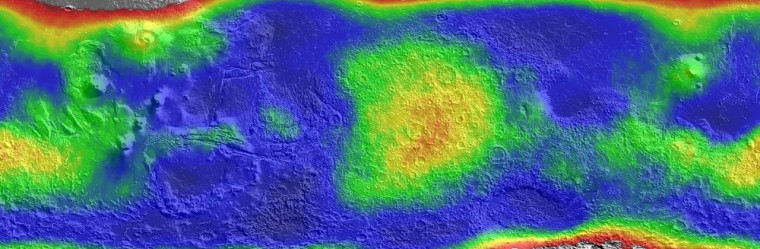

From the shoreline of an ancient salty sea to the bottoms of deep, flood-carved channels, Mars is scarred with geological signs that indicate liquid water once flowed on the its surface.

These findings, combined with the discovery of tiny, spherical "blueberries" and the detection of water ice in the planet's polar ice caps, have led scientists to scour the planet for signs of liquid water in recent years.

The elusive quarry has remained hidden, possibly because it may not exist for more than a fleeting second. Due to Mars' low temperatures and extremely low atmospheric pressure — less than a hundredth that of Earth — pure water evaporates from ice to gas so quickly that it skips the liquid phase.

But now, new research by a team of scientists at the University of Arkansas suggests that liquid water could persist for some time on Mars, so long as it is salty.

In the lab

Using a planetary environmental chamber — a tank that mimics the atmosphere, temperature, and pressure of other planets — the team exposed various concentrations of briny water to conditions that match Mars' colder, less pressurized environment. Based on these experiments, salty water, it seems, can exist as liquid on Mars.

"It was thought that any liquid on the surface would evaporate almost immediately," Julie Chittenden, a graduate student with the Arkansas Center for Space and Planetary Sciences, told Space.com. "These brine solutions enable water to stay liquid at colder temperatures. If you expose these brine solutions to cold temperatures, they can exist for a very long period of time."

While pure water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit (zero degrees Celsius), water mixed with sodium chloride and calcium chloride salts — the two salts used in these experiments — remains liquid down to minus-6 degrees and minus-58 degrees F (-21 and -50 degrees C) respectively.

Because salty water can exist as liquid at colder temperatures than pure water, it won't make the jump from ice to vapor as quickly, giving it a better chance of existing as liquid on the surface or just below it. Average Martian temperatures range between 193 below zero and 82 degrees F (-125 degrees and 28 degrees C) at various latitudes at different times during the day, and the salty test samples stayed liquid within the range.

The key

The key to staying liquid is to stave off evaporation, which occurs when the molecules in a liquid are excited to a state where they bump into each other until they break the liquid's surface and turn into gas. The best way to do prevent evaporation is to keep the molecules from becoming excited, and the best way to do this is to cool the liquid.

For example, a cup of water placed outside in the middle of summer will evaporate much more quickly than the same water on a midwinter day.

"Colder temperatures are what suppress evaporation," Chittenden said. "There's a huge decrease in the evaporation rate the colder it gets."

If liquid water is discovered, there is a good chance it may not sit right at the surface. NASA's Mars rover Opportunity discovered signs that salty liquid once existed only after digging a small trench in the Martian soil.

So, having completed this series of direct atmosphere contact experiments, Chittenden and her colleagues have begun investigating whether ice melts to liquid or jumps straight to gas when placed beneath a layer of simulated Mars soil in the planetary environmental chamber.

This research is detailed in an upcoming issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.