The deadly Ebola virus that’s killed more than 600 people so far in West Africa may have been smoldering there for years and has almost certainly sickened people who thought they had something else, researchers say.

A new study of blood samples from people being treated for a serious, viral-like illness in years past in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia suggests some of them could have been infected with Ebola. Now researchers are digging deeper to see if the virus has always been lurking there, just undetected.

Sign up for health news direct to your inbox.

It’s not a perfect test — the blood samples were several years old and had to be heat-treated so the researchers would be safe — but it’s a lead worth following up, said Randal Schoepp of the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) team that did the research.

“It had been circulating there for a long time,” Schoepp told NBC News. “It just hadn’t gotten out of control or the right conditions weren’t there.”

“It had been circulating there for a long time."

Other researchers said the tests used are not 100 percent reliable, and more testing will be needed to see if they reflect what’s really happening. But it would be unlikely for a virus such as Ebola to appear completely out of the blue in a region. Experts suspect bats and perhaps other animals, too, carry the virus.

“It makes us realize that you don’t have to see an outbreak (to know a virus is circulating in an area),” Schoepp said. “In Africa, it is easy for a disease to smolder because there is so much disease.”

Ebola has killed at least 613 people in Guinea, Sierra Leone and West Africa in an outbreak that started in spring, according to the World Health Organization. It’s been diagnosed in 982, making for a mortality rate of more than 60 percent.

The WHO and Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) both say the outbreak is out of control. It killed 25 out of 28 nurses in a single hospital in Sierra Leone and patients are disappearing into the forest rather than seek treatment.

Ebola had never been seen in West Africa before, although there are plenty of other nasty infections, from malaria to dengue and, especially, Lassa fever. Lassa fever is caused by a virus unrelated to the one that causes Ebola but causes similar symptoms, include high fever, vomiting and internal and external bleeding.

Lassa is a far bigger problem than Ebola — it infects between 100,000 and 300,000 people a year in West Africa, killing 5,000, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

So when someone shows up with a fever in West Africa, Lassa is a prime suspect.

Several U.S.-based organizations have been studying Lassa in Sierra Leone in the decade since a civil war there ended. But not everyone has Lassa or malaria — the majority of infections are never diagnosed.

“Generally only 30 percent to 40 percent of samples tested are positive for Lassa virus,” Schoepp’s team wrote in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

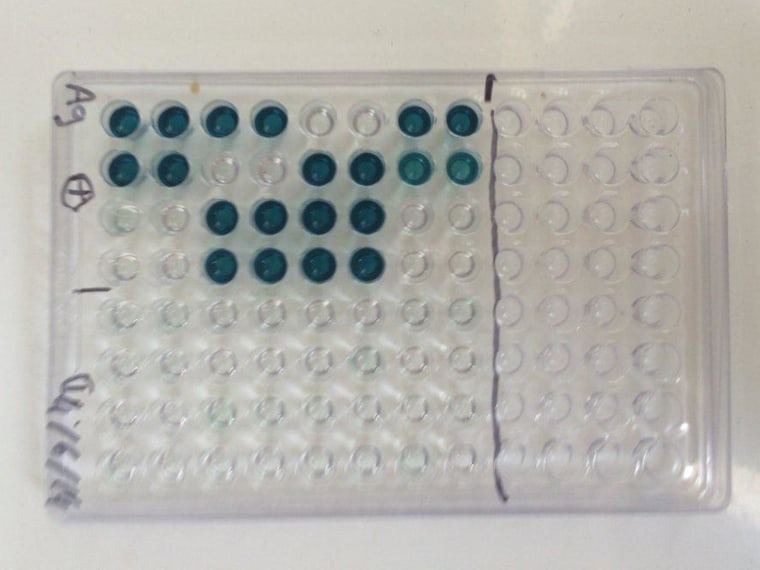

Schoepp’s team looked at blood samples taken from 253 people cleared of both Lassa and malaria between 2006 and 2008. “Most samples were from acutely ill patients from eastern Sierra Leone; some were submitted from Liberia and a few from Guinea,” they wrote.

They found lots of evidence that people were suffering from dengue fever, and chikungunya — both of which are carried by mosquitoes and both of which have been in the news because they are also spreading in the Western Hemisphere. To their surprise, they also found evidence people had been infected with Ebola and the related Marburg virus. Nearly 9 percent of the samples that were clear of everything else tested positive for antibodies to Ebola and nearly 4 percent to Marburg.

That doesn’t mean 9 percent of everyone sick with fever has Ebola, but it does suggest that at least a few people with mystery fevers may have had Ebola. More testing strengthened the evidence, Schoepp said. Likely no one noticed because no one had looked for Ebola before.

“It is often the case that if you look hard enough, you find something almost everywhere,” he said.

WHO officials say Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia lack a good public health infrastructure. Hospitals are poorly staffed and have little equipment. There’s no one to test most sick people to see what they have.

But there are good reasons to try and find out what illnesses are circulating. Lassa can be treated with an antiviral called ribavirin. There’s no specific treatment for Ebola, and it’s important to isolate patients and take strict precautions, including the use of gloves and masks, when treating them. Malaria and dengue aren’t passed person-to-person so patients with those infections do not need to be isolated.

“You can see the relief on the patient’s face when you can tell them, ‘No you are not infected. You can go home and see your family’,” Schoepp said.

“There is a huge social stigma to Lassa infections and now Ebola infections. Even if they survive, there is a good chance they’ll be kicked out of their village. They’ll be shunned by their family.”

Schoepp says his study also shows there is still a lot of mysterious illness in West Africa. “This whole study I did, we could only attribute a possible cause to 28 percent of these samples,” he said. “That means we are still looking at a couple of hundred samples that we have no way of knowing what was making them really, really sick.”

“You can see the relief on the patient’s face when you can tell them, ‘No you are not infected'."

The most reliable testing is done when people first get sick. These tests can detect actual virus circulating in the body. By the time most people in West Africa show up at a clinic or hospital with a viral disease, they’ve been sick a few days and the virus itself may not be easy to find in the blood any more.

“Virus hunting is not as easy as people think,” Schoepp said.

Ebola had only been seen in central Africa and parts of eastern and southern Africa before. The biggest previous outbreak affected 425 people in Uganda in 2000, killing 224 of them. This one is different because it’s crossed borders and it affecting both urban and rural areas.