Even if you never learned the difference between a triangle, a rectangle and a trapezoid, and you never used a ruler, a compass or a map, you would still do well on some basic geometry tests, according to a new study.

Using a series of nonverbal tests, scientists claim to have uncovered core knowledge of geometry in villagers from a remote region of the Amazon who have little schooling or experience with maps and speak a language without the mathematical language of geometry.

This research appears in Friday's issue of the journal Science, published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

For thousands of years, people have wondered if the basics of geometry came naturally to all humans or if they were something you had to learn through instruction or cultural experiences. According to Plato’s writings, Socrates attempted to determine how well an uneducated slave in a Greek household understood geometry, and eventually concluded that the slave’s soul “must have always possessed this knowledge.”

While a slave in a Greek household would have been introduced to aspects of geometry through the Greek language and culture, the Mundurukú villagers who participated in the new study did not have this head start. Nevertheless, the 14 Mundurukú children, as young as 6 years old, and the 30 adults who were quizzed by anthropologist Pierre Pica from Paris VIII University did well on the basic geometry test.

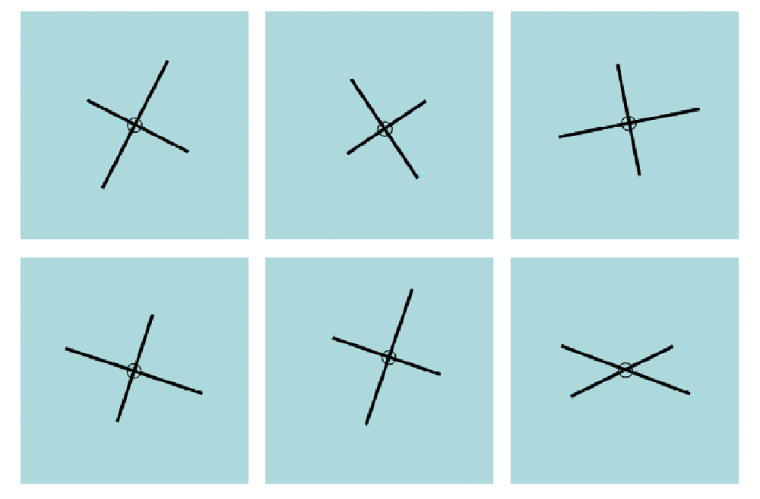

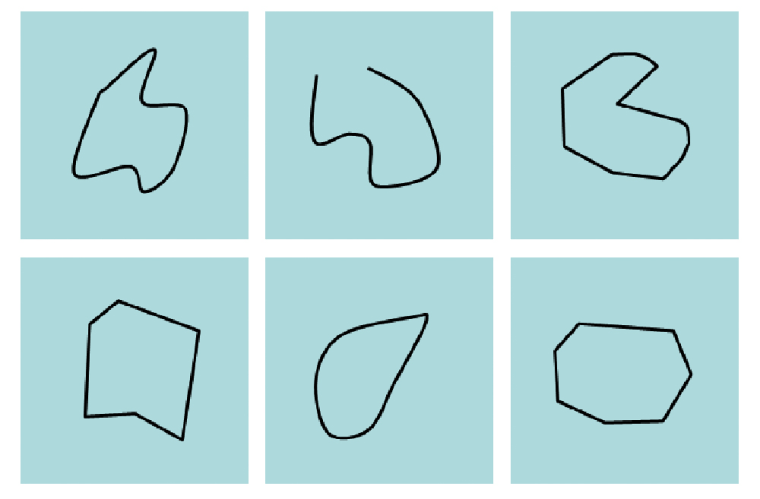

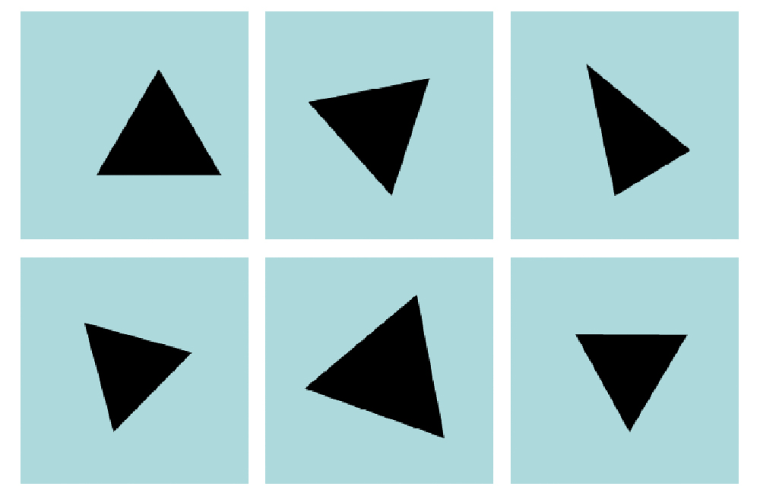

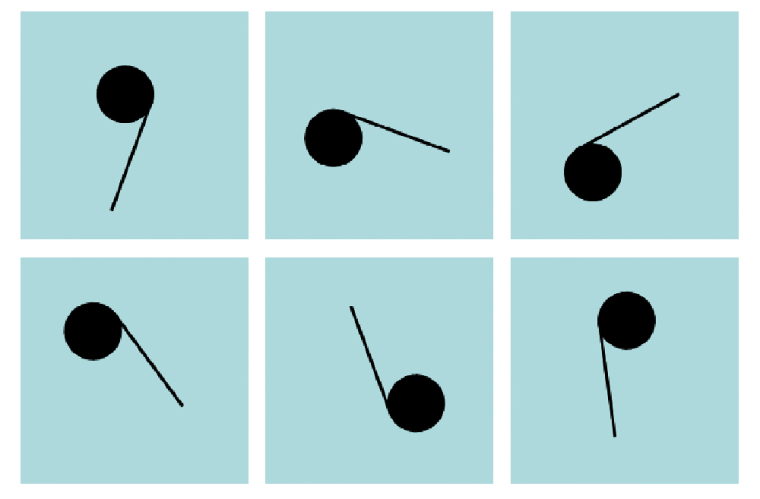

During the test, each participant was shown 43 sets of six images — and asked to choose the one “weird” or “odd” image out of each set of six. A correct answer required the person to choose the image that did not follow the same basic aspect of geometry illustrated in the other five images.

Four of the image sets used in the test are illustrated here.

In the first set, the bottom right box does not belong because the lines do not intersect at a 90-degree or right angle. Ninety three percent of the villagers picked out the non-right angle in this exercise.

The next set of images includes five closed shapes and one open shape.

77 percent of the Mundurukú participants picked out the open shape as the “weird” or “odd” image.

Of the triangles below, all have three sides of identical length, except one.

This set of images is supposed to test your sensitivity to differences in geometrical figures, despite the fact that you may not know the textbook difference between an equilateral and an isosceles triangle. Sixty-six percent of the villagers correctly chose the top right image as the odd one.

Finding the one “left-handed” image from five “right-handed” images below proved difficult, and the Mundurukú study participants did not do much better than chance.

Only 23 percent chose the bottom right as the weird or strange image.

Considering the 43 sets of images together, the Mundurukú villagers got about two-thirds of the answers right. Mundurukú children and adults did about as well as the 26 U.S. children the researchers tested. A group of 28 U.S. adults did better than any of the other groups. Nevertheless, the Mundurukú and U.S. participants had the most trouble with the same questions, which adds further evidence for the presence of core knowledge of geometry among the Mundurukú, according to the team led by cognitive scientist Stanislas Dehaene from the College de France and INSERM in Paris.

The word “geometry” comes from the Greek words for “Earth” and “measure.” Geometry was first used to measure and chart the length, area and shape of land surfaces.

To determine if the Mundurukú could use geometry for useful tasks, the researchers set up a map-reading test.

The scientists set out three containers in a right-angled or isosceles triangle in a large area. One container held a hidden object. After looking at a map representing the three containers, with one marked to indicate the object’s location, the subjects were asked to find the object.

Both Mundurukú children and adults did a good job reading the maps. To find the object, the participants had to translate the two-dimensional map into three dimensions; envision the maps information on a much larger scale; and locate the object based on the geometrical relationship of the three points, the authors say.

As in the first experiment, Mundurukú children and adults did about as well as American children, though not as well as educated American adults.

Debate continues

The new study described here is not likely to end the debate over just well and how universally humans understand geometry in the absence of schooling or exposure to words such as parallel, symmetry or right angle. Some scientists will continue to wonder how well the experiments actually test human understanding of geometry rather than visual perception abilities or intelligence.

Nevertheless, the authors of the new study conclude that they have uncovered evidence for a basic understanding of geometry among people without much formal education. Future research may clarify if humans are born with these intuitions or if we acquire them early in life.