Scarlet fever plays the villain in some of the best children's books: It got "Little Women's" Beth March. It got the child in "The Velveteen Rabbit" (although the kid survives, so, really, the fever got the stuffed rabbit). And it robbed Mary Ingalls, sweet sister of "Little House" series author Laura Ingalls Wilder, of her sight.

Or so we were told. But today, the journal Pediatrics asserts that it wasn't scarlet fever that caused Mary's blindness -- it was viral meningoencephalitis, an inflammatory disease that attacks the brain.

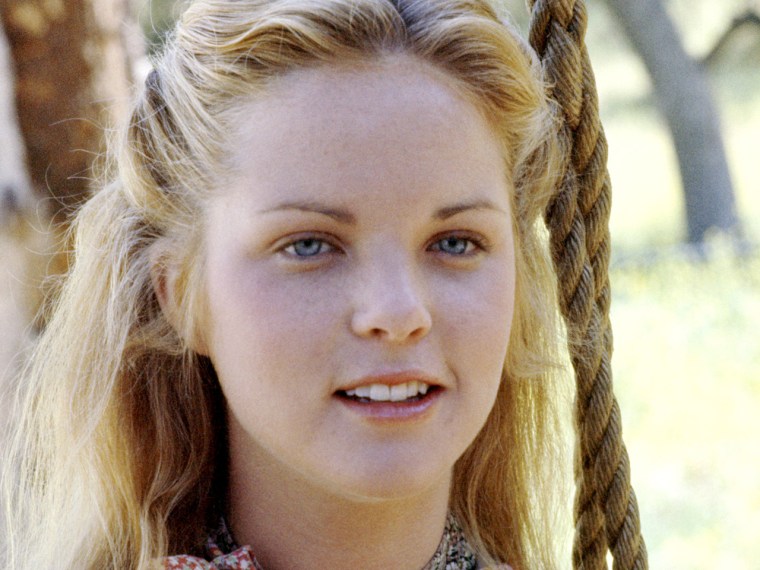

This is the sort of thing that is extremely interesting if you are interested in this sort of thing. And we'd wager many people are: The "Little House" books have remained in print ever since the initial publication of "Little House in the Big Woods" in 1932, and they're still popular today, with three titles landing on the School Library Journal's 2012 list of best children's chapter books. Even if you never read the books, you probably remember the TV series, which aired from 1974 to 1983.

Dr. Beth Tarini, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan, and her co-authors make their claim after scouring epidemiological data on blindness and infectious disease around the time of Mary's illness, plus analyzing local newspapers and Laura's unpublished memoir, "Pioneer Girl." For Tarini, it's the culmination of a project she began in medical school 10 years ago, after a confusing conversation with a professor.

"I was in my pediatric rotation, and we were talking about scarlet fever," says Tarini. She remembers commenting that scarlet fever can make you go blind. "The professor said, 'No ...,' and I said, 'But Mary Ingalls went blind!' ... So I got on a detective mission of sorts."

Mary Ingalls did indeed lose her sight when she was 14, in 1879. Here's the line from the "Little House" novel "By the Shores of Silver Lake": "Mary and Carrie and baby Grace and Ma all had scarlet fever. Far worst of all, the fever had settled in Mary's eyes and Mary was blind."

Laura might've attributed Mary's blindness to scarlet fever to make it easier for children to understand, Tarini says. Readers were familiar with scarlet fever as literary device, but less so with "brain fever," as meningoencephalitis was called then.

In the mid-1800s, scarlet fever was one of the most fatal infectious diseases among American children, with case fatality rates ranging from 15 percent to 30 percent. "As late as 1910, scarlet fever was cited as one of the top four causes of blindness, along with measles, meningitis, and 'other diseases of the head,'" the authors write in the Pediatrics article.

But just before "By the Shores of Silver Lake" was published, Laura wrote this in a 1937 letter to her daughter, Rose: "Mary had

spinal meningitis [sic] some sort of spinal sickness. I am not sure if the Dr. named it. We learned later when Pa took her from De Smet, South Dakota to Chicago, Illinois to a specialist that the nerves of her eyes were paralyzed and there was no hope." And the register for Mary's school, the Iowa College for the Blind, lists the oldest Ingalls girl's cause of blindness as "brain fever."

Tarini and her co-authors matched these clues with the description of Mary's illness in Laura's memoir, and mentions in the town newspaper, and all signs pointed to meningoencephalitis. Mary probably caught the virus like any of us catch a virus today, with the added risk factor of living in close quarters, making it easier to spread diseases.

Mary's meningoencephalitis likely caused optic neuritis, or inflammation of her optic nerves, which resulted in her vision loss.

Besides settling a 10-year score with a med school professor, Tarini says the purpose of the paper is to remind physicians that their perception of a disease is often very different from their patients' perception. Even today, Tarini says, if she tells parents their child has scarlet fever, they get really worried: "They look aghast! And in my head, I'm thinking, scarlet fever today is no different than strep throat with a rash. But they say, 'Oh, scarlet fever! That's deadly!' And I'm like, it's the 21st century!'"

"So we, as physicians, look at disease in a very clinical way. But that's just my perspective," Tarini says. Meanwhile, say "scarlet fever" to a worried parent, and he or she hears something that's dire and dangerous, thanks to the stories they remember of Mary Ingalls' blindness or Beth March's death. "So I have to be attuned to that, and attuned to the fact that my diagnosis might be taken more out of proportion, and cause more anxiety, than I would think," she says.

It's nice to know someone is watching over the maladies of beloved characters in classic children's literature, but let's not neglect the fictional ones. Is anyone available to investigate Matthew Cuthbert's alleged "heart attack" in "Anne of Green Gables"?

Related: