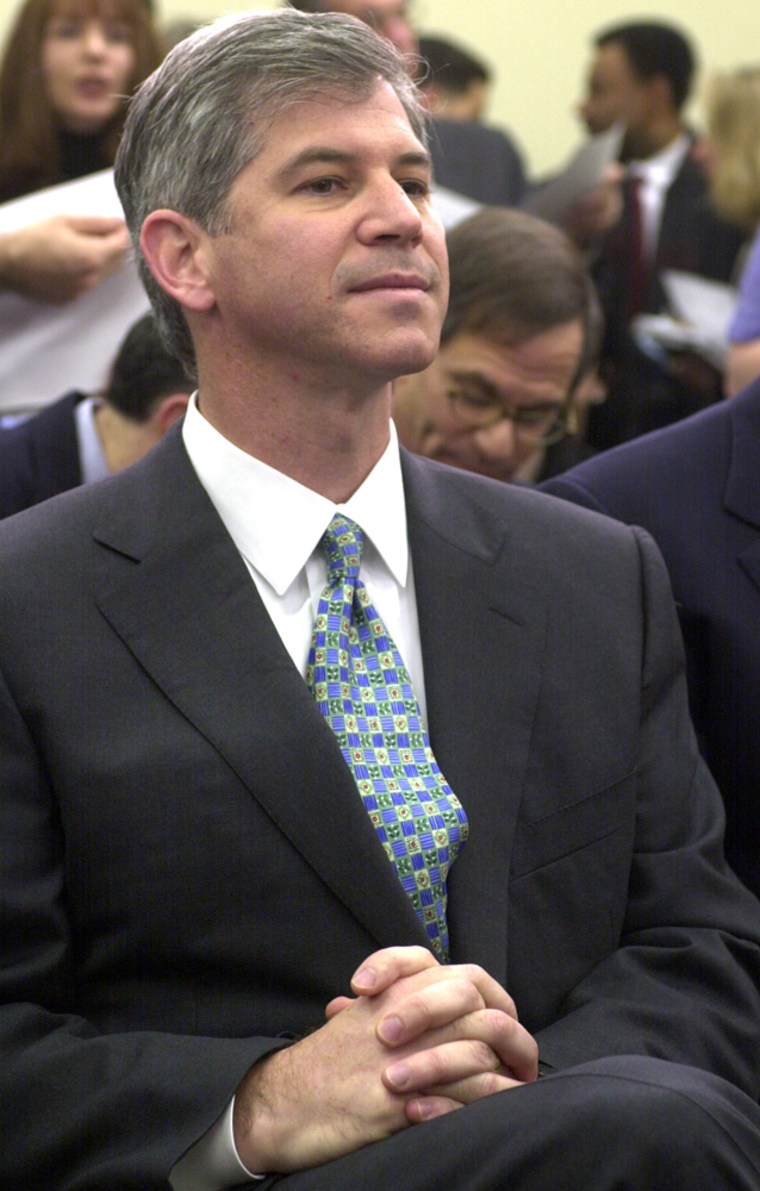

Andrew Fastow, the purported financial whiz whose web of financial machinations helped fuel Enron Corp.’s crash, is about to break his silence.

And after years of being labeled as the crook who brought down Enron — most notably by company founder Kenneth Lay — he’s ready to throw some punches in his much-anticipated courtroom faceoff with Lay and former Chief Executive Jeffrey Skilling in their fraud and conspiracy trial, Fastow’s longtime spokesman said.

“He’s felt from the start that he was the scapegoat,” said Gordon Andrew, who noted he hasn’t talked to Fastow for months. “If he’s going down, they’re going down with him, and this is his moment. I think Andy will say whatever he has to to bring these two guys down with him.”

But Fastow, who has a hair-trigger temper, could be a wild card for prosecutors and unlikable to jurors, Andrew said.

“He’s been stewing for quite a while,” the spokesman said.

Fastow, 44, is on deck to take the spotlight in the sixth week of his former bosses’ trial, as early as Tuesday. Prosecutors anticipate questioning him for less than a day, and then Lay and Skilling’s multimillion-dollar legal teams get their turn.

A string of witnesses last week bruised the defense and set the stage for his court appearance, most notably Kevin Hannon, a former broadband executive, who said Skilling told several top executives — including Lay — “They’re on to us” during a discussion of an analyst’s criticism of partnerships Fastow ran that conducted deals with Enron.

Lay and Skilling say the LJM partnerships were proper and received all necessary approvals from lawyers, accountants and Enron’s board.

Fastow, who had closer proximity to Lay and Skilling than most, could inflict more damage on the defense.

“It’s going to be interesting to hear from Andy Fastow and to see the level of contrition that he brings to his testimony,” said Robert Mintz, a former federal prosecutor and a white-collar defense attorney with McCarter & English.

“Prosecutors certainly want him to be credible,” Mintz said. “It if looks like he’s shifting too much blame onto others, that could backfire.”

Fastow was initially indicted in October 2002 on what grew to 98 criminal counts, including fraud, conspiracy, money laundering and cheating on his taxes for engineering myriad schemes to hide Enron debt, inflate profits and skim millions of dollars for himself on the side. He came out fighting, claiming through his attorneys that Lay, Skilling, the board and Enron’s accountants knew what he did and approved his work.

“They had a failing business and his job was to put his finger in the dike,” Andrew said.

Fastow remained defiant in May 2003 when the government obtained an indictment against his wife, Lea, for conspiracy and tax crimes for helping him hide ill-gotten gains.

In January 2004, at her urging, Fastow pleaded guilty to two counts of conspiracy in a deal that was contingent upon prosecutors striking a plea agreement with his wife. She eventually pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor tax crime and last July finished serving a year in Houston’s downtown federal prison.

Fastow then gave prosecutors ammunition to get to the top of Enron’s corporate ladder with indictments against Lay and Skilling.

Lay has repeatedly targeted Fastow as a criminal who betrayed his trust.

“It looks like Fastow was the mastermind of all of it,” Lay told The Associated Press days after he was indicted in July 2004. “And again, he apparently did a pretty good job of selecting those he wanted involved in it. But we’re more likely to think there was bad activity going on very close to him than anywhere else in the company.”

Fastow’s testimony could skewer Lay and Skilling’s insistence that there was no fraud at Enron beyond Fastow and two others who stole money from the company.

So far, the defense teams have mercilessly sought to portray government cooperators as mouthpieces for prosecutors who will say anything in hopes of getting lenient punishments.

But Fastow agreed up front to serve a decade for his crimes. He can be prosecuted for the remaining 96 criminal counts if the government is displeased with his help.

“The defense can argue that he gets 10 years not if he tells the truth, but if he says what the government wants to hear” Mintz said.

Yet for all the hype about Fastow, another of the 16-ex-Enron executives who have pleaded guilty to crimes has less baggage.

Former Enron treasurer Ben Glisan Jr. is serving a five-year sentence for conspiracy for developing the Raptors, or four fragile financial structures backed by Enron stock that were used to lock in the energy company’s gains from asset values or investments and keep hundreds of millions of dollars in debt off the energy company’s books. Allegations against Skilling include that he knew the Raptors were wrongly treated as independent of Enron and that they were used to avoid public disclosure of decreases in asset values.

Glisan didn’t initially cooperate with prosecutors and went straight to prison after pleading guilty in September 2003. If he testifies against Lay and Skilling as expected, he gains nothing because the one-year window for prosecutors to recommend that his sentence be shortened ended a year after he entered his plea.

Glisan, wearing a green prison-issue jumpsuit and blue canvas shoes, testified during the 2004 fraud and conspiracy trial of four former Merrill Lynch & Co. executives and two former midlevel Enron executives accused of helping push through a sham deal so Enron could appear to meet earnings targets. The Merrill executives and former Enron finance executive Dan Boyle were convicted.

Boyle and Glisan are incarcerated at a low-security men’s federal lockup in Beaumont, about 70 miles east of Houston.

During his testimony, Glisan declined to name anyone as having corrupted him, even Fastow, who hand-picked him as treasurer. Glisan was fired a month before Enron sought bankruptcy protection because he invested $5,800 in a Fastow deal and pocketed a $1 million profit days later.

“We’re all responsible for our own actions and I’m taking responsibility for mine,” he told jurors.

Fastow joined Enron in 1990, the same year as Skilling. He was among Skilling’s first hires.

He rose to CFO in 1998, a year after his wife, who rose to assistant treasurer, resigned to be a full-time mother to their two young sons. In 1999 he created the first of the two LJM partnerships — names with initials of his wife and sons, Jeffrey and Matthew. Enron’s board waived a conflict of interest policy to allow him to run entities that conducted deals with his main employer.

Skilling faces 31 counts of fraud, conspiracy, insider trading and lying to auditors, while Lay faces seven counts of fraud and conspiracy. If convicted, both could serve decades in prison. Only Skilling faces allegations of improper stock sales.