NUREMBERG, GERMANY — There is little physical evidence of the world-reverberating events that happened at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice 60 years ago.

Lawyers clutch their papers. Anxious defendants await their trials. The comings and goings have all the hallmarks of a local court in a regional city.

But the wooden benches in Courtroom 600 creak under the weight of history.

That's because few trials can compare in importance and historical impact to the International Military Tribunal which started here on Dec. 20, 1945, and convicted 18 leading Nazis of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

For Germany, the Nuremberg trials marked the end of the darkest chapter of its history and the beginning of a long process in which the country struggled to come to terms with its Nazi past.

For the rest of the world, it set the example for every succeeding effort to bring justice to perpetrators of war crimes, from Rwanda to the current prosecution of Saddam Hussein in Iraq.

A chance to achieve justice

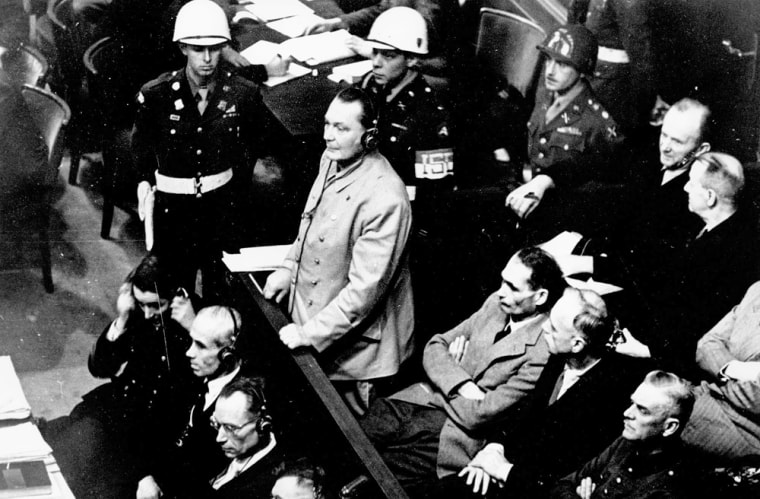

By the time the six-month tribunal began on November 20, 1945, Adolf Hitler and several other high-ranking Nazis had already committed suicide or disappeared, leaving 21 of the original 24 defendants identified by the allies to face charges. (One was deemed too ill to appear in court, resulting in 20 on the court’s benches.)

At the end of the remarkably rapid judicial process — which began just six months after the end of the war — 18 defendants were found guilty and three acquitted. Eleven of the guilty were sentenced to death and seven jailed.

The most senior of them, Herman Goering, the founder of the widely feared Gestapo, Hitler's secret police, committed suicide with a cyanide capsule just hours before he was due to be executed in 1946. The other ten were hanged.

In the wake of the trials, more than 5,000 people faced charges in so-called successor trials, which were lead by U.S. prosecutors. More than 800 people were sentenced to death in the tribunals; however, a total of only 469 war criminals were eventually executed.

In what became later East Germany, the Soviet occupiers were more ruthless in their de-Nazification process. Historians believe that up to 45,000 people were convicted, often without a proper trial. The Russians established camps where more than 120,000 Germans were detained and where some 756 executions took place.

Beginning so quickly after the end of the war, the prosecutions were invisible to most in the general German population, many of whom were still struggling to survive in cities, including Nuremberg, that were almost completely destroyed by Allied bombing. (In fact, Nuremberg was chosen as the site for the trials in part because its court building, located at the edge of the city, was one of the few undamaged legal facilities in the country.)

One who was aware was Arno Hamburger, a Jewish man who worked as an interpreter for the office of the chief counsel of war crimes in Nuremberg between 1946 and 1949 and lost many family members in the Holocaust. Now 82, he remembers the proceedings with mixed feelings.

"I did not feel satisfaction when I saw the Nazi doctors, Wehrmacht members and sympathizers stand trial," he said. "Instead, it was this momentum of achieving justice which prevailed," said Hamburger.

First international tribunal

And it was a form of justice that has continued, for the Nuremberg Trials were a milestone in judicial history.

"Nuremberg did not prevent other wars or war crimes, but it marked the birth of the practice of international law," said Professor Klaus Kastner from the University of Erlangen in Bavaria.

Perhaps the most important outgrowth of Nuremberg was the establishment in 1998 of the International Criminal Court in the Netherlands, created to ensure that the gravest international crimes do not go unpunished.

Most experts see Nuremberg as the initiation of international human rights trials, from the prosecution of former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic in The Hague to the Saddam Hussein trial which opened in Baghdad in October this year.

However, there are critical voices who say that today's war crime trials have not lived up to expectations, and do not achieve justice for millions affected by tyranny.

"The danger is that such trials become standalone spectacles that blame all crimes on one man and neither assign the guilt correctly nor cleanse the future," Simon Montefiore wrote in Britain's The Times newspaper.

In the trials, former dictators often rant at judges and ridicule the court. Others, such as former Bosnian Serb president Radovan Karadzic and Serb general Ratko Mladic, indicted in 1993, are still at large.

But, for Kastner, that’s all an important part of the process. "Because today's international tribunals strictly apply the rule of law, they are often long and complicated trials," he explained.

Dark chapter

Today, sixty years after the war, the ghosts of the country's Nazi history are still kept alive in Nuremberg, which is located north of Munich in the south-central part of the country and for most Germans is better known for its picturesque Christmas market.

"Nuremberg is the only German city which has persistently dealt with its Nazi past by establishing education centers and presenting human rights awards regularly," said Hamburger, who has been heading the local Jewish community since 1966.

In part, that may be due to Nuremberg’s dark legacy. In 1935, Hitler proclaimed his so called “Race Laws” in the city. The laws deprived German Jews of their rights of citizenship, giving them the status of "subjects" in Hitler's Third Reich, and opening the door to the systematic killing of millions of Jews.

Nuremberg also was the site where Hitler's National Socialist Party choreographed numerous rallies with up to 50,000 participants at a gigantic parade field between 1933 and 1938.

Rembering the trials

The Nuremberg ceremonies are among many 60th anniversaries marked this year, including end of World War II and the liberation of the deadly Nazi concentration camps.

At a panel discussion earlier this week, Arno Hamburger presented original documents from German archives which show how Nazi doctors conducted fiendish medical experiments on tens of thousand of Jews.

"Forget the history books," he argued. “Teachers must read from the original reports, which describe the indescribable — the full detail of Nazi atrocities and inhumanity."

On Sunday, historians and eyewitnesses will meet in Nuremberg to commemorate the trials that brought the culprits to justice.

Participants know that this will probably be the last anniversary at which eyewitnesses will be able to give a first-hand account of their experiences.

"It is important to keep the memories alive," said Benjamin Ferencz, 85, an American who was chief prosecutor at the follow-up trials.

"Important because we have not yet achieved the goal of making this world more humane and more peaceful," Ferencz said.