It was created in 1926 by a Harvard professor intent on advancing knowledge of black Americans' role in America. It was expanded 50 years later to encompass the wider role of black participation in the national life.

But in the 80th anniversary year of what has become Black History Month, a long-standing debate has reawakened, with some African Americans questioning its pertinence in the 21st century.

Some see the February observance as a necessary check against the dominance of majority culture, and a vital reminder of everything African Americans have contributed to the nation.

For others, Black History Month is an anachronism that isolates the history of African Americans to a single month, reinforcing the very segregation the observance was intended to counteract.

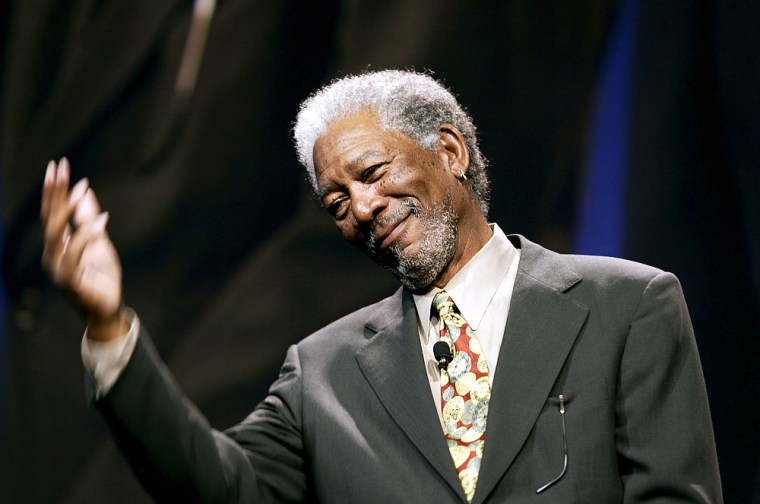

Actor revives argument

Comments made by Morgan Freeman in December have re-energized the debate, perhaps more impassioned than any since history professor Carter G. Woodson created the observance in 1926.

“You're going to relegate my history to a month?” Freeman said in an interview on CBS' “60 Minutes.” “I don't want a black history month. ... Black history is American history.”

Black History Month isn't the only such observance on the calendar. America's tributes to African American achievement also include the seven-day observance of Kwanzaa in December, the national Martin Luther King holiday in January and Black Music Month in June.

Those interviewed by MSNBC.com insisted that Black History Month still serves an important purpose; none went so far as to call for the observance’s outright elimination, but some suggested that America needs it because of continuing challenges of blacks in American society.

“The fact that it’s a necessity is a reflection of what's still going on in society,” said Mel Watkins, author of “On the Real Side,” a history of African American comedy. “It's necessary because African American history isn’t yet fully integrated into American history. The irony of it is that we still have to have a Black History Month to remind people that we have a history.”

Still, Watkins finds value in efforts to promote the observance. “You go to a bookstore [in February] and you'll see black books in the window other than those chosen by Oprah,” he said. “They won’t be stuck in the back somewhere in the African American section. That's one positive result of Black History Month.”

Seeing both sides

“I see both sides of the argument,” said David Dent, author and New York University journalism professor. “Black history is intrinsically American, so much broader than just one month. On one level, Black History Month does separate our history from the mainstream, and that shouldn’t be. But it reflects change in the way in which we study and discuss African American life and culture.

“It has become a tradition,“ said Dent, who wrote “In Search of Black America,” a study of the black middle class “But we have to seriously consider the question, ‘Is it time to move on?’”

Howard Dodson, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, disagreed.

“The notion that it’s outlived its usefulness betrays some ignorance of what its purpose was in the first place,” said Dodson, whose New York-based center is a leading source of information on black history.

“I find it interesting that no one suggests we stop studying white history on a year-round basis,” Dodson said. “If you follow the logic who say Black History Month has outlived its usefulness, they’re also saying that institutions like the Schomburg have outlived their usefulness.”

‘A little's better than nothing at all’

Kimberly Pollock, an educator in Washington state, agreed with Dodson.

“Sometimes what’s missing does as much damage as what’s misconstrued,” said Pollock, chairman of ethnic and cultural studies at Bellevue Community College, outside Seattle. “When you’re learning about history and the Founding Fathers and people who’ve great things, the fact that there are black people missing leads one to think they haven’t done great things,” she said.

“We need African American History Month; even a little time is better than nothing at all,” she said.

For another educator, Freeman's provocative comments rang true, and pointed to a need for blacks to be more widely depicted in American life without the customary attachment of ethnic descriptors.

“In the 21st century, Morgan Freeman is right,” said Andrew P. Jackson, president of the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. “By now we shouldn’t have to remind anyone of the contributions of black people.

"We should be past that, but we're not. Not until you can go to school and not have to take African American classes, not until you can go to classes and learn about Langston Hughes as part of American literature instead of African American literature.”