There's progress in the quest for an AIDS vaccine. An experimental vaccine protected half of a batch of monkeys against a virus similar to the AIDS virus, scientists reported Thursday.

The company helping develop the vaccine is already trying it in people, and vaccine experts say it takes a new approach to trying to protect against a virus that’s proved almost impossible to stop.

“I think it is quite promising,” said Mitchell Warren of the HIV vaccine and treatment advocacy group AVAC.

“In AVAC’s 20-year history we have seen a bunch of products never get to efficacy trials. Those that have have mostly failed,” said Warren, who was not involved in the latest studies.

The two studies reported in the journal Science show that a two-step vaccine not only protects half the monkeys, but that their bodies produce antibodies that can be measured and that show how well-protected the monkeys are.

“We do not know for sure whether a vaccine that protects in monkeys will in fact protect in humans,” said Dr. Dan Barouch of Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Ragon Institute at Harvard, MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital.

But Barouch, who led the study, says he thinks this one may. It’s because the monkeys were first vaccinated and then repeatedly given large doses of an extremely virulent monkey version of HIV called SIV. And the immune response to the vaccine was strong.

“Even protecting half of the people who are exposed to the virus would be a major accomplishment."

The relationship is complicated between the human immunodeficiency virus, which causes AIDS, and the monkey version, simian immunodeficiency virus. Only people can be infected with HIV, and SIV doesn’t cause the same kind of disease that HIV does.

But they’re close enough to test vaccines with, and Barouch says the SIV used in his team’s studies is more virulent than those used in previous vaccine studies. The team also used a combined HIV-SIV virus called SHIV in monkeys, and the vaccine protected 40 percent of them.

Hanneke Schuitemaker, vice president in charge of developing viral vaccines at drug company Janssen, which is developing this vaccine, says she hopes it will work even better in people than it does in monkeys. She notes the monkeys were given a gigantic dose of virus, much more than people get in an average sexual exposure to HIV.

“Based on epidemiological data, we estimate that the risk of a person to become infected per exposure is about 100-fold lower,” Schuitemaker told NBC News.

Making an AIDS vaccine has flummoxed researchers for 30 years, and the need is dire. HIV has infected nearly 78 million people. About 39 million have died, according to the World Health Organization.

There’s no cure.

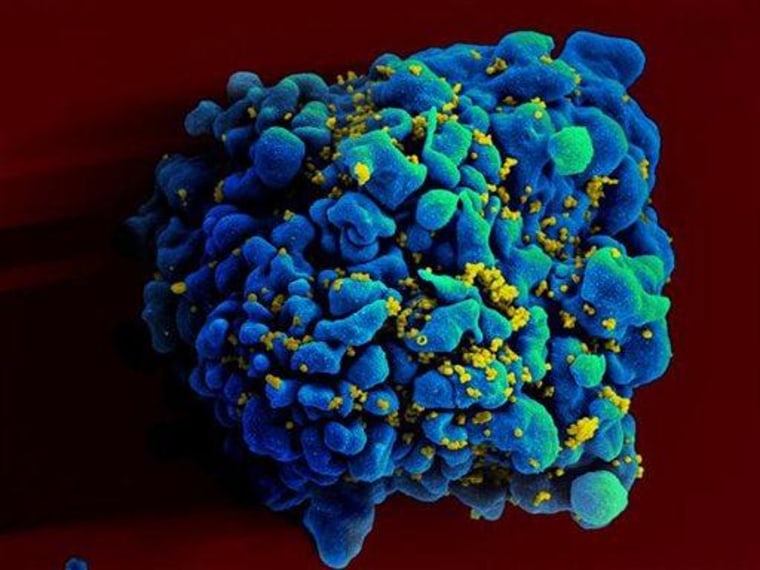

The virus is hard to make a vaccine against for many reasons. It infects the very cells that the body sends to fight it, called CD4 T-cells. It changes its outside genetic envelope, making it hard for the immune system to recognize it. And for some reason, the human body doesn’t produce powerful antibodies called broadly neutralizing antibodies against the virus or against HIV vaccines.

This new vaccine uses a common cold virus called adenovirus 26. As it spreads, it should activate an immune response. Then a second vaccine is given with bits of HIV attached. The immune system cells will also "see" the attached bit of HIV and, the researchers hope, react against any HIV virus should the vaccinated person ever be exposed.

Barouch says it doesn’t stimulate production of the broadly neutralizing antibodies, but the monkey’s bodies did produce antibodies.

“Even if they are not the creme de la crème broadly neutralizing antibodies, they still appear to be able to protect based on a variety of other functions,” he said.

Another team is testing a vaccine made with the same virus, but this one is delivered in a capsule people swallow.

“I do think that their results are impressive,” said Dr. Mary Marovich, who directs the vaccine research program at the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which helped pay for the trial.

“Even protecting half of the people who are exposed to the virus would be a major accomplishment,” added Marovich. “It could ultimately end the epidemic when you use it in combination with other measures.”

Treatment as soon as possible with HIV drugs keeps patients healthy and can help stop them from infecting other people. But a vaccine would be the best way to protect large populations.

“We are not near the end of the epidemic and we won’t be without a vaccine,” AVAC’s Warren said.

Only one vaccine has come even close to working — a combined vaccine tested in Thailand that protected just over 30 percent of the people vaccinated. But it only works against the type of HIV common in Thailand. A version is now being tested in people in South Africa, using the virus most common there.

“This is the first time in quite a number of years that a major pharmaceutical company has sponsored the clinical development of an HIV vaccine candidate."

While about 30 vaccines are in some stage of testing, it’s rare for one to get this far and with this level of support from a company that has its bottom line at stake, said both Barouch and Warren.

“This is the first time in quite a number of years that a major pharmaceutical company has sponsored the clinical development of an HIV vaccine candidate,” said Barouch.

“One of the big limitations of the HIV vaccine field has been the relative degree of reluctance of major pharmaceutical companies to take on the responsibility of a clinical development program.”

Janssen, the drug-making arm of Johnson & Johnson, is sponsoring a trial of the newest vaccine using volunteers in the U.S. and in Rwanda. It’s a so-called phase 1-2 clinical trial, meant mostly to show that the vaccine is safe and stimulates an immune response.

“The company recognizes that the future is in prevention and that we really should work on vaccine that can prevent infectious disease,” said Schuitemaker. She said the company intended to offer the vaccine globally if it turns out to work.

Warren is hopeful but cautious. “There is still a long way to go,” he said.