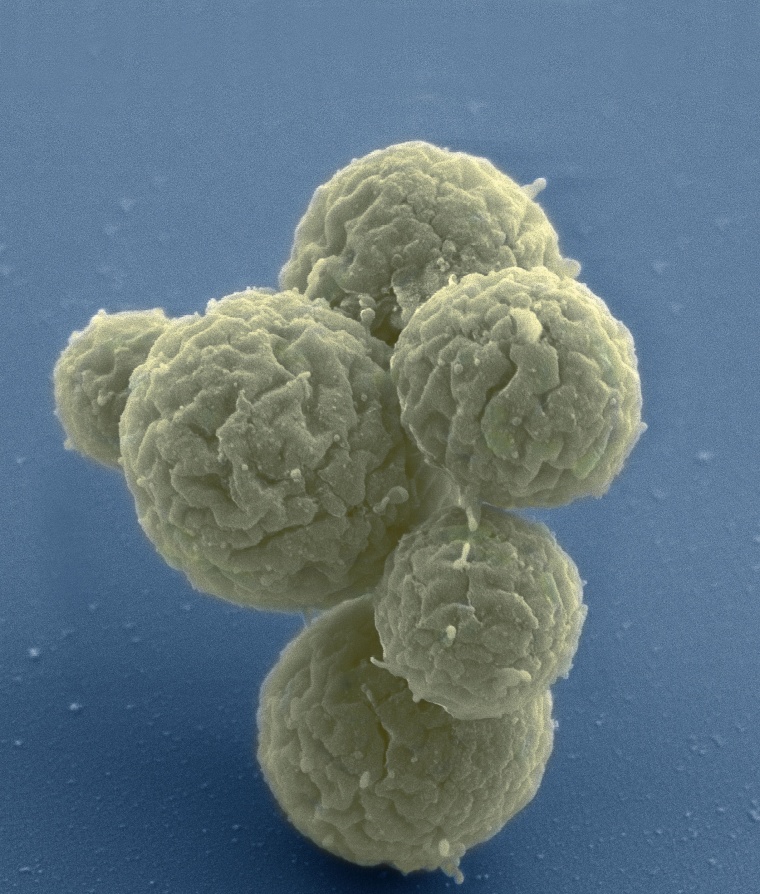

Scientists have created a stripped-down life form, a bacterium with a minimal number of genes needed to keep it going.

They hope to use it as a platform to create designer life forms, and say it’s already taught them some important, and humbling, lessons about the essence of life.

The little bacterium has 473 genes. And the team at the J. Craig Venter Institute in California admit they don’t know what a third of the actually do. They just know the microbe dies without them.

“We don’t know the key elements of about a third of life,” said Venter, who founded the institute.

But they are close, Venter’s team reported in the journal Science.

“It’s the smallest genome thus far known on planet Earth of a self-replicating organism,” Venter told NBC News.

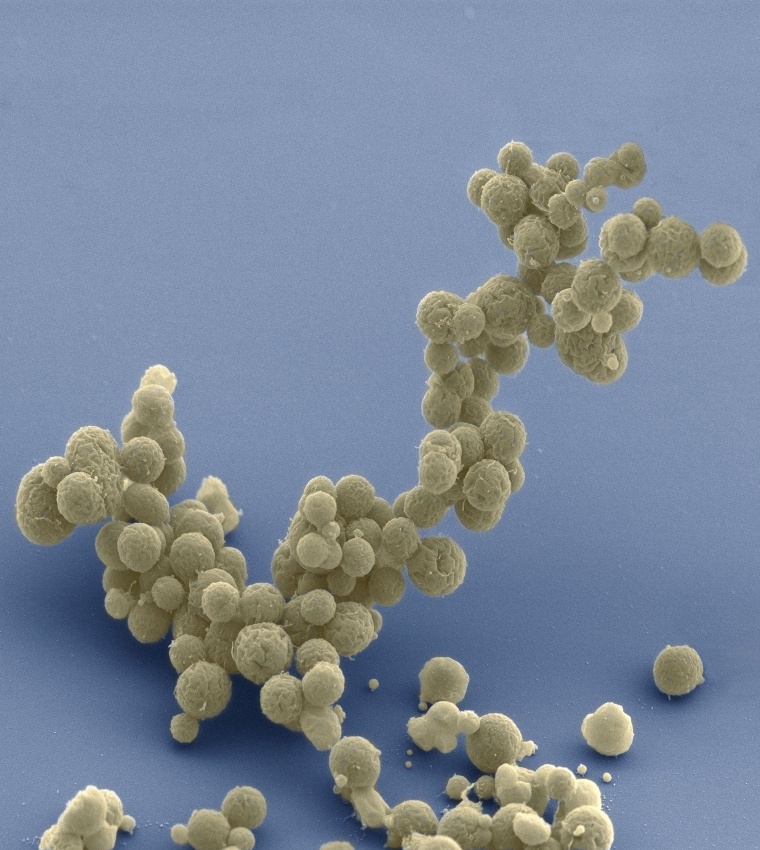

Venter, who helped lead the effort to sequence the full human genome, has been trying for two decades to create synthetic life. His ultimate goal? A system for custom-making life forms on a computer.

