Scientists have grown miniature stomachs in a lab dish using stem cells, and are already using them to study stomach cancer. They hope they can grow patches to fix ulcers, find new drugs to treat and even prevent stomach cancer, and perhaps even grow replacement stomachs some day.

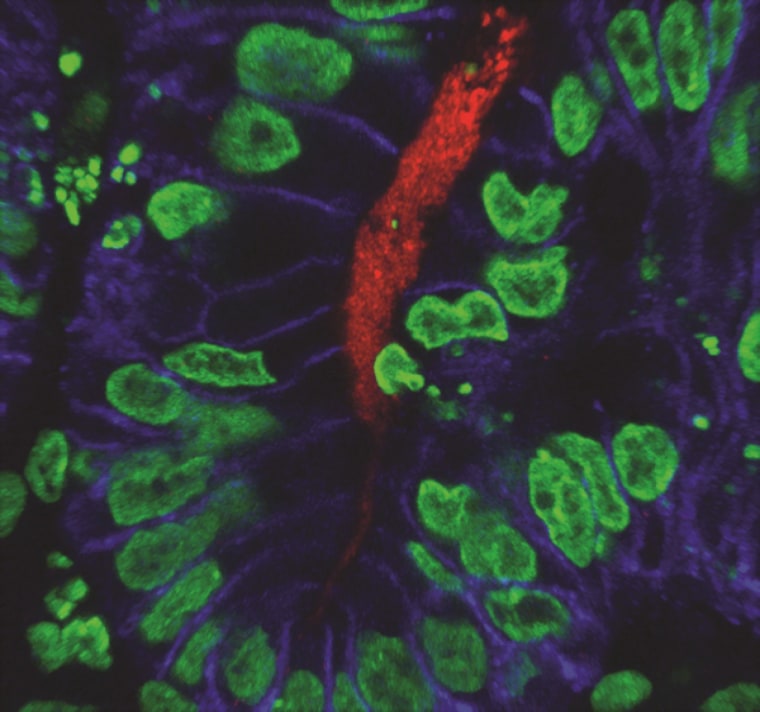

They discovered that the bacteria that cause stomach cancer begin doing their dirty work almost immediately, attaching to the stomach lining and causing tumors to start growing in response. Helicobacter pylori causes many, if not most, cases of stomach cancer, which affects more than 22,000 Americans a year and kills half of them. Stomach cancer is a major killer globally, affecting close to a million people a year and killing more than 70 percent of them.

And the team grew their mini-stomachs using two different types of stem cells — human embryonic stem cells, grown from very early human embryos, but also induced pluripotent stem cells or iPS cells, which are made by “tricking” bits of skin or other tissue into acting like a stem cell.

“In our hands they worked exactly the same,” James Wells of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, who led the research. “Both were able to generate, in a petri dish, human stomach tissue.”

Stem cells are the body's master cells. Embryonic stem cells and iPS cells are both pluripotent — meaning they can give rise to any tissue in the body. They've been used to grow miniature human livers, retinas, brain tissue and have been injected into eyes to treat eye disease.

