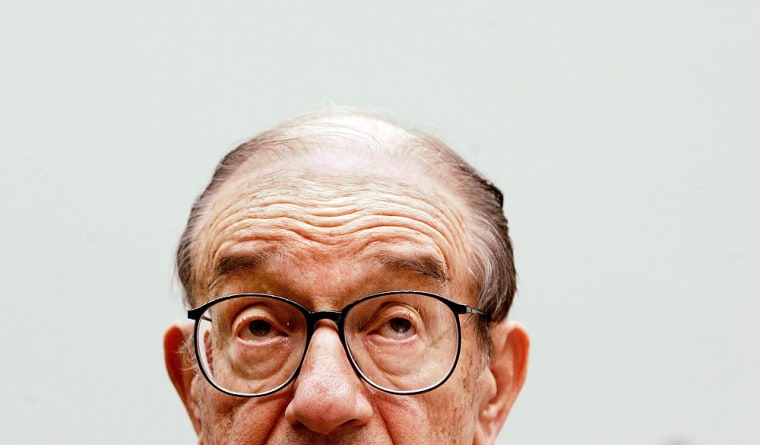

On June 7, 1995, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan attended an international banking conference in Seattle and gave a rare news conference. The economy was slowing, much as it is now, after a yearlong series of aggressive interest rate hikes.

Greenspan declared the economy was “sluggish” and said the economic slowdown was “quite pronounced.” This was before such an event would be routinely televised live, and wire service reporters scurried to the back of the room, whispering news alerts into their cell phones as Greenspan continued to speak.

Greenspan said the chance of a recession, while still small, had “edged up,” setting off another flurry of sometimes contradictory news alerts.

The next day, headline writers had their choice. “Greenspan Sees Chance of Recession,” trumpeted The New York Times, while the Washington Post focused on the positive, saying, “Recession is Unlikely, Greenspan Concludes.”

It was vintage Greenspan. The Fed chief was not trying to deceive the press and public, but Greenspan’s carefully couched, often ambiguous public statements left plenty of room for interpretation, especially at economic turning points. With his idiosyncratic method of forecasting, sifting through anecdotes, discussions with business leaders and reams of sometimes obscure economic data, Greenspan was working it out.

“He didn’t think about the economic world the way most of us do,” said Laurence Meyer of Macroeconomic Advisers, who served as a Fed governor from 1996 to 2002. “It made it difficult for him to communicate. His model was fundamentally different from everyone else’s. That is what we’ll miss.”

As Greenspan, 79, steps down Tuesday after an eventful 18-1/2 years at the Fed, it seems more than a little ironic that one of his lasting legacies will be a central bank that is far more “transparent” than it was when he took office. After all Greenspan himself was hardly a model of personal clarity.

But if Greenspan could be ambiguous in his public comments, his iron grip on Fed policy allowed him to move steadily toward more open communication with investors. When Greenspan took over, the Fed did not even publicly announce its interest-rate decisions, although traders figured it out quickly when a change was made.

By contrast in recent years the Fed generally has telegraphed its moves well in advance and rarely surprised financial markets. One notable exception came in early January 2001 when the central bank began cutting rates after the economy showed clear signs of slowing.

In the 1995 case, not only was a recession avoided, but the economy went on a tear, adding 3 million jobs a year in the last four years of the decade, compared with about 2 million jobs annually over the past two years.

In fact, a little more than a year later the economy was growing so rapidly that many central bank officials worried about inflation heating up and wanted to cool things down by raising interest rates. That is when Greenspan came up with one of his landmark theories, arguing that the economy could continue growing without fueling inflation because of a previously unidentified increase in productivity.

Virtually all economists recognize now that Greenspan was correct, and that massive spending on information technology in the 1980s and ’90s finally had begun to pay benefits. Companies were able to provide more goods and services per employee, limiting the wage inflation that is one of the Fed’s biggest concerns.

