• May 5, 2006 |

X-woman trains for space: Iranian-born entrepreneur Anousheh Ansari, the woman behind the Ansari X Prize's $10 million purse, has surfaced in Russia as a backup cosmonaut for September's flight to the international space station — and it's likely that she'll eventually realize her dream of going into space.

If Ansari were to fly this fall, she would be the first woman to pay her own way into outer space. That wouldn't happen unless Japanese millionaire Daisuke ("Dice-K") Enomoto were to bow out for some reason. Enomoto is paying an estimated $20 million for a weeklong visit to the international space station — and by all reports, his training is going well.

But the fact that Ansari is going through the training puts her in good position for a later Soyuz flight. Such tours are arranged by Virginia-based Space Adventures, which already has helped put three millionaires (Dennis Tito, Mark Shuttleworth and Greg Olsen) into orbit.

"There are a lot of people in the queue," Eric Anderson, Space Adventures' chief executive officer, said today at the International Space Development Conference in Los Angeles. After Enomoto, the next person in the queue is software billionaire Charles Simonyi, who is slated to go on a Soyuz flight as early as next spring.

So where does Ansari stand in the queue? There's not much information available. Back in March, Space Adventures pooh-poohed reports that Ansari would be Enomoto's backup — and even today, Anderson shied away from confirming the Russian reports about her status. However, he seemed to signal that Ansari fully intended to follow through with a spaceflight in the future.

"I wouldn't want to spend my time as a backup if I couldn't fly eventually," he told me. (Check out this Russian-language gallery of Ansari's activities in Russia last week.)

Ansari is part of a family that made millions in the telecommunications industry. She and her brother-in-law, Amir Ansari, reportedly gave the X Prize Foundation something in the neighborhood of $1 million for use as seed money to buy a $10 million "hole-in-one" insurance policy backing up the X Prize pledge. The team behind the SpaceShipOne rocket plane satisfied the conditions for a payoff in October 2004, before the policy's deadline.

At the time, the Ansaris made no secret about their dreams of spaceflight. Yet another space connection was forged this February, when Space Adventures announced that the Ansaris' Prodea venture fund would be investing in the development of suborbital spacecraft in Russia.

Updates about that spacecraft, known as the Explorer, may be coming out of Russia sometime in the next couple of months.

Anderson has emphasized that neither Space Adventures nor Prodea would actually be operating the Explorers. That would be up to partners in the two locales that Anderson has identified as spaceport sites: Ras al-Khaimah in the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore. Today, Anderson indicated that the financing is in place for the Arab spaceport, but "the Singapore project has not been fully funded yet."

And then there's Space Adventures' big-ticket item: a $100 million package that would give the buyer a Russian ride around the moon and back. Anderson said the offer has generated more interest than he expected — and who knows? Perhaps someone will come up with the money. Greg Olsen, who shared the stage with Anderson at a presentation this morning, said he was intrigued.

"This moon thing really excites me," said Olsen, a scientist/entrepreneur who made millions when the company he helped start up was sold. "But I guess I'll have to go out and sell another company before I do that."

• May 5, 2006 |

Weekend field trips on the World Wide Web:

• 'Nova' on PBS: 'Hitler's Sunken Secret'• The Economist: One qubit at a time• Discovery.com: Survival of the fittest royalty

• Astronomy: Catch the year's brightest comet

• May 5, 2006 |

The future of space sails: Solar-sail technology has been promoted as the only currently conceivable way to propel spacecraft to other star systems — but it turns out that the concept could get an extra push from less starry-eyed initiatives, such as space weather prediction and communication networks for Antarctica and the moon.

The concept has been around for years: Engineers figure that the pressure of light photons from the sun, or perhaps a tightly focused laser beam, could push against a gossamer sail to drive it through space much as a sailboat is driven across a lake. Russia and Japan have tested sail deployment systems in orbit, and last year's unsuccessful Cosmos 1 mission was aimed at demonstrating how a solar sail could guide a spacecraft in orbit.

At this week's International Space Development Conference in Los Angeles, Planetary Society executive director Louis Friedman told attendees that his nonprofit group was raising funds to stage another solar-sail demonstration.

If the mission comes together, Friedman said he'd avoid using the Russian submarine-launched Volna rocked, which figured in Cosmos 1's failure. Instead, the society is considering signing on for a Russian Soyuz-Fregat or Cosmos 3M rocket launch, he said.

"We're determined to try again," Friedman said.

Meanwhile, NASA has been talking about setting up a solar-sail competition as part of its Centennial Challenges program (PDF file). And if solar sails are shown to work, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says it would be interested in using them on future satellites.

NOAA's interest springs from the agency's plan for next-generation sun-watching satellites. Space storms — that is, outbursts of electrically charged particles from the sun — can have a punishing effect on Earth-orbiting satellites and electrical power grids, and NOAA's Space Environment Center has the job of alerting authorities to the onset of such storms in advance.

The agency's space weather forecasters currently rely on solar-wind data from NASA's Advanced Composition Explorer, which orbