A brain stimulation technique approved to treat depression might also help patients conquer cocaine addiction, researchers reported Thursday.

A very small study of cocaine addicts showed the treatments helped 70 percent of them lose their cravings for the drug, the team reports in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology. Some have stayed free of the drug for a year.

“They don’t crave cocaine any more. They get their lives back,” Dr. Antonello Bonci of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse, who helped with the study, told NBC News.

Bonci stresses that much more research is needed but he’s hoping doctors can start testing it, since the technique is approved and widely available.

“They say it feels like a black cloud has been removed from their head.”

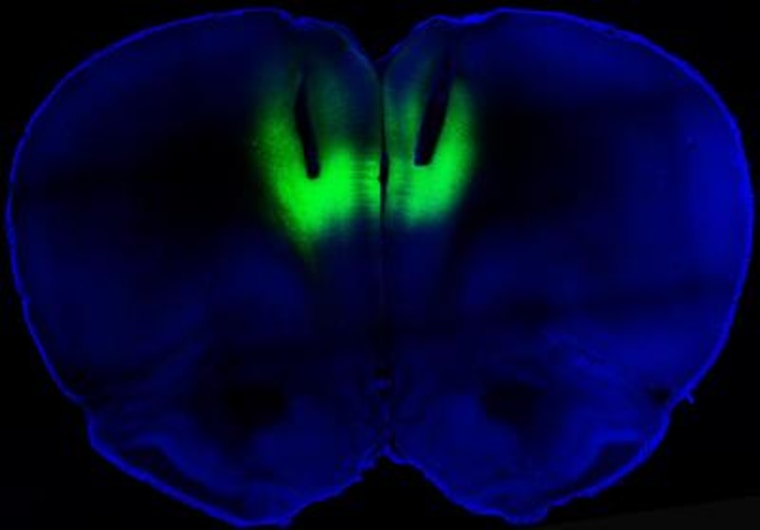

It all started with an experiment Bonci and colleagues did using rats that were addicted to cocaine. They noticed that addicted rats have very low levels of activity in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, which is involved in impulse control and decision making.

“It was basically silenced in these rodents as a result of cocaine exposure,” he said.

They used a different technique called optogenetics to stimulate the rats’ brains. “They immediately lost interest in cocaine,” Bonci said. Optogenetics are too invasive to use in people, but the researchers speculated that a non-invasive technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation or TMS might do the same thing.

The 2013 experiment was widely reported. “The father of a very severe cocaine addict in Italy saw it,” Bonci said. He went to his addiction clinic in Padua, Italy and asked to try it. They bought a TMS machine and were impressed with the results.

“They contacted me. They said, ‘Anto, this is working here’. So the team, led by Dr. Luigi Gallimberti, of the University of Padova (Padua) Medical School, set up a clinical trial involving 32 patients at the clinic, treating half with TMS.

This is small for a trial and the patients were not “blinded” – they knew they were getting TMS. Bonci said that clearly leaves open the possibility of placebo effect. Nonetheless, the results stunned him.

After three months, 11 out of 16 patients treated with TMS had kicked the cocaine habit and drug tests confirmed they were not using the drug, Bonci’s team reported. Only three out of the 16 patients who did not get TMS but who got counseling and anti-anxiety medications stayed cocaine-free.

“It’s incredible how they respond to TMS in terms of how much better they feel, how much they tell you they don’t think about cocaine any more,” Bonci said.

“They say it feels like a black cloud has been removed from their head.”

The team then offered TMS to the 16 “control” patients. Ten tried it, and of those, seven managed to stop using cocaine. “

"It’s working. Something is working in these patients,” Bonci said.

“These patients had on average used cocaine for the past 10 years, four times a week on average,” Bonci said.

He’s followed many informally for a year now. It’s not a scientific result, but Bonci said the effects may be long-term.

“The majority of these patients are still completely cocaine-free,” he said.

He met the young man in Padua who was the first to try TMS. He’d attempted suicide before, Bonci said, but is now raising a baby daughter with his wife. “He said, ‘I don’t think about cocaine any more’,” Bonci said.

"It’s working. Something is working in these patients."

There’s currently no treatment for cocaine addiction, other than support in helping people just not use it. The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that 1.4 million Americans suffer from cocaine addiction.

Bonci would like to see other researchers try it in larger groups of cocaine users with better controls, so they can tell if TMS is really having an effect.

Other teams already are, including one at Columbia University, NIDA says.

TMS, which involves placing a large electromagnetic coil over the head, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for depression in 2008.

It’s been found to have other hard-to-explain effects on the brain. For instance, in one experiment Caltech researchers found that people who receive a mild electrical shock deep within the brain ranked others as more attractive than they did before the jolt.

Other studies found it may help ease ringing in the ears and bulimia.