Greenspan became a very public believer in the technology advances that fueled the dot-com boom and the ensuing stock market run-up, leaving himself open to criticism that he let the boom go on too long. The criticism persisted even after Greenspan famously cautioned in a 1996 dinner speech that “irrational exuberance” may have caused investors to to bid up stock values beyond their intrinsic value. Stock prices fell over the next several sessions but quickly resumed their steady march upward until the decade’s great bull market peaked in March 2000 and then collapsed.

But the recession that followed in 2001, while painful for the tens of thousands of people who lost jobs, was one of the briefest and mildest of the postwar era. Consumer inflation, stamped out under Greenspan’s predecessor Paul Volcker, is still barely a concern nearly five years into the current expansion.

Certainly Greenspan has his detractors. The nation’s record and rising trade deficit requires constant infusions of global capital to keep long-term interest rates low, an imbalance that could lead to a crisis, Volcker and others believe. Some economists say Greenspan was too sanguine about rising household debt, fueled in part by rapidly rising home values that could be prove to be another stock market-style bubble.

But looking back on his years in office, economists on Wall Street, the private sector and academia almost unanimously give Greenspan top marks, often describing him as the greatest central banker ever.

“There is no doubt truth to the idea that the stable economy we have enjoyed in recent years — in recent decades — has reduced the perception of risk and encouraged people to take riskier positions,” said Princeton University economist Alan Blinder, who served on the Fed board from 1994 to 1996.

“But that is a measure of success, not failure,” he said. “When the the road is built better, paved more smoothly and has better guardrails, people drive faster. That’s not irrational.”

The road was not always quite so smooth.

An economic consultant who advised Presidents Nixon and Ford, Greenspan was appointed to be Fed chairman by President Reagan and took office Aug. 11, 1987. Just two months later, on Oct. 19, the stock market suffered the worst single-day loss in its history. The Dow Jones industrial average shed 508 points or 22.6 percent on that “Black Monday” in a selloff blamed at least in part on computerized program trading in an increasingly interdependent global market.

The selling continued the following day, and Greenspan has been credited with helping ensure the markets remained open even as the specialist system came close to a potentially disastrous lockup.

Unlike the catastrophic market crash of 1929, which heralded the beginning of a global depression, the effects of the 1987 crash were relatively short-lived. By the end of the year, the stock market had stabilized, and within two years the Dow had surpassed its pre-crash peak.

Crisis shook the economy again in 1998, when Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt, triggering a global financial crisis and the near-collapse of a giant private investment fund known as Long-Term Capital Management.

In short order, the Greenspan-led Fed cut interest rates three times to maintain liquidity in global financial markets. Meanwhile William McDonough, president of the New York Fed, called together officials of Wall Street's leading investment banks to engineer a private bailout of Long-Term Capital.

Perhaps the biggest threat of all to the global financial system came Sept. 11, 2001, when terrorists struck the heart of New York’s financial district, bringing down the twin towers of the World Trade Center and killing nearly 3,000 people.

With the stock market closed for a week and the system of interbank payments physically disrupted, the Fed stepped in quickly to provide liquidity to the financial system. Interest rates were lowered dramatically in the weeks after Sept. 11, and the Fed took other measures that were credited with allowing most of the nation’s commercial systems to continue operating normally at a highly uncertain time.

Greenspan seems sensitive to charges that the Fed was slow to “take away the punch bowl” after the record postwar expansion of the 1990s and has argued that it was almost impossible to determine at the time that a bubble was in fact forming. “The notion that a well-timed incremental tightening could have been calibrated to prevent the late 1990s bubble is almost surely an illusion,” he said in a 2002 speech in Jackson Hole, Wyo.

Similarly, Greenspan has left at least a paper trail in his defense against charges that he allowed the housing bubble to grow unfettered. At a Fed-sponsored conference on his legacy in Jackson Hole, Wyo., last year, Greenspan reflected on rising home values and cautioned that “history has not dealt kindly with the aftermath of protracted periods of low risk premiums.”

And in one of the very few research studies that he has co-authored in his nearly two decades at the Fed, Greenspan last year warned that consumers have become heavily dependent on drawing equity out of their homes to fuel spending, an economic driver that is could be endangered as mortgage rates rise.

He has warned of “froth” in some local housing markets but has stopped short of concluding that a market slowdown will severely affect the national economy.