Ocean and so-called greenhouse gas levels are rising faster than they have for thousands of years, according to two sea and ice core studies published Thursday in the journal Science.

The ice core study examined tiny air bubbles trapped in ice to determine that the atmosphere has much more carbon dioxide — a gas that many scientists tie to global warming — than at any point during the last 650,000 years.

The ocean study found Earth’s sea levels have risen twice as fast in the past 150 years, signaling the impact of human activity on temperatures worldwide, researchers said.

Sea levels were rising by about 1 millimeter (0.04 inches) every year about 200 years ago and as far back as 5,000 years, geologists found from deep sediment samples from the New Jersey coastline. Since then, levels have risen by about 2 millimeters (0.08 inches) a year.

While the planet has been in a warmer period, driving cars and other activities that create carbon dioxide are having a clear impact, the Rutgers University-led team said.

“Half of the current rise ... was going on anyway. But that means half of what’s going on is not background. It’s human induced,” said Kenneth Miller, a geology professor at the New Jersey-based school who led the 15-year effort.

Carbon dioxide emissions come mainly from burning coal and other fossil fuels in power plants, factories and automobiles.

Data 100 million years old

Miller and his colleagues analyzed five 1,650-foot-deep samples to look for fossils, sediment types and variations in chemical composition, giving them data on the past 100 million years.

They also analyzed data from satellite, shoreline markers and by gauging ocean tides, among other measures.

“It allows us to understand the mechanisms of sea level change before humans intervened,” Miller said in an interview.

His team did not determine whether the rate is accelerating.

The research, funded mostly by the National Science Foundation, also found ocean levels were lower during the dinosaur era than previously thought. They were about 300 feet higher than now, not 800 feet as many geologists had thought, Miller said.

Measurements also showed that, while many scientists had thought polar ice caps did not exist before 15 million years ago, frozen water at the poles did form periodically.

“We believe the ice sheet was not around all the time. It was only around during cool snaps of the climate,” Miller said.

Ice study and carbon levels

In the ice core study, European researchers using three large samples of polar cap ice found carbon dioxide levels were stable until 200 years ago.

“Today’s rise is about 200 times faster than any rise recorded” in the samples, study author Thomas Stocker told Reuters.

The historic data “put the present rise of the last 200 years into a longer-term context,” he added.

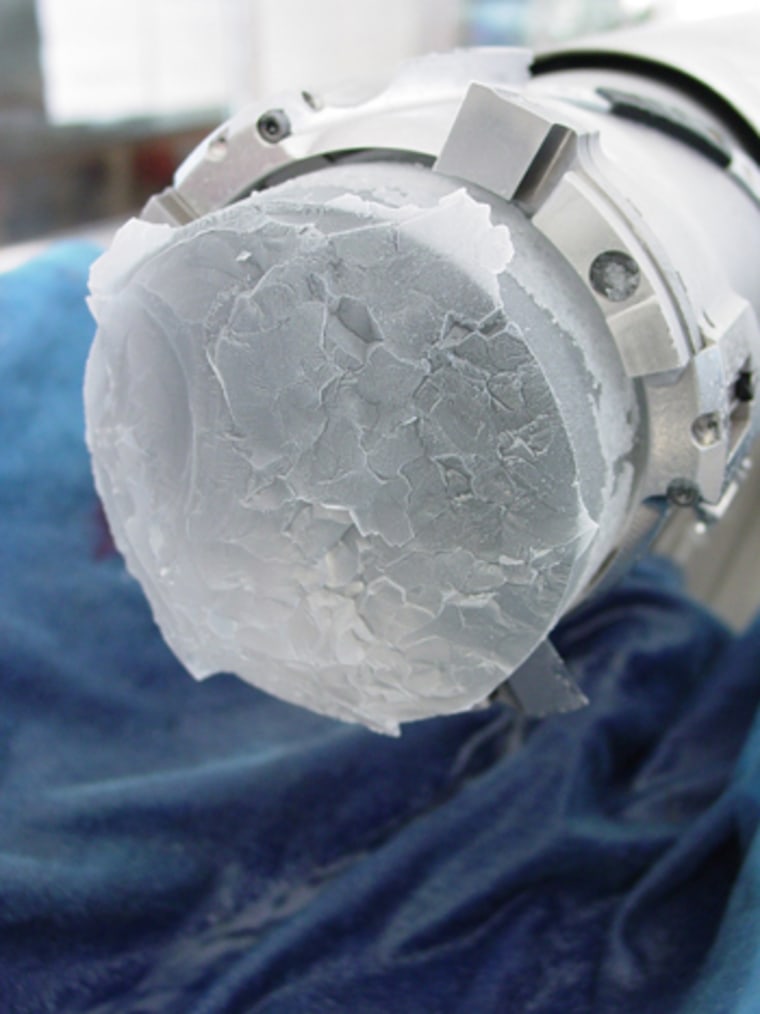

Trapped gas bubbles in the ice, drilled out from Antarctica depths of about 10,000 feet, provided scientists with information on Earth’s air up to 650,000 years ago.

Researchers participating in The European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica measured levels of carbon dioxide as well as methane and nitrous oxide -- two other gases known to affect the atmosphere’s protective ozone layer.

“The study does not directly address global warming. But what we provide is an important new baseline for the climate models with which we investigate global warming,” said Stocker, a professor of climate and environmental physics at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

Extending our understanding

The research promises to spur “dramatically improved understanding” of climate change, said geosciences specialist Edward Brook of Oregon State University.

Greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere as a result of natural but also fuel-burning processes. Those gases help trap solar heat, like the greenhouses for which they are named, resulting in a gradual warming of the planet.

The measurements of those gases are disturbing: Levels of carbon dioxide have climbed from 280 parts per million two centuries ago to 380 ppm today. Earth’s average temperature, meanwhile, increased about 1 degree Fahrenheit in recent decades, a relatively rapid rise. Many climate specialists warn that continued warming could have severe impacts, such as rising sea levels and changing rainfall patterns.

Skeptics sometimes dismiss the rise in greenhouse gases as part of a naturally fluctuating cycle. The new study provides ever-more definitive evidence countering that view, however.

How the bubbles help

Deep Antarctic ice encases tiny air bubbles formed when snowflakes fell over hundreds of thousands of years. Extracting the air allows a direct measurement of the atmosphere at past points in time, to determine the naturally fluctuating range.

A previous ice-core sample had traced greenhouse gases back about 440,000 years. This new sample, from East Antarctica, goes 210,000 years further back in time.

Researchers also compared the gas levels to the Antarctic temperature over that time period, covering eight cycles of alternating glacial or ice ages and warm periods. They found a stable pattern: Lower levels of gases during cold periods and higher levels during warm periods.

The bottom line, said Brook: “There’s no natural condition that we know about in a really long time where the greenhouse gas levels were anywhere near what they are now. And these studies tell us that there’s a strong relationship between temperature and greenhouse gases. Which logically leads you to the conclusion that maybe we should worry about temperature change in the future.”

A lengthening history of greenhouse gas concentrations should help climate specialists build better models about what the future might bring, Stocker said. It also may help answer additional questions such as how long ago humans started influencing greenhouse gas accumulations, and what impact other factors such as ocean currents play in the complexities of climate change.

Just a decade ago, scientists weren’t sure it was possible to trace greenhouse gas concentrations back so far in ice. Now, Brook is part of another international research team preparing to hunt an ice-core sample dating back a million years or more, hoping to reach eras when Earth’s temperature was significantly warmer.