Vaccinating teenage boys against the human papillomavirus (HPV) could save millions of health care dollars by preventing head and neck cancer, according to new research.

Most know of HPV as the sexually transmitted virus that causes cervical cancer and genital warts, but it has been linked to a number of other cancers, including anal, vulvar and oropharyngeal cancer, which occurs in the throat, around the tonsils and back of the tongue.

Prior to the 1990s it was thought that head and neck cancers were primarily caused by smoking and drinking, but over the past 30 years there has been a sharp spike in these cancers in heterosexual males, leading experts to look for another explanation.

Dr. Maura Gillison, professor of medicine at The Ohio State University, was one of the first to discover that HPV could cause cancers of the head and neck. She attributes the increase to “changes in sexual behaviors that started in the 1930s and accelerated in the 1960s-70s that largely affected the number of partners one had in their lifetime.”

Currently, it’s estimated that 70 percent of all head and neck cancers are caused by HPV, likely spread by oral sex. According to experts, by 2020 oropharyngeal will beat out cervical cancer as the most common HPV-related cancer.

"There is a strong gender difference," says Gillison — men are at a three to five fold increased risk compared to women. It gained national attention in 2013 when actor Michael Douglas announced that he was being treated for throat cancer, likely caused by HPV.

In the new study, published in CANCER, the journal of the American Cancer Society, researchers applied a statistical model to over 190,000 Canadian boys who were 12 in 2012, and found that vaccination could save anywhere from $8 to $28 million Canadian dollars over the boys’ lifespan, depending on the efficacy of the vaccine and how many boys actually got vaccinated.

“We understand a model is just a model, so there are limitations, but our goal was to raise awareness and discussion,” said Dr. Lillian Siu, study author and senior medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Center.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted disease in the U.S. Experts estimate that over 80 percent of sexually active people will become infected, and the virus is often asymptomatic, meaning many spread the virus without even knowing they’re infected.

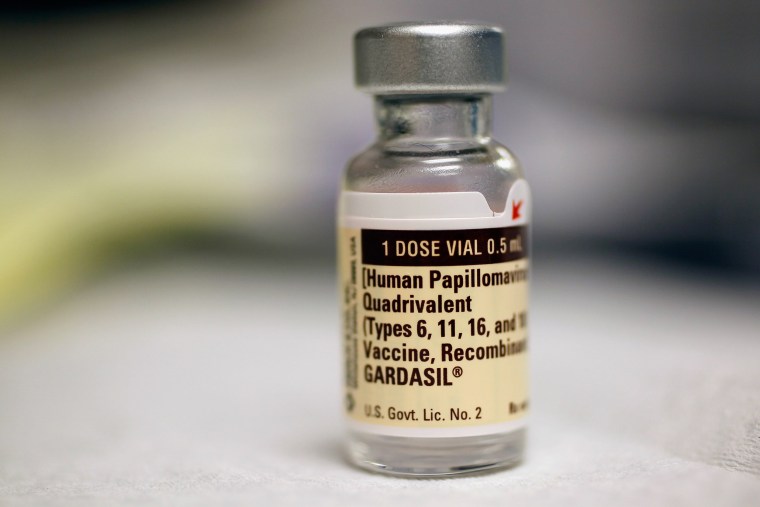

There are over 100 types of HPV, at least 13 of which are cancer causing. The FDA approved vaccines—Cervarix and Gardasil — both cover strains 16 and 18, responsible for 70 percent of cervical cancers. Gardasil additionally covers the wart-causing strains 6 and 11. A new form of Gardasil, approved earlier this year, adds five new high-risk HPV strains to its coverage, for even more cancer protection.

The CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend both boys and girls get the three-part vaccine at age 11-12, although it is approved for ages 9-26. For HPV vaccines to work, they should be administered before a person is exposed to HPV, the CDC says. That's why there's been a push for younger people to get vaccinated.

Despite this recommendation and numerous public health campaigns, there has been poor uptake in the U.S—only 38 percent of girls and 14 percent of boys had been fully vaccinated in 2013. Much of the opposition to the vaccine has centered around the fear that protecting young children against HPV could lead them to experiment with sex.

“We have to stop thinking about the STD…It is a cancer vaccine and people need to be referring to it as a cancer vaccine,” says Electra Paskett, co-leader of the cancer control research program at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. Paskett notes that in countries like Australia where cancer protection was emphasized, vaccination rates are upwards of 80 percent.

While still a champion of the cancer-fighting vaccine, Gillison raises some concern over the findings of this study, which are based on hypothetical efficacy rates, because while the HPV vaccine has repeatedly been shown to be highly effective at preventing cervical and genital cancers, there has never been a large, high quality study to prove that HPV vaccines can prevent cancer-causing oral infections. “The standard is to have clear evidence of efficacy from a prospective clinical trial,” says Gillison.

Siu argues the study still has meaning.

“As a medical oncologist who sees the disease at the end of the spectrum, our question always is: Are there ways to prevent it? There is a vaccine out there and it’s something we should look into. We can’t always wait for randomized data," Siu said.

So what’s the take away?

While it’s unlikely that the HPV vaccine will be marketed as the “oral cancer” vaccine without further research, the fact remains that it already offers protection against cervical cancer, genital cancers and warts. And if there’s a chance that it protects against head and neck cancers too, “that’s a pretty amazing secondary benefit,” says Gillison.