Scientists have found a possible new way to grow a human liver from scratch, using stem cells that form a “bud”, then transplanting this growing baby liver into the body.

Their work may eventually offer a new way to try to help fill the growing need for organs for transplant. With nearly 17,000 people waiting for a liver transplant in the United States, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, the need is dire.

They’ve only tried their approach in mice so far, and it would be years before they could start testing it in people. But they used human cells in their experiment and the little pieces of liver that grew in the mice functioned as human liver, not mouse liver.

It might be eventually possible to grow little liver buds and “seed” them throughout a damaged liver to help regenerate healthy tissue, the researchers report in the journal Nature.

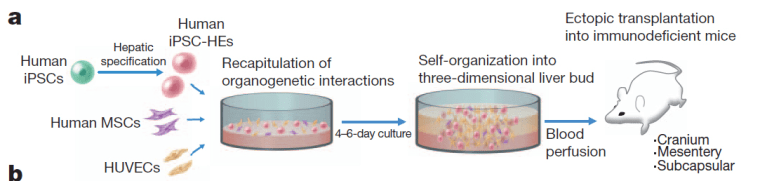

Takanori Takebe, Hideki Taniguchi and colleagues at Yokohama City University in Japan used a certain type of stem cell called an induced pluripotent stem cell, or iPS cell. These cells can be generated using mature tissue – like a piece of skin from someone. They’re genetically manipulated to make them revert to an embryonic state, when each cell has the potential to become any type of tissue or organ in the body.

“To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the generation of a functional human organ from pluripotent stem cells,” the team wrote in a letter to Nature.

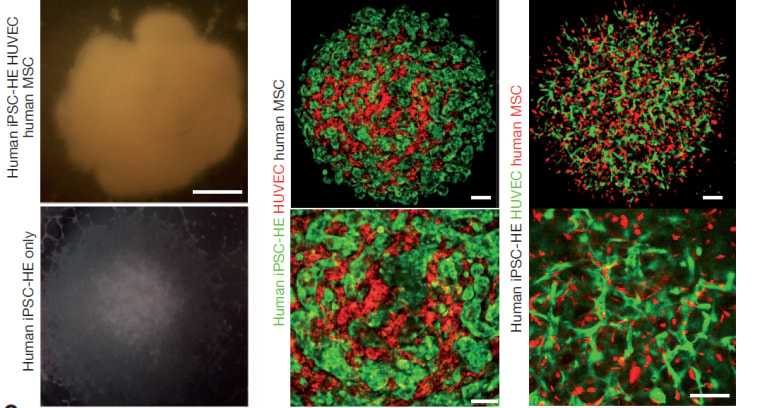

Takebe’s team took a batch of these iPS cells and got them started down the road to becoming liver cells using chemicals and human proteins. They were experimenting with various ways to get these to become mature liver cells in lab dishes, and one group threw these immature liver cells into a dish with two other types of immature cells – one taken from human umbilical cords, and another from bone marrow.

This resembles the mix in an early developing embryo’s body and the liver cells unexpectedly started to grow – not just in flat sheets, as cells in lab dishes often do, but in three dimensions. Not only that, they differentiated into different types of liver cells.

Takebe says he was “gobsmacked”. “They self organized and formed three-dimensional tissue we call liver buds,” he told reporters on a conference call. These buds are usually seen in developing humans at about five to six weeks of gestation, he said.

“We basically mimicked this early liver-bud-forming process,” Takebe said.

They transplanted these little liver buds into mice and watched them grow.

Various tests showed they functioned like liver, and incorporated into the bodies of the mice – even growing little blood vessels that hooked up with the blood vessels of the mice.

“The next important test is how to make a huge amount of liver buds for transplant use,” Takebe said. The liver is the largest solid organ in the body, and to repair or replace one would take tens of thousands of the little liver buds, he says.

It’s likely to be a decade at least before the method could be tested in people. For one thing, the cells need to be made in safer ways to ensure that they don’t become tumors. Some of the first patients might be very young children who have critical liver damage and are likely to die, said Takebe. Their small livers would be easier to regenerate.

Other teams working with stem cells have tried using various scaffolds to get them to make a three-dimensional organ. Some of these scaffolds are made out of human or animal cartilage. This experiment suggests that if tweaked just the right way, the immature cells can make a whole organ on their own, Takebe says.

The team has already started work trying to make other organs, such as the pancreas and kidney, he said.

Other experts were cautious about the findings. “It is a good piece of basic science work,” said Dr. John Gearhart, a stem cell expert at the University of Pennsylvania. “This is a good start, again employing basic science to form a bud, but long way off for producing truly functional hepatic (liver) tissue for the clinic.”

Gearhart says scientists often get into trouble when they try to move from growing tiny bits of tissue from stem cells to growing large amounts. He says it will be a challenge to grow tissue in the quantities needed and to get larger chunks of liver tissue to function as well as the smaller bits do.

The liver is one of the easiest organs to regenerate. Some people have managed with even a piece of a liver transplanted to replace their own dying organ.

A team at the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center has been working to make livers using cells growing on a type of scaffold. They’ve found the growing livers must spend time in a bioreactor to mimic the forces of blood and other pressures in the body.

"We also have strategies that involve printing the organ," said Dr. Anthony Atala, who directs the institute. He says his team, which is working to make a number of different organs for transplant, has avoided using iPS cells because they have the potential to proliferate out of control and grow into tumors.

But Atala said Takebe's team has created an "important system" for studying regeneration. "It's very nice work," he said.