John R. Brown had been on medication for depression and bipolar disorder since high school, but with personal crises swirling, he was desperate for help coping. So when his doctor suggested taking an expensive genetic test to find better treatment, he readily agreed.

“It was so simple,” said Brown, a 40-year-old former editor from Rutland, Vermont. “Just a matter of swabbing my cheeks for DNA and sending the test away.”

But when his doctor changed his medication, based on those test results, Brown’s symptoms became much worse. Within a month, he had voluntarily checked himself into a psychiatric hospital on the brink of suicide.

Now, an investigation by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting, published Sunday in the Boston Globe, has found that the reliability of these new tests, used to guide doctors in prescribing medicine for an array of neuropsychiatric conditions, is uncertain.

“Genetic tests to identify the most effective psychiatry drugs are the hot new thing in the race to create personalized treatments based on people’s DNA,” says NECIR reporter Beth Daley.

“The take-home is you don't know if they work or not because no one has ever independently checked them out,” she told NBC News.

Daley’s investigation has revealed that in the last three years, about 600,000 of these tests have been ordered by doctors for patients who suffer from common conditions like depression, attention deficit disorder and anxiety.

Test manufacturers see the potential for a lucrative market: An estimated 43.8 million Americans — 18.5 percent of all adults — have a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

These new DNA tests are based on small studies by the companies who manufacture them, opening the possibility of conflict of interest, according to Daley. And there is little oversight for consumer safety because, for now, they do not require Food and Drug Administration approval.

Just this month, an article urging clinicians to be aware of the "potential limitation" of these tests was published in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders.

"Not only polygenetic influences, but life circumstances, and interpersonal and environmental interactions can shape many mental health conditions," writes author Dr. Robert Klitzman, professor of psychiatry and director of the Bioethics Masters and Online Certificate and Course Programs at Columbia University.

Other critics say companies are marketing tests to people who are desperate and want something to help them.

Dr. Alexander Bystritsky, director of the UCLA Anxiety Disorders Program, said that he does not prescribe these genetic tests because they have a “low predictive value at a high cost and [add] additional time.”

“Genetics should not be a substitute for good clinical assessment and clinical judgment,” he told NBC News.

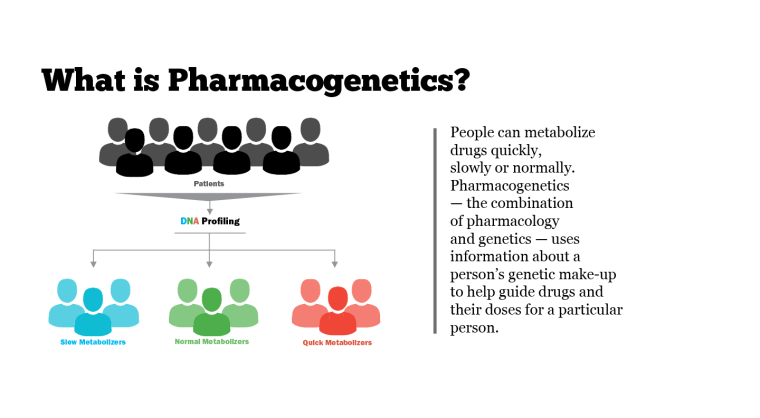

The technology behind this new science — pharmacogenomics — was developed at the respected Mayo Clinic and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. And many insurance companies have begun to cover the tests.

In 2014, a test called GeneSight, manufactured by Assurex Health, was approved by the federal Medicare program to treat depression. The company was also given a contract with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to help guide psychiatrists in treating post-traumatic stress disorder.

But GeneSight was the same test that failed Brown. His doctor switched him from the antidepressant Effexor to Fetzima, a drug the test deemed more genetically appropriate.

“I was trying to find something to jumpstart my mood,” said Brown. “Instead, I had lower energy and found myself sleeping more. I also had a lot of suicidal ideation.”

But Assurex Health stands by GeneSight as one more tool in the doctor’s diagnostic toolbox. The company cites five studies published in peer-review journals that show its efficacy and cost effectiveness. Twelve more industry studies are ongoing.

Virginia Drosos, Assurex’s president and CEO, said that finding the right medication for a psychiatric patient is a trial-and-error process that “can last months or years.”

“Even when a doctor makes a perfect diagnosis to use psychotropic medications, there are 38 to choose from,” Drosos told NBC News. “The doctor has to take a best guess for a good match. And we know from industry studies that half the time, they don’t guess right.”

The GeneSight test gives doctors a “traffic lights” guide to FDA-approved medications based on a patient’s genotype. Drugs marked “green” can be prescribed without many side effects; “yellow” ones should be used cautiously; and “red” drugs should be avoided.

The test looks at genetic mutations, as well the patient’s metabolization rate, among other markers.

“It’s not just metabolization we are looking for, but how the medications work in the brain and what receptors it binds to that also control how we respond to a medication,” said Bryan M. Dechairo, the company’s senior vice president, medical affairs and clinical development.

“There are multiple factors in how a patient responds, and we can take away a lot of the guessing,” he told NBC News. “A doctor is picking from a smaller list.”

Dechairo said GeneSight has doubled medication success rates from 25 to 50 percent.

Its studies of patients who had failed one or more medications showed a 23.7 response rate; with GeneSight, that rate was 44. percent, he said.

“You can’t make every medication work for everybody, but if the doctor didn’t have GeneSight, three out of four patients wouldn’t get better,” he said. “We still have a ways to go. We need new drugs, but we can still get the efficacy higher.”

Ronni Shapiro, a 58-year-old special events planner from New York City, said she is a GeneSight success story. She had been on at least 12 medications, none of which had helped her depression, and had been hospitalized twice.

“I went through a traumatic divorce and wound up suicidal,” she told NBC News. “They would try one medication and then another. … I gained 10 pounds, lost 10 pounds, couldn’t sleep. I was ready to throw myself out a window.”

Eventually, a nurse practitioner suggested Shapiro find a psychiatrist to prescribe GeneSight and results showed a genetic mutation that explained her inability to respond to her medications. A psychiatrist added Wellbutrin and it worked.

“One week from the day I started it, I was a totally different person, physically and emotionally,” said Shapiro, who was so grateful, she offered to be an uncompensated spokesperson for GeneSight.

“Does it work for everyone? I don’t have a clue,” she said. “But it helped me and what’s the risk?”

But sometimes, a genetic test can’t really help at all.

For example, Jerod Poore of St. Regis, Montana, paid $3,800 for the GeneSight test and learned he was on the right medication all along for his bipolar disorder and social anxiety. The 53-year-old said he had tried more than 25 medications and was still “treatment resistant.”

But, Poore, who runs the website Crazy Meds, told NBC News, “It was worth it. I was just looking for answers to what I had been going through for 20 years.”

As for John Brown, he has been released from the Vermont psychiatric hospital since his bad experience and is back on his old medications.

“I’ve stabilized,” he said. “I’m not stellar, but at least it’s better than it was before.”

He warns other patients not to “rely too heavily” on these new genetic tests. “It’s just a diagnostic indicator,” said Brown. “Definitely take it with a grain of salt.”