A new brain study may help explain the agonizing and puzzling symptoms suffered by so many combat veterans, from headaches to fuzzy thinking, military researchers reported Friday.

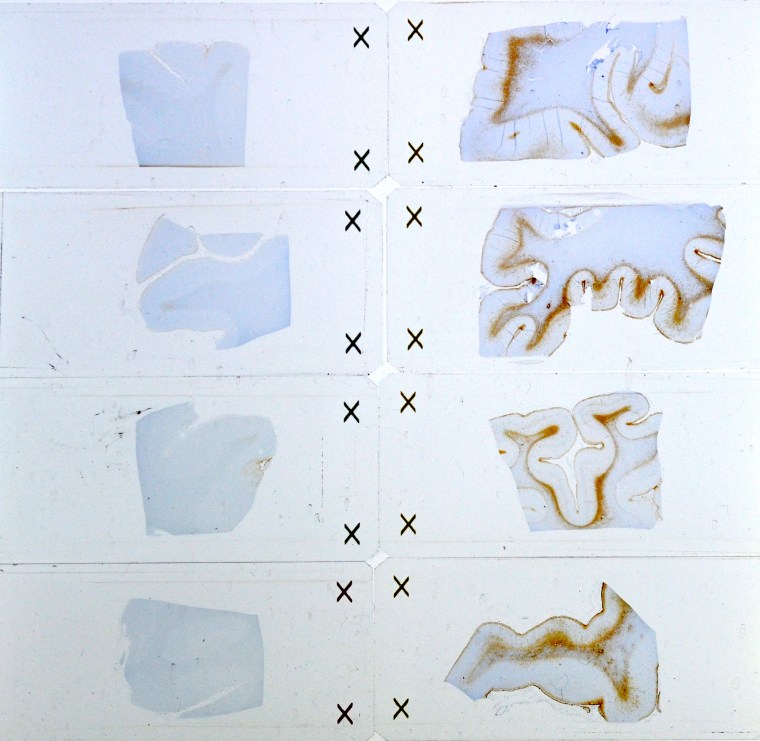

They found a unique pattern of scarring in the brains of men who died days or years after being in or near powerful explosions. The scarring doesn’t look like damage sustained by people with other types of brain injury, such as sports or car accidents, the team at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) in Maryland said.

Now they’re hoping to find a way to see the same damage in veterans who are still alive, and to look for ways to help them.

"What we are detecting is the brain attempting to heal damage and that’s the scarring," Dr. Daniel Perl of USU told NBC News.

The symptoms once were called "shell shock" and they’ve been consistent in war after war: headaches, difficulty concentrating, sleep disorders, memory problems, depression and anxiety. The modern term is traumatic brain injury or TBI.

Related: Study Finds Brain Injury in Living NFL Players

Conventional imaging shows nothing. Sometimes sufferers have been accused of malingering, with consequences ranging from summary execution during World War One to less-than-honorable discharge in more recent times.

Perl and colleagues looked at the donated brains of eight men who survived explosive attacks but died later — some from their injuries, others from causes that may have reflected their suffering: suicide and drug overdoses.

“What we are detecting is the brain attempting to heal damage and that’s the scarring."

They compared them to the brains of 15 civilians, including those with old brain injuries from sports or vehicle accidents. These include people who had abused opioid drugs over time, so as to mirror the cases of the veterans who had abused drugs in case the drug abuse caused a pattern of brain damage.

One of the men whose brain was examined had been a highly decorated career military officer. "Colleagues considered him highly competent, reliable, and emotionally stable," the team wrote in their report, published in Lancet Neurology.

"According to members of his team, they routinely experienced blast exposures during training exercises and combat missions with bombs landing or improvised explosive devices detonating in close proximity," they added.

After he retired, the veteran, who is not identified, said he had not reported his TBIs for fear of being discharged.

"He complained of headache and memory problems and described trouble maintaining mental focus, which he attributed to severe sleep disturbance. He often lost coherence of thought and jumbled his speech."

His wife said he moved slowly, forgot family plans and became uncharacteristically angry. Doctors said he failed to make eye contact but an MRI scan showed nothing unusual. A month later, he shot and killed himself.

Related: Veteran With PTSD Reunited With Service Dog

Perl's team also examined the brains of civilians with chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE, the now-notorious pattern of brain damage most commonly linked with football players.

The two groups do not have the same pattern of brain damage, Perl and colleagues report in the journal Lancet Neurology.

What they saw in the veterans made perfect sense, says Perl, once they saw it.

"Where the scarring is, it's just under the superficial covering of the brain, around the penetrating blood vessels ... (and) at the junctions of the gray matter and the white matter," he said. "It’s basically interfaces between structures that have different physical properties, different densities."

“Now that we know where to look and what we are looking for, I am confident we will find a way to identify this … so we can try to help them."

So for instance, the scarring is where squishy gray matter meets the firmer white matter of the brain.

The veterans whose brain injuries occurred just days before they died had less scarring, Perl said.

"We saw the embryonic formation of a scar,” he said, something that strengthens the theory that the blast itself causes the damage.

Can the scarring be linked directly to symptoms? The headaches, probably, Perl says. He doesn’t want to speculate on the rest.

"However I think it is fair to say that if we are correct, that this scarring produces dysfunction in this area of the brain, this would produce significant problems in terms of functioning and dealing with day-to-day life," he said.

Now it's critical to find a way to identify the scarring in living people, he said.

"Now that we know where to look and what we are looking for, I am confident we will find a way to identify this ... so we can try to help them," he said.