Just in time for Fathers Day, British researchers say they have genetically engineered mosquitoes so they only produce male offspring.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite, so they hope they could use their lab-produced mosquitoes to make populations of the insects plummet in mosquito-ridden areas.

Their lab-engineered mosquitoes are fertile. But the scientists damaged the X chromosome that the father mosquito would normally pass along to its offspring, so that the only young mosquitoes that would hatch alive would be male.

Lab tests showed these altered mosquitoes virtually bred themselves out of existence after a few generations, researchers reported in the journal Nature Communications.

"Essentially the mosquitoes carry out the work for us."

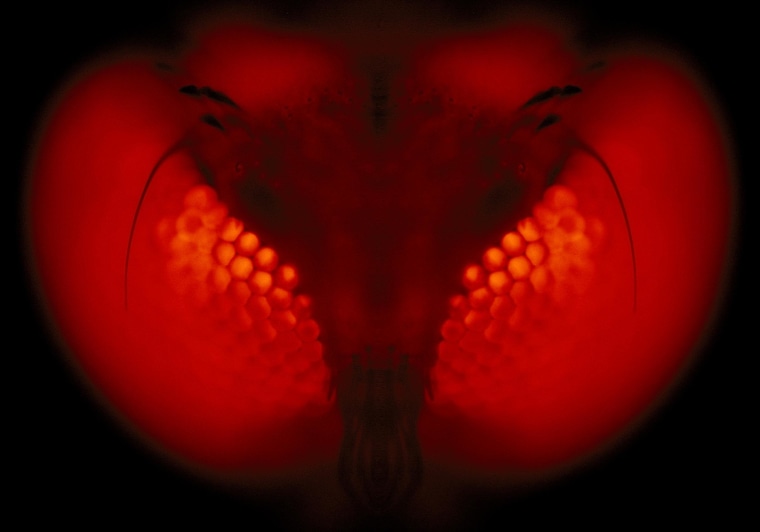

Just like people, mosquito sex is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Males have one X — inherited from the mother, and one Y — inherited from the father. Females have two X chromosomes, one inherited from each parent. So if one is damaged, the female offspring cannot survive.

Usually, about half a male’s sperm will carry an X and the other half will carry a Y. Female eggs carry one X.

The team at Imperial College London has been working for years to create male-only mosquito families, but the method they used to damage the X chromosome ended up killing all the mosquito larvae. Now they’ve perfected the method, Roberto Galizi, Andrea Crisanti and colleagues report.

The researchers spliced a gene into the mosquitoes that slices up the X chromosome when sperm is produced.

“Shredding of the paternal X chromosome prevents it from being transmitted to the next generation, resulting in fully fertile mosquito strains that produce 95 percent male offspring,” they wrote.

Female mosquitoes drink blood when they are producing eggs; male mosquitoes sip nectar.

"What is most promising about our results is that they are self-sustaining,” said Nikolai Windbichler, who helped lead the study. “Once modified mosquitoes are introduced, males will start to produce mainly sons, and their sons will do the same, so essentially the mosquitoes carry out the work for us."

It’s likely that mosquito populations would rebound after a few years, so researchers would have to continually re-introduce genetically engineered mosquitoes. But in theory, the approach could be used to fight all types of mosquitoes — not just the Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes that transmit most malaria, but also Aedes aegypti and other species that transmit dengue, Chikungunya, West Nile and other deadly viruses.

"The research is still in its early days, but I am really hopeful that this new approach could ultimately lead to a cheap and effective way to eliminate malaria from entire regions,” said Galizi.

Outside experts said wiping out mosquitoes would be unlikely to disrupt any ecosystem. "The mosquitoes are not keystone species in their ecosystems. No other animal is dependent on them for food, and we don't rely on mosquitoes to eat anything," said Luke Alphey of Britain's Pirbright Institute.

Other teams are using genetic engineering to fight dengue. One approach introduces a flaw that kills off young mosquitoes before they mature. These mosquitoes are being tested in Brazil, and federal authorities are checking into allowing them to be tried out in Key West, Florida, where dengue is threatening to make a comeback.

"I am really hopeful that this new approach could ultimately lead to a cheap and effective way to eliminate malaria from entire regions."

Another team is infecting the insects with a bacteria called Wolbachia that kills the mosquitoes while they are young and also seems to prevent them from carrying dengue. It’s being tested in Vietnam.

The World Health Organization says malaria infects more than 200 million people a year, and it kills close to half a million children. The parasite that causes the disease can evolve resistance to drugs, and there's no vaccine yet.

There's also no vaccine against dengue, West Nile or Chikungunya. Dengue infects as many as 400 million people a year. Mosquito-borne diseases kill 725,000 people a year, according to the Gates Foundation.