Fred McNeill was no big, dumb football player.

After completing an NFL career that included two Super Bowls, he got an advanced law degree and practiced law. But within just a few years, he began to fall apart, losing his temper, losing his memory and losing job after job.

When he died in 2015, he was bankrupt, unable to eat or care for himself.

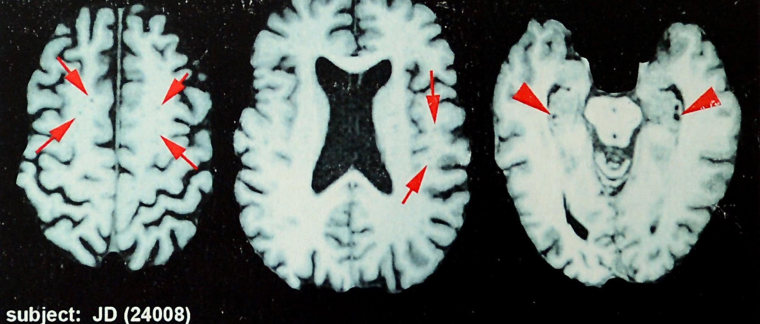

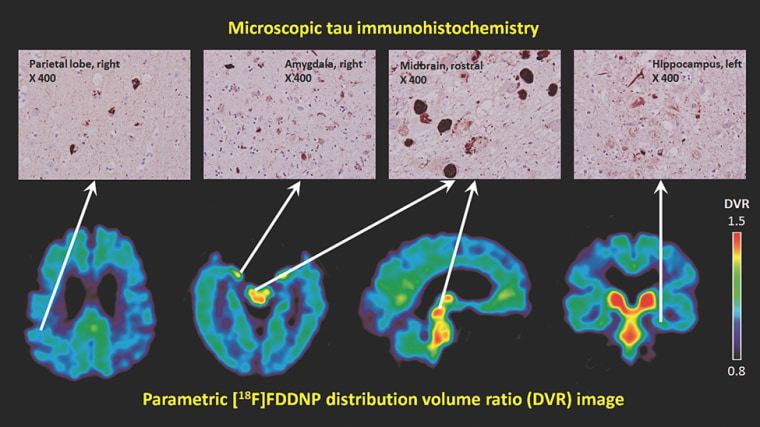

Now he’s become a medical first. A positron emission tomography (PET) brain scan done in 2012 showed he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE — the degenerative brain disease being linked increasingly to professional football and to head injuries sustained in combat.

A thorough autopsy done after his death confirms the diagnosis, pathologists confirmed this week. It's the first time CTE has been diagnosed in a living person with a post mortem confirmation.

The confirmation comes too late to help McNeill. But if the findings hold up in other patients with similar symptoms, such a scan may be able to diagnose CTE in time to give patients hope for recourse while they are still alive and, perhaps, eventual treatment.

Early diagnosis may also help families struggling to understand what is happening to their loved ones, said Tia McNeill, Fred McNeill’s widow.

Related: NFL wives say money won't fix their husbands' injuries

“Here is this person who was so kind, so intelligent, so special, so loving, so easygoing. He made things look easy. And then he flipped to be this other person,” McNeill said in an interview.

“We were just looking at him, not knowing what’s going on.”

She said they quarreled as her once-reliable husband forgot to pay bills and lost jobs.

“He was a partner in a law firm. He had brought in a big class action case … worked on breast implant litigation,” she remembered.

“He was doing big cases. And then he was voted out. At first I thought it was depression.”

"He made things look easy. And then he flipped to be this other person.”

Visits to doctor after doctor told them little but that he may have brain damage related to his many years of playing football. Fred, she said, tried to cover up his struggles.

“Fred would say, ‘don’t say anything. I am going to lose my law license. I don’t want anyone to know,’” she said.

And he would get uncharacteristically angry. “Simple stuff — he would lose it. It was not Fred.”

The story is starting to become familiar — athletes or veterans who are healthy and vibrant, becoming forgetful, angry, combative and often suicidal. Sometimes it happens at astonishingly young ages — former Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez was just 27 when he was found dead in his jail cell, convicted of one murder four years earlier and recently acquitted in two more.

Retired tight end Frank Wainright, who played for the Miami Dolphins, New Orleans Saints and Baltimore Ravens, was 48 when died in 2016 and his wife Stacie said he had struggled for more than seven years with confusion, memory loss and behavior changes.

Trisha Bell told NBC News in 2014 that her husband Nick, who played three seasons for the Raiders, suffers from depression and by age 45 was no longer driving, shopping or paying bills.

Related: Is Football Safe for Kids? New Study Finds Brain Changes

CTE has been found in the brains of more than 100 former football players.

After years of denying any responsibility, the NFL acknowledged there is a link between head blows and brain disease and signed a $1 billion settlement to compensate former players.

Tia McNeill hopes for more help now that the links between CTE and football have become more clear.

“I have to believe that the league will become more humane. I just have to believe it. I have to hope they will support families more,” she said.

She tries to help the families of other men affected.

“You know your loved one. You know there is something going on. There’s always a reason when there is a change in behavior or health, and you want an answer.”

Related: NFL wives pick up the pieces

At the very least, it helps to predict what might happen, Tia McNeill said.

That happened the first time she spoke to Dr. Bennet Omalu, the pathologist credited with discovering and describing CTE.

“He was finishing my sentences,” she said.

The changes caused by CTE have become depressingly familiar, Omalu said. “You begin to lose your intelligence. You begin to lose what makes you a human being,” he said.

“You become more impulsive. You become more violent. You may become an alcoholic.”

Omalu is trying to develop his PET scan method into a commercially available test.

“When you are alive and you think you have CTE, we could scan you,” he said.

"This could differentiate CTE from Alzheimer’s disease and from other dementias.”

“You become more impulsive. You become more violent. You may become an alcoholic.”

Having a scan could help settle disputes with the NFL and other former employers and might eventually lead to treatments, Omalu added.

The behavior that put so many pro athletes into the headlines in past decades may not have been due to life in the fast lane, fame and fortune won too early in life, Omalu said.

It may have been CTE, perhaps not killing them directly, but driving confused young and middle-aged men to early deaths caused by alcohol, drugs or accidents.

“People would say, ‘oh, he had it all and how could he do that?’” said Tia McNeill.

“Now we know it’s a disease. It’s not a ‘how could he’ thing.”