It began as a mass e-mail in a certain Seattle office building on December’s first day.

A cold front was arriving! Snow! Ice! Untold inches for the city and surrounding area!

Within hours, the e-mail exchange called for an early dismissal and even generated a catchy headline, the kind that television news offers up for every tempest: “Snowstorm Katrina.”

A memo went out: “Please be aware that many or all of the staff will be leaving early today as snow and icy road conditions have hit Seattle.” A last call was sounded for overnight mail. Copy writers and bookkeepers turned into amateur meteorologists, e-mailing hourly weather updates to colleagues, and sending links to live weather cams.

The cautious drove home after lunch. The brave stayed behind.

And the snow never came. Not even an inch.

So goes the drill in an era when weather, however routine, is associated with peril. Be it a historic hurricane like Katrina or a run-of-the-mill snowstorm, weather is news — and not good news.

And it’s not just the banner headlines and screaming television graphics that attend each storm. Oil prices rise, the stores are cleared of bottled water and generators, milk and bread, and citizens become gently unglued as they engage in the interactive, televised conflict we used to call ... well, the weather.

‘The new war reporting’

“Television in particular has an affinity for action, suspense, drama, and danger, and ‘big weather’ delivers on all counts,” said Carol Wilder, chair of the Media Studies Department at The New School in New York.

“The past year of the tsunami and Katrina were larger than life stories and it was mother nature, not an enemy army, who was calling the shots. Reporters Anderson Cooper and Brian Williams delivered career-making performances. Weather reporting is the new war reporting, because war reporting has become just too dangerous for journalists.”

The rise of the weather as societal preoccupation, bogeyman and news-ratings staple is about several things, experts agree: the growing complexity and competitiveness of the media; our greatly improved ability to forecast the weather; the general climate of fear in which we live, which includes everything from terrorism to global warming.

This fear was bolstered by hurricanes Katrina and Rita and even by the Asian tsunami.

“There is a human tendency to generalize from one set of events to another,” said Barry Glassner, a professor of sociology at USC and the author of “The Culture of Fear: Why Americans are Afraid of the Wrong Things.” “If the recent hurricane season has been deadly, it follows that the winter season is going to be especially deadly even though they’re unrelated. There is a natural tendency to extrapolate.

“For example, if there is one heinous crime in a particular neighborhood or region, people imagine there will be more of them. If a friend has been diagnosed with a deadly disease, people imagine their common aches and pains as cancer.

“We are living in a period now when we are just as fearful about common dangers like bad weather as we are about unusually serious dangers like Category 4 hurricanes. We feel the world is out of control in many ways, politically and economically. So it makes sense to imagine the weather is out of control, too.”

Documentaries and forecasts

Our preoccupation with the weather and weather-related adventure is not limited to television news. It is reflected in the myriad of television documentary shows about tornado chasers, Coast Guard rescuers, and even crab-boat fishing off Alaska, which is exciting only because of the weather conditions the fishermen must endure.

But it is not only spectacular weather that gets our attention. While modern conveniences have insulated us from the effects of weather, advances in technology have also deepened our knowledge of it. And the more we can know, the more it seems we want to know.

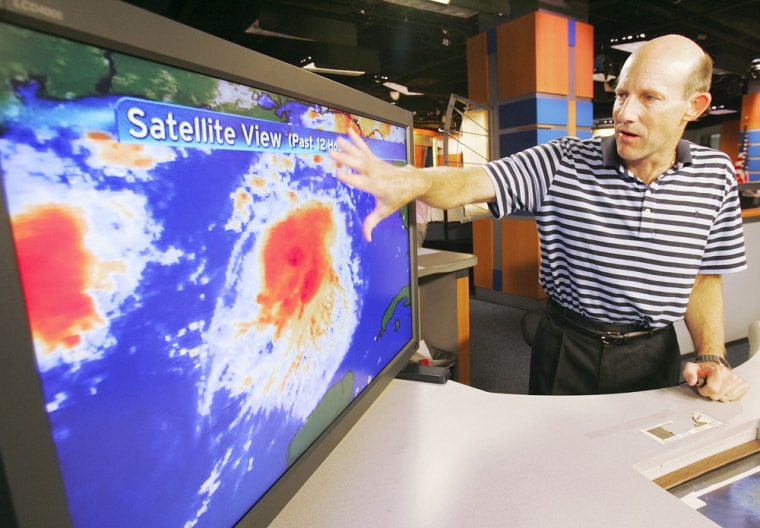

Five-day forecasts have now become 10-day forecasts, thanks to a sea change in radar, satellite, and computer technology in the 1980s and 1990s.

Until about 15 years ago, weather technology was of World War II vintage. Now more powerful radar can detect not just precipitation but wind speed and circulation, and from twice as far away. Powerful computers can calculate variables and give forecasts that are twice as accurate.

A five-day forecast today is about as reliable as a two-day forecast was in 1980. Weather can be predicted for very specific areas, and for very specific events, giving people the ability to plan their lives in great detail as it relates to the weather.

“I’d say if our depth of knowledge used to be 10 feet deep, now it’s 100,000 feet deep,” said Dan McCarthy, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Okla.

Weather Channel watched

The growth of the Weather Channel is also a reflection of our preoccupation. The network was launched in 1982 with much skepticism as one of cable television’s first channels.

“We heard it all the time: ’Weather? Twenty-four hours a day? Who’s going to watch that?”’ said Ray Ban, a meteorologist with the Weather Channel since its inception. “The sophistication of our programming was modest and I’m being generous. The difference (between now and then) is black and white.”

More than ever, weather is also literally money. Weather events shape stock prices and corporate profits, making it all the more newsworthy. Giant financial institutions like Merrill Lynch have their own meteorologists. Paul Janish works in Houston for Merrill Lynch’s global commodities unit, preparing weather data that becomes part of the company’s business strategies and decisions.

“Weather has gotten a lot more integrated into the overall business environment,” said Janish, who used to work for the National Weather Service. “Companies are looking into ways to leverage weather, to better manage their resources. With energy supplies so constrained, the weather is going to become a more integral part of the business world.”

In the business world, ice cream manufacturers and beverage companies wish for hot summers. Municipal budgets are made or busted on the number of snowstorms. Dry winters that produce little runoff in the summer can hurt companies that operate hydroelectric plants. The past hurricane season affected about 80 percent of the offshore gas infrastructure in the Gulf of Mexico.

All these events amount to billions of dollars and can be anticipated, in some part, by meteorologists, and dealt with using financial instruments like hedge funds, insurance policies, and energy futures.

For that reason, the demand for information about the weather will only grow — as will our fear and loathing.

Future technology

One of the next advancements in weather technology, McCarthy said, is a new form of radar called phased array radar. Current Doppler radar scans a storm every five to six minutes. Phased array radar can scan a storm every minute, giving forecasters a sort of live-time view of a storm. This kind of technology translates, among other things, into potentially being able to double the warning time of an approaching tornado.

It could save lives, and will certainly make for great television.

“It’s the awe of the weather,” Ban said. “It impacts most of what we do It’s an awesome event that we try to predict but it’s always bigger than we are. It creates inspiration and fascination. And there’s a gravitation towards the awe of it all.”

Errant calls

Even if sometimes the weather is more bluster than disaster.

In September, 1997, a Pacific hurricane, Nora, made its pass through Tucson, Ariz., in what, at first, promised to be a rare and dramatic event in the desert city but turned out to be a dud. A meteorologist from a local television station and his camera crew set up for a live shot on the third-floor balcony of the National Weather Service building in Tucson. He stood atop a garbage can and leaned away from the building so the wind would toss his hair.

All of this was witnessed by several amused weather service employees.

Their reaction was a mix of eye-rolling and empathy. Empathy because the weather experts all played some part in blowing the call. Eye-rolling because reporting the weather had come to this: standing on garbage cans as a way of attempting to stage and direct the weather as if it were some kind of disaster film.

“My first reaction was 'good grief,”’ said another meteorologist who witnessed the live shot. He did not want his name used lest he be viewed as poking fun of a colleague. “But at the same time, I was glad I wasn’t the one who had to get in front of the camera and talk about this hurricane we all predicted would be a big storm.”