“We don’t know the key elements of about a third of life."

“In theory we should be able to add genes to this and evolve it to other species,” Venter said.

But first, researchers have to understand what makes life. To do that, Venter’s team started with one of the simplest bacteria known, one called Mycoplasma. Viruses only have a handful of genes – influenza has eight – but they cannot live on their own. They have to hijack a cell. Bacteria have many more genes, are self-contained and can reproduce on their own.

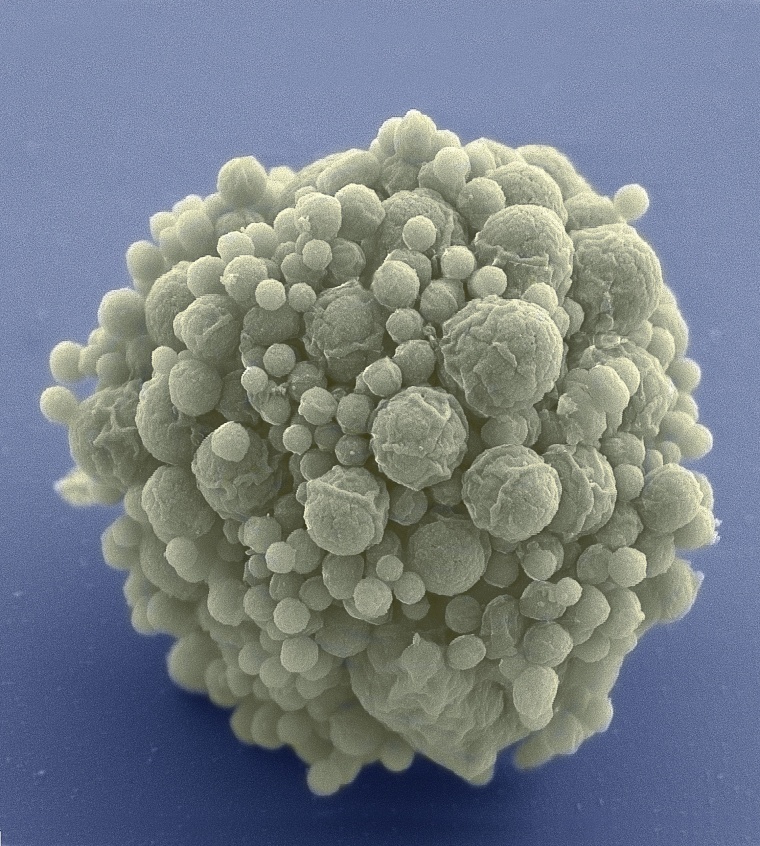

The team selectively took out genes to see what would happen. It’s taken a lot longer and was a lot harder than anticipated.

Related: Artificial DNA Controls Life

“I think one thing I've learned from this is that the whole idea of a minimal genome is not quite as clear-cut as it seemed initially,” Clyde Hutchison, who led the research, told reporters on a conference call.

They found many genes that didn’t seem essential at first, but they learned quickly were part of a pair. One could be taken out, but not both.

“The idea initially was the minimal genome would have only essential genes, and if you knocked out any gene, it would be dead,” Hutchison said. “But the finding of all these quasi-essential genes changes our perspective on this. That if you want a cell that you know grows in a time scale that you can observe, you have to have these quasi-essential genes.”

And now they’ll have to study the other mystery genes, too.

“It actually taught us that we need to be a lot more humble about basic knowledge in biology,” Venter said.

Scientists have been humbled before. They once thought that large stretches of the human genome that did not code for actual genes was “junk DNA”. It’s now clear that junk is essential for making everything work.

Other experts praised the work.

“I think biofuels are out of the picture now as the price of oil bottoms out."

It “represents a remarkable landmark in terms of the ability to deconstruct and understand complex biological systems,” said Samuel Deutsch of the Department of Energy’s Joint Genome Institute.

“It is a very profound result,” added Adam Arkin, director, of the Berkeley Synthetic Biology Institute at the University of California, Berkeley.

Related: Genome Pioneer Warns About Biohackers

Venter has some clear goals in mind and his commercial operation, the Synthetic Genomics Institute, was set up to make products using the stripped-down organisms.

“We think the cell would be a great cell to add components to for manufacturing drugs, and complex chemicals,” Venter said.

Venter had once hoped to manipulate algae or bacteria to pump out cheap biofuels and had a contract with Exxon to do so. They’ve since gone back to the drawing board on that one.

“I think biofuels are out of the picture now as the price of oil bottoms out,” Venter said. “ I think they look a lot more attractive at $200 a barrel than they do at $20.”