A detailed study of brain samples of children with autism who died young shows remarkably clear changes in their brains, researchers reported on Wednesday.

The differences are seen both on the genetic level and in the physical structure of the brain, and strongly support what scientists have been saying for years — that autism starts with disrupted genes that somehow interfere with brain development.

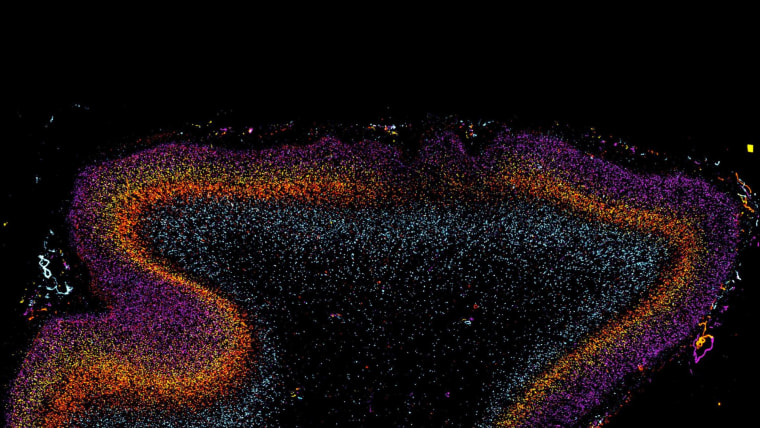

The changes look like patches of arrested development deep in the brain, says Eric Courchesne of the University of California, San Diego’s Autism Center of Excellence.

"They are actually jam-packed with brain cells," Courchesne told NBC News. Not only are there too many cells, but they are not developed properly. "Brain cells are there but they haven’t changed into the kind of cell they are supposed to be. It's a failure of early formation."

It supports the idea that the changes that cause autism are happening in the second and third trimester of pregnancy, Courchesne said.

"Brain cells are there but they haven’t changed into the kind of cell they are supposed to be. It's a failure of early formation."

But the findings also raise as many questions as they answer about the condition, which has been diagnosed with increasing frequency in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The physical changes suggest that something is causing autism that scientists had not identified before, but they don’t shed much light on what that new mechanism might be, Courchesne and colleagues wrote in their report, published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Autism is becoming more and more common among U.S. kids, and researchers don’t quite understand why. The last survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed 2 percent of U.S. children have been diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, which can range from the relatively mild social awkwardness of Asperger’s syndrome to profound mental retardation, debilitating repetitive behaviors and an inability to communicate.

There’s no cure and no good treatment.

Genetics are a large factor — if one twin has autism the other twin is very likely to — but genes don’t explain it all. Better diagnosis doesn’t explain all of it, either, and many scientists are looking at what happens in pregnancy. Some studies suggest that infections such as influenza during pregnancy may play a role.

Courchesne said his team's findings support the idea that both genes and some outside influence are working together to disrupt brain development. "It has to be something that involves mom, something that she is exposed to or that is happening to her," he said.

It’s already known that kids with autism have larger-than-normal brains. One hypothesis is that the growing brain of a child with autism doesn’t “prune” unneeded connections properly, and the resulting overgrowth of nerve connections sends the brain into overdrive.

"This also further reinforces the understanding that autism is caused by genetic factors, and the need to identify autism as early as possible, so that treatment can be started when they have the greatest potential."

For the latest study, Courchesne and colleagues got brain samples from 11 children with autism who died young, mostly from accidents such as drowning, when aged 2 to 15. They compared their samples to brain tissue of 11 kids without autism who also died suddenly.

To their surprise, they found extremely similar changes in 10 out of the 11 children with autism. They found “patches” of abnormal development in the tissue taken from the brain regions important for social development, communication and language. The visual cortex was unaffected.

"That means it’s common. That points to a common time, a common place. And that is startling," Courchesne said.

And the changes were deep in the brain, suggesting that they happened early in development.

“Building a baby’s brain during pregnancy involves creating a cortex that contains six layers,” Courchesne said. The defects were deep among these layers. "It's kind of like looking back in time," he said.

“Numerous brain imaging studies have revealed that ASD (autism spectrum disorder) can affect how the brain functions, but this study takes us to a new level by homing in on changes in the brain’s fundamental building blocks,” said David Smith, head of discovery research at Autism Speaks, which helps fund Courchesne’s work.

What flummoxed the researchers was that the 11 children with autism had a range of symptoms. Many couldn’t speak well and one did not speak at all. Some liked to watch videos quietly, while others showed the repetitive behavior that is one of the hallmarks of severe autism.

Yet the pattern of changes in their brains was very similar. It could be that autism is caused by specific genetic damage, and where that damage occurs affects behavior, the researchers said.

"One of the remarkable things about children with autism is even at young ages, many of them will have very similar degrees of social and language impairment, but some get better and some don't," Courchesne told NBC News.

"So it's always been a big mystery what's the basis for getting better and not getting better," he added. Maybe the brain can re-wire itself, depending on where the patches of damage are, he said.

"This also further reinforces the understanding that autism is caused by genetic factors, and the need to identify autism as early as possible, so that treatment can be started when they have the greatest potential," said Dr. Paul Wang, head of medical research at Autism Speaks.

And Dr. Deborah Fein of the University of Connecticut, who was not involved in the study, said the study shows why it's so important to donate tissue and organs for scientific study.

Hayley Goldbach, the 2013–14 Stanford–NBC News Global Health and Media Fellow, Senior Medical Producer Erika Edwards and Senior Nightly News Researcher Judy Silverman contributed to this story.