If you find competitive eating contests hard to stomach, imagine what it's like being the stomach of a competitive eater.

In the 2013 Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest, legendary eater Joey Chestnut scarfed down a record 69 hot dogs — at 290 calories each for a whopping total of 20,010, more than a week’s worth of calories — in a mere 10 minutes. The winner in the women's category was Sonya Thomas, who downed 36.75 hot dogs.

How is that even possible?

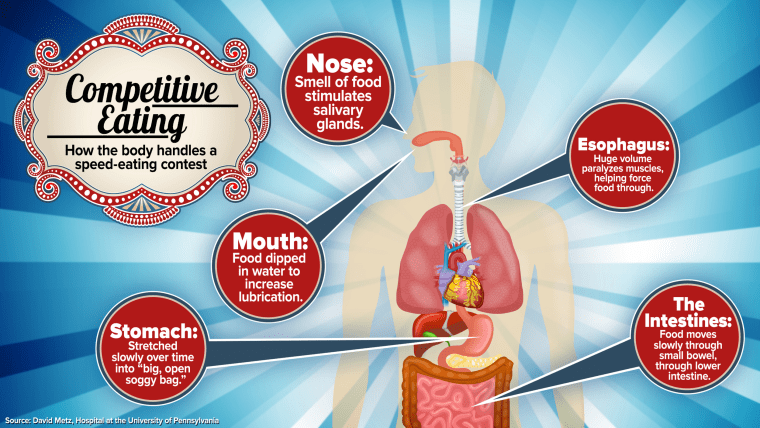

Professional speed eaters like Chesnut, Takeru Kobayashi, nicknamed "the tsunami," or Molly Schuyler are not like us. They have suppressed gag reflexes and can control their esophagus muscles. While they aren't usually overweight, they have larger than normal stomachs, which have been slowly stretched out over time until becoming "a big, open soggy bag," according to David Metz, professor of medicine at the Hospital at the University of Pennsylvania.

Metz and colleagues studied speed eater Tim Janus for a study published in the American Journal of Roentgenology in 2007.

On Thursday, reigning champs Joey Chestnut and Sonya Thomas joined TODAY. Anchor Matt Lauer asked Chestnut, who has been competing for 10 years: "How much longer can your bodies take it?"

"I’m feeling good," said Chestnut. "My body’s healthy and responding well and my doctor’s happy with everything. As long as I’m maintaining my weight and healthy and having fun, I’ll do it."

“Yeah, me, too,” said Sonya, whom anchor Tamron Hall called "tiny and mighty."

Other than the Pennsylvania study, not much is known about what it takes to be a successful speed eater. Metz believes it's a combination of training and genetics.

Leading up to a competition, some speed eaters drink massive amounts of water or gorge on cabbage to expand their stomachs, without adding too many calories, says Metz.

Chestnut told TODAY he's fasting. "I’ll make sure my stomach is loose by drinking liquid — but empty, no solid food. I’m pretty much a cleanse beforehand making sure I can take in a massive amount of food tomorrow."

During the actual contest, the competitors dip their hot dogs and buns in water to increase lubrication, making it easier for the dogs to go down. After the eaters hurriedly chew the food, it moves to their esophagus just as it would with a normal eater. In a speed eater's esophagus, the muscles most likely become paralyzed, suppressing the gag reflex so they don't vomit the food back up.

From there, the food heads to the stomach, which is where speed eaters show the most difference from regular folks.

“The speed eaters have this unbelievable and uncanny ability to uncouple the muscle fibers so [the stomach] becomes a big open soggy bag,” Metz says. While most of us would feel full and our stomachs would distend, causing discomfort and sending a signal that says “enough,” speed eaters do not have the satiety reflex. Many report never feeling full, at least during the competition.

While the top half of the stomach expands and fills up like a storage tank, the lower half of the stomach grinds up the food into a smooth paste called chyme. If the chyme flows too fast into the small bowel, people experience "dumping syndrome," causing cramping, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. With the vast quantities of food and speed at which they eat it, it seems logical that some speeders would experience dumping, but they don’t. The chyme moves slowly into the small bowel, sometimes taking a few days to completely filter through.

“I think of these guys as the predator of the savanna. They don’t eat often; when they eat, they want to eat as much as (they) possibly can. They evolved to have these big stomachs,” says Metz.

While their blood sugar spikes much like anyone else, the speed eater maintains normal pancreatic function, delivering proper amounts of insulin to keep the blood sugar under control.

Over the next few days, the food continues to move from the stomach to the small bowel and through the lower intestine. Non-speed eaters would experience diarrhea trying to process this much food, but Metz says competitive eaters don’t.

Following an event, they don’t eat and when they resume eating, they eat sparingly.

Maybe the pro speed eaters feel OK in the short term, but the Pennsylvania researchers called competitive eating a "potentially self-destructive form of behavior." In 2011, the American Medical Association came out against speed eating, saying it "sets an unhealthy example for spectators" and that participants risk choking, stomach rupture and vomiting.

Hungry now?