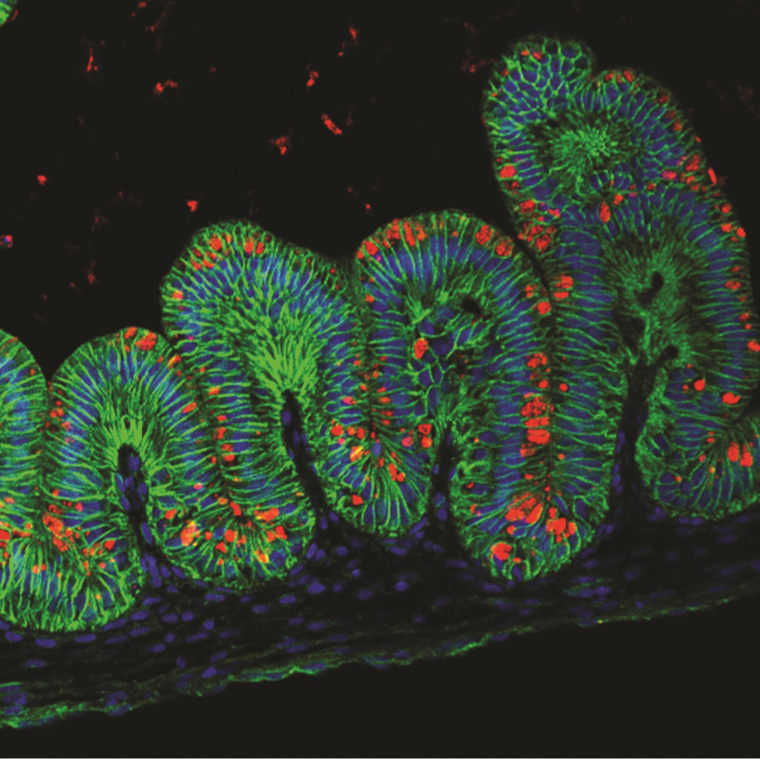

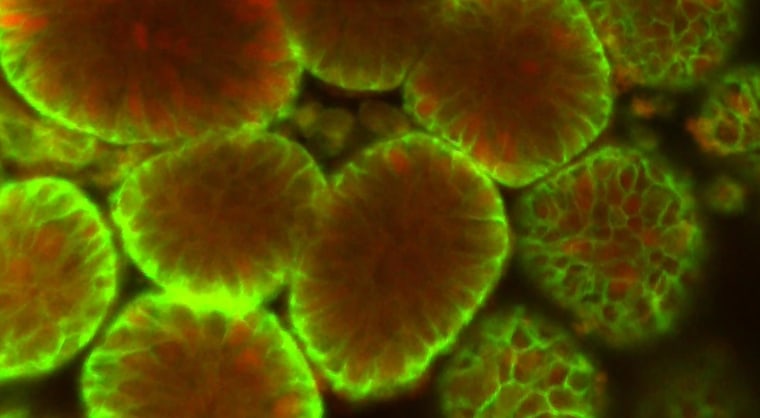

Growing anything close to a real stomach or even a patch for an ulcer is a long way off. The gastric organoids — Wells’s team made the name up — are just about the size of a BB bullet.

It’s not easy getting stem cells to do what you want them to do. Wells and his team, including graduate student Kyle McCracken, had to use various growth factors and chemicals, each introduced at precisely the right time, to coax the cells into becoming three-dimensional blobs of stomach tissue. The stomach is a complex organ, with layers of muscle cells, cells that make up the stomach lining and glands that secrete proteins and acid to digest food.

"The bacteria immediately know what to do and they behaved as if they were in the stomach.”

But the process worked, and the mini-stomachs look just like stomach tissue, the team reports in this week’s issue of the journal Nature.

“We were able to show … that when we inject the bacteria or a little solution of Helicobacter into our little football-shaped mini-stomachs, the bacteria immediately know what to do and they behaved as if they were in the stomach,” Wells told NBC News.

“They bound to the lining and they triggered the early stages of stomach disease. The cells, in response to the infection, started to replicate themselves.”

Helicobacter infects about two-thirds of the world’s population but doesn’t cause disease in everyone. “We want to understand why bacteria trigger stomach disease in some people but not others,” Wells said.

Scientists often use animals to study human disease, but this isn’t optimal with the stomach. Stomach biology and structure differs greatly from one species to the next, depending on what food it eats. Humans have unique stomachs and unique diseases, also.

And Cincinnati Children’s also has its own stem cell facility. One of the many values of embryonic stem cells or iPS cells is that it’s possible to make batches from an individual patient, or from a group of people with the same disease, and study just how their specific tissue goes wrong and how various treatments might work for them.

Another possible line of research: Wells’s team wants to study stomach tissue to help understand why gastric bypass surgery helps people not only lose weight, but works very quickly to start to reverse the symptoms of diabetes.