The Youngstown, Ohio, baby turned blue again and again as his little airways collapsed and kept air from reaching his lungs. But doctors used a 3-D bioprinter to custom-make a splint that is holding his airway open and helping him breathe.

Now 19-month-old Kaiba Gionfriddo is “into everything”, says his mother, April Gionfriddo.

"Quite a few doctors said he had a good chance of not leaving the hospital alive," she adds.

Kaiba’s life was saved by a brand-new field of regenerative medicine based on plastics and inkjet printers. Doctors at the University of Michigan used CT scans of Kaiba’s little airways to custom-design a scaffolding to pull open the passages and hold them open until they could grow strong and healthy on their own.

Kaiba was born with a rare condition called tracheobronchomalacia. This deformity affects about one in 2,200 babies and causes the airways to be weak and prone to collapse. In tiny babies, it can look like asthma and it can take a while to diagnose.

Kaiba showed early symptoms. “At 6 weeks of age, he had chest-wall retractions and difficulty feeding,” the researchers wrote in this week’s issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. April Gionfriddo says it wasn’t immediately clear what was wrong, until one morning the family was eating out when Kaiba was 2 months old.

“We went to the Waffle House,” she said in a telephone interview. “He ended up turning blue and stopped breathing on us.” They rushed to the emergency room, where doctors said the baby had just aspirated something, and sent him home.

“Two days later, he ended up turning blue on us again,” says Gionfriddo, a 32-year-old mail room worker in Youngstown, Ohio. “He ended up spending four months in the hospital.”

Kaiba needed a ventilator to breathe, and wasn’t going to be able to survive without it. Worse, he struggled and had to be sedated to tolerate the breathing tube.

“Some of the arteries, especially those coming off the aorta, are malformed,” said Scott Hollister, a professor of biomedical engineering at Michigan. “They almost form a ring around the trachea. If it’s too tight, they actually compress the airway, which happened in Kaiba’s case.”

Again and again, Kaiba’s floppy airways collapsed.

"Even with the best treatments available, he continued to have these episodes. He was imminently going to die,” said Dr. Glenn Green, a pediatric ear, nose and throat specialist at the University of Michigan “The physician treating him in Ohio knew there was no other option, other than our device in development here.”

Green had been working with Hollister to develop exactly what Kaiba needed – support for his growing bronchial tubes.

“Our laboratory has been working on this area for a long time,” Hollister said in a telephone interview. “It was a little bit intimidating as well. We had been developing the prototype and gearing it toward this application.”

Replacing the entire trachea is complex. “We felt the simplest solution was to build a device that would go around the trachea,” says Hollister.

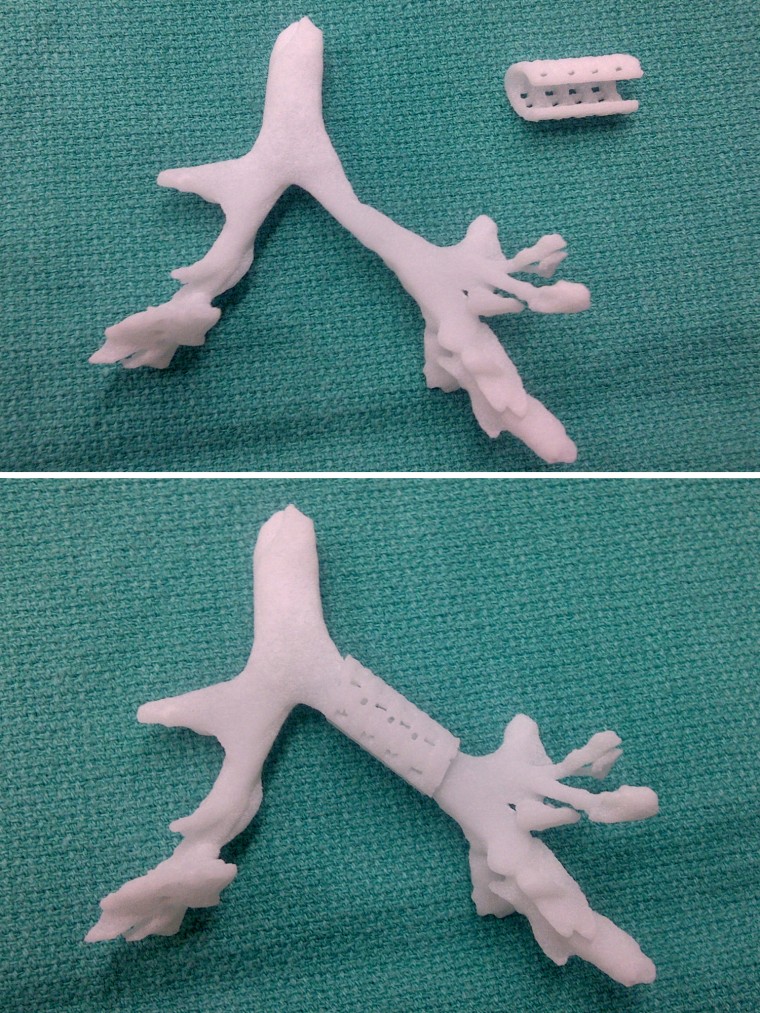

They developed a program that would design the horseshoe-shaped device, complete with small holes to allow a surgeon to suture it into place. “Then we made a model of his trachea,” says Hollister. “Just to be sure, we made it in a range of sizes.”

Hollister’s team used a bioplastic powder called polycaprolactone. “It’s a polymer that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to fill small holes in the skull,” Hollister says. The bioprinting machine melts the powder, and builds the desired shape layer by layer.

The University of Michigan team got special permission from the school’s advisory board and the FDA to go ahead. “I was a little scared at first because the doctor said he wasn’t sure it was going to work at first,” Gionfriddo says.

“But we decided to go ahead and try it. It gave him a chance. We were pretty happy they had at least something. It kind of seemed kind of cool and the other part was science fiction.”

In February of 2012, a surgical team re-arranged Kaiba’s twisted heart arteries and trachea, and then carefully placed the splint.

"It was amazing. As soon as the splint was put in, the lungs started going up and down for the first time and we knew he was going to be OK," says Green. In three years, they expect the material will be completely reabsorbed and excreted by the body. By then, his own airways will be able to function on their own, doctors say.

"Severe tracheobronchomalacia has been a condition that has bothered me for years," he added. "I've seen children die from it. To see this device work, it's a major accomplishment and offers hope for these children."

Three weeks after surgery, the ventilator was taken out and Kaiba was sent home. "He’s not walking yet, but he’s starting to learn how to scoot backwards on his little butt,” Gionfriddo says.

Now, Kaiba’s 6-year-old brother and 11-year-old sister spoil him, Gionfriddo says. “They sit there and laugh at him. They end up getting in trouble with them.”

Related: