Last week saw what has become a tradition for Apple enthusiasts: following the usual deep-secret build-up, Steve Jobs showed off the latest Mac mini onstage in Cupertino, Calif., as breathless tech bloggers filed minute-by-minute updates. Over the years, Jobs has become a master of the technology art form known as the “demo.” In fact, if Steve hadn’t had that knack for computers, he almost certainly could have made an alternative fortune selling kitchen gadgets on late-night cable television.

The power of the demo should never be underestimated: one changed my career, back in the mid-Eighties. Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates invited a bunch of writers, publishers and technologists to Redmond, Wash., for a conference called “The New Papyrus,” to extol the virtues of the newly-developed CD-ROM as a vehicle for interactive content. The highpoint of the conference was his presentation of the interactive encyclopedia that the CD-ROM would make possible. It was an astounding demo to witness back in 1986: on the entry for Martin Luther King Jr., you could not only see photos and read text, you could hear the “I Have a Dream” speech and actually view video as well.

I was sold, and immediately decided to abandon the paper and ink world and move into interactive multimedia. But what I didn’t know was that Bill’s demo was radically distant from anything that was even vaguely possible with CD-ROMs at the time. I ended up slogging through years of trying desperately to get video and audio to work on a whole parade of now-defunct devices and software. And ironically, about ten years later, still trying to get multimedia right, I ran into the guy who had programmed Gates’ interactive encyclopedia back at the conference that changed my life. “Oh sure,” he said casually, “I remember that demo. An AT&T minicomputer, running behind the curtain.”

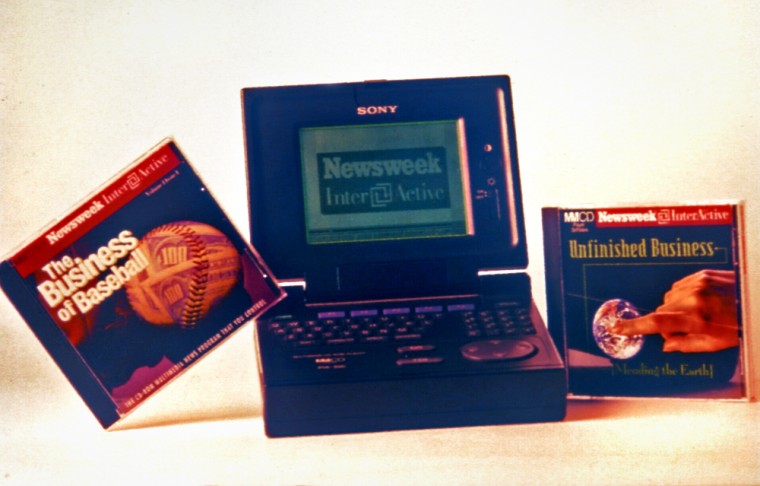

But by then, I was already deep into the world of demos myself. It started with an interactive CD-ROM version of Newsweek, complete with audio and video, that ran on an early Sony product with an LCD screen that looked a lot like today’s portable DVD players. The little multimedia player was a very cool device and far ahead of its time — but it was also, unfortunately, as slow as molasses. When you started to play a disk it seemed to take decades for the Newsweek logo to appear on screen, and then another geologic era before the announcer said “Welcome to Newsweek Interactive!”

I soon discovered, however, that you could actually start up the disk, wait through the interminable loading period, and then go back to the beginning of the program. As long as you didn’t turn the power off, the introductory segment would then start to play almost instantly. Thus, as I went around the country demonstrating the device to reporters or on televisions shows, I always made certain that I’d performed this little sleight-of-hand before the presentation began. By the unwritten code of the demo, this wasn’t lying — I was simply showing the machine to its best advantage.

As we continued to put Newsweek content onto new devices and services, my demo skills improved. No matter how buggy the software or Web site, I would spend hours plotting a path through the product that worked perfectly once the cameras were rolling or the reporter or audience was watching. Again, I didn’t consider this dishonest. I knew these bugs were simply blemishes that would soon disappear. It was a proud moment when a software developer introduced me to a colleague with this accolade: “Michael can demo a dead dog.”

I had certain standards: I always used the actual program running on the hardware for which it was intended. But not all demos follow those rules. In the mid-Nineties I attended an advertising convention to show off the latest version of online Newsweek, and arranged for a telephone line to log on for my demonstration. Even though I used a special number for the very latest 14.4 K connection, the demo was still excruciatingly slow, as was most online content in those days. But after my presentation, a guy from a certain competing newsweekly came up to do his demo of their online version, and ignored the telephone line entirely. He had stored their entire site on a hard drive, so his demo was, by comparison, lightning fast. Back then, most advertising executives didn’t know a modem from a motorboat, so my rival won that bake-off quite handily.

My own demo career taught me always to look behind the curtain. A couple of years later I was at a meeting of American newspaper editors in San Francisco, whose program included a speech by Larry Ellison, the renowned and ruthless head of the software superpower Oracle. The always-persuasive Ellison was demonstrating his then-newest brainstorm: the so-called “network” computer that contained relatively little software and instead received all its programming over the Internet.

After extolling the virtues of the new computer at length — low cost, constantly updated software, infinite storage ability on the network — Ellison did his demo, prefacing it by saying he was using an ordinary telephone line to connect to the Internet. The demo was dramatic, culminating in a full-motion color video of an Apollo mission blast-off. The audience, of course, was wowed, especially to see such great video coming off a mere telephone line. One tech-savvy person in the audience stood up and asked again if the connection was just a telephone line, and the mogul said yes—this was one of the great strengths of the network computer.

The nation’s newspaper editors went away convinced they had seen the future of computing — none of their home computers could produce video like that. I waited until Ellison left and the auditorium cleared, and then went up on stage where the Oracle techies were taking down the demo. “Great demo,” I said. “Was this really just using a telephone line?”

“Sort of,” said the techie. “Six paired ISDN lines running at 768K.” (Translation: The hookup was to a phone line as a nitro-fuelled dragster is to a VW bug.)

The demo is so much a part of the tech world that it even figures in a classic programmer’s joke. Bill Gates passes away and at the pearly gates St. Peter tells him that he can choose between going to Heaven or Hell. Gates asks if he can see them both before he decides and St. Peter agrees. First he shows Gates a glimpse of Heaven: a bland, boring suburb of identical tract houses and white-bread inhabitants. Then Hell: an incredible hackers’ paradise equipped with the latest high-speed computers, soda and chip machines at every corner and the hottest software available for free. Gates says, it sounds odd, but I think I’ll take Hell. St. Peter snaps his fingers and suddenly Gates is surrounded by fire and brimstone and a little demon is poking him with a pitchfork. “Wait a minute,” Gates shouts, “where are all the computers?” The little demon looks puzzled for a moment and then smiles. “Ah,” he says, “you must have seen our demo.”