Vast military research — aided by such new studies as a look at a sky-high brush with death — may help the many civilians suffering from PTSD, the often debilitating and sometimes lethal signature wound of American wars.

In a given year, more than 5 million U.S. adults weather the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, and over the average lifetime, about eight of every 100 Americans will suffer from it, reports the National Center for PTSD, part of the VA. Case in point: A year after the Boston Marathon bombings, about 11 percent of the kids who stood near that race’s finish line were suffering from PTSD, a survey found.

As 15 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans grapple with post-combat anxieties — and as ex-troops and experts link PTSD to military suicides — Pentagon and U.S. Veterans Affairs Department have invested hundreds of millions of dollars to solve the malady's mysteries, including why some people seem more at risk.

That work has prompted potential breakthroughs, including an Aug. 11 announcement that a researcher affiliated with a VA Center in the Bronx had located a PTSD “biomarker” — a genetic clue tied to stress hormones that may explain each person’s vulnerability.

“The increased interest and research in PTSD can only help the cause of civilian PTSD,” said Brian Levine, a neuropsychologist at Baycrest Health Science’s Rotman Research Institute in Toronto. “The misfortunes of soldiers in wars often increase knowledge of diseases or injury effects. World War I and II brought on a great deal of new knowledge about brain function through the brain injuries sustained there.”

Levine co-published a study last week involving 15 survivors of a narrowly averted air disaster over the Atlantic Ocean on Aug. 24, 2001.

Little remembered in America in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 terror attacks, Air Transat Flight 236 — carrying 293 passengers and 13 crew from Toronto to Lisbon, Portugal — ran out of fuel and lost power two hours before its scheduled landing. A quiet, overnight voyage abruptly turned into 32 minutes of torture that included a stomach-churning altitude drop, the eerie absence of engine sounds in a darkened cabin, people’s screams and audible prayers, and pre-impact orders from the crew to don life jackets and “brace, brace, brace!”

The pilot and first officer managed to glide the Airbus A330 — without flaps, reverse thrusters or main brakes — onto an island in the Azores, some 900 miles from Lisbon, slamming down on a paved air strip at an estimated 298 mph, causing the wheels to blow out and erupt in flames. Only minor injuries were reported.

“Everyone was basically going to die, and they lived,” Levine said.

Seven of the 15 survivors who participated in the study experienced PTSD symptoms, which can include intrusive memories, nightmares, sleep trouble, angry outbursts, hypervigilance, overwhelming guilt, feelings of detachment and difficulty maintaining relationships, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Levine’s project was the first PTSD investigation to examine people exposed to the same traumatic event while focusing on their “autobiographic memories” — how much “editorializing” they do about the moment, how often they told lab interviewers things like: “I never thought I was going to make it.”

That revealed a critical difference in who got PTSD and who did not. The 15 test subjects all showed a similar, rich recall of flight details. But the seven passengers with PTSD all related a deeper array of autobiographic comments, suggesting they have a distinct way of processing frightful memories.

“They have more clutter in their recall — extra stuff when they tell the story,” Levine said. “If you are unfortunate enough to get traumatized, it may be that your memory style differentiates those who get PTSD from those who don’t.”

One of the test subjects even lost sleep when he heard Levine’s study was about to be published.

“Just reading something about it, I’ll lose myself in thought, catch myself visualizing it and get sweaty fingers,” said study subject Daniel Goncalves, who was 24 while traveling with his family on Flight 236 to see a dying uncle in Portugal. He was never formally diagnosed with PTSD. “I’m getting goose bumps now, talking about it.”

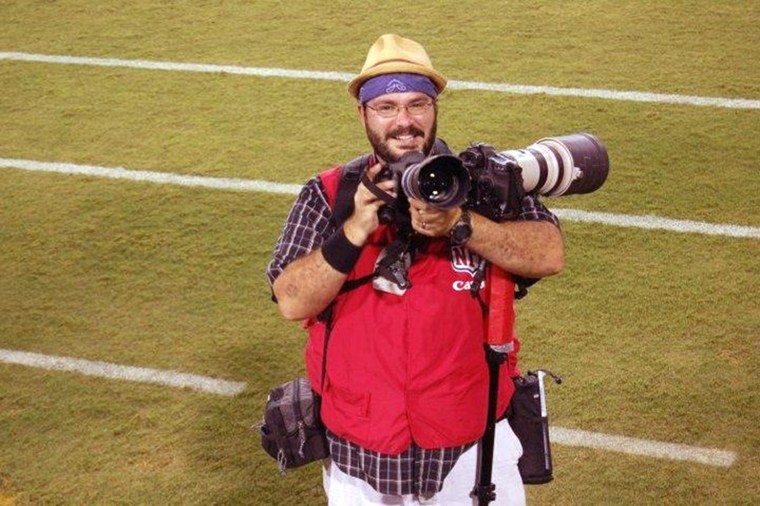

Today, working as a photographer in Dallas, Goncalves, has sometimes shied away from discussing the event. To help friends understand, he wrote a blog post about those the 32 minutes so “I can send them over there instead of going through the whole ordeal and avoid getting emotional.”

His blog account is laced with autobiographic memories, with lines like: “This fully loaded Airbus A330 was going into the ocean and all I knew was that my poor family were there with me. It hit me. This wasn't going to go away. This was it. This really was it. The end. Unimaginable death by catastrophe.”

Goncalves often has heard about PTSD in connection with Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. But he knows combat is not the only potential trigger.

“I guess PTSD is not something people think about outside the wars," Goncalves said. "But (many) people have traumatic experiences that affect you later.”

And putting his hair-raising account in writing has helped Goncalves face his greatest fear again.

On Saturday, he flew the same route, again an Air Transat jet — this time for vacation. He didn't sleep for many nights before his trip. But he made peace with the choice.

"All I wanted was one more second just to see my family," he said of the original flight. "I got that, and I feel like I won the Super Bowl, so if the plane goes down, it’s fine."