Patients with depression often struggle through weeks or months of trial-and-error to find the right antidepressant. Now the burgeoning field of pharmacogenomics — how genes affect a person's response to drugs — is helping more patients avoid debilitating and all-too-common side effects of psychiatric medications.

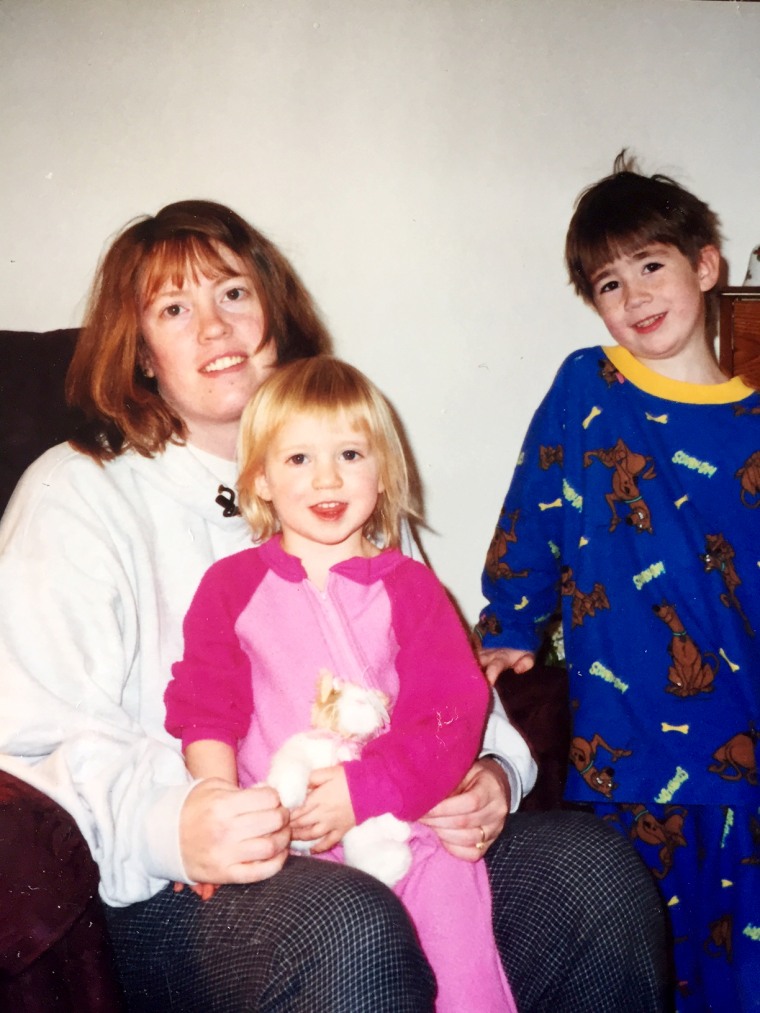

Sarah Ellis will never forget her darkest days battling depression and the series of prescriptions the Sioux Falls, South Dakota mother of three endured.

“I tried every medicine," Ellis, 45, said. "I wondered if I would ever find something that works." One prescription gave her a rash for two years and the anti-anxiety medication, Clonazepam (Klonopin), affected her balance. She was also prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) — a class of drugs including Prozac which are used to treat anxiety and depression — but they "made me feel like I was losing my mind," Ellis told NBC News.

More than 1 in 20 American, ages 12 and older, are struggling with depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And many more are suffering from sometimes severe side effects, like weight gain, nausea, sleepiness and sexual problems. At least 135,587 adverse drug reactions linked to antidepressants were reported to the Food and Drug Administration's Adverse Event Reporting System between 2004 and 2012.

It's unclear how many patients have had to stop or chosen to stop treatment for depression due to side effects.

Related: 5 Things You Need To Know Before Taking an At-Home Genetic Test

Ellis tried 23 different combinations of depression medications. Finally, her psychiatrist, suspicious that her body might process medication differently than most, recommended a genetic test to see why Ellis wasn’t responding to the prescriptions.

“Once the genetic testing became available it provided Sarah with more than just physical relief," says Dr. Matthew B. Stanley of the Avera Medical Group in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. "It gave us an answer — that this was her physiology and her genetics and not something in her head.”

The Avera Institute for Human Genetics (AIHG) in Sioux Falls, South Dakota is among several institutions exploring the role of pharmacogenomics — the science of how our inheritance and genetic makeup influences the way we metabolize medications.

Related: Is Your Medication Helping or Hurting? DNA Tests May Be a Guide

'One piece of the puzzle'

AIHG’s pharmacogenomics research has led to the development of Genefolio, a genetic test that uses an individual’s unique DNA to predict how that individual will respond to medications. The test offered by Avera is $179 and is often covered by insurance.

Research pharmacist, Krista Bohlen, director of personalized pharmaceutical medicine at the Avera Institute for Human Genetics, believes that genetics play a large role in how different individuals react to certain medications, but cautions doctors and patients against relying solely on this method for answers.

According to a study conducted by the Mayo Clinic that looked at one genetic test similar to many used in hospitals — GeneSight Psychotropic — symptoms of depression were reduced by 70 percent compared to treatments prescribed without genetic testing.

While the results are striking, this technology is not a guarantee of complete resolution of depressive symptoms or medication side effects.

“Pharmacogenomics is one piece of the puzzle," Bohlen told NBC News. "We look at it as a tool to help the physician. They can couple their expert opinions with information from the patient, like their symptoms and family history, to look more closely at one class of drug over another."

The Genefolio test confirmed gene variants within Ellis’ DNA that made her more susceptible to certain side effects with newer classes of medications, so Stanley prescribed an older class of antidepressant and experimented with a lower dose.

It worked for Ellis.

"My energy's been really great," she says. "I feel like I can accomplish what I want to accomplish. This was definitely worth it.”