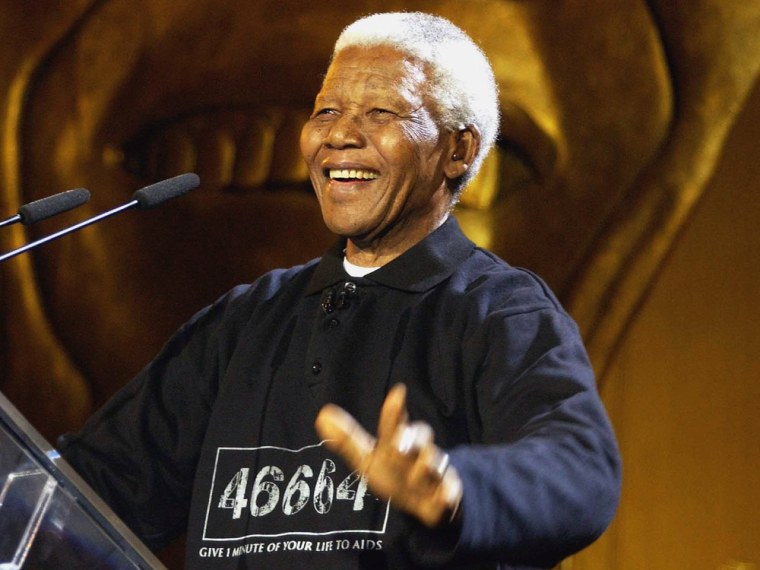

In 2003 Mandela began to speak out plainly and forcefully about AIDS. And he acted. He created a foundation to fight HIV/AIDS, the Nelson Mandela Foundation, and began a fundraising campaign to support HIV prevention and public health efforts called 46664, his identification number when he was imprisoned by the apartheid government on Robben Island. For the rest of his life he urged people to talk about HIV/AIDS "to make it appear like a normal illness.” And he used his reputation to make HIV prevention and AIDS treatment an international issue. In his retirement, he put AIDS at the top of his personal agenda.

And then Mandela personally experienced the horrible price of his early stumble against AIDS.

On Jan. 6, 2005, Mandela shocked the world when he summoned the media to his Johannesburg residence to announce his sole surviving son, Makgatho, 54, had died that morning. Mandela was forthright about the cause: “My son has died from AIDS.”

Mandela vigorously took on critics, speaking courageously about AIDS and the importance of using the best science and public health knowledge to defeat it. Our greatest ethical leaders like Mandela are never more instructive than when we learn not just from their triumphs, but also from how they recognize and respond to a mistake.

Arthur Caplan is the head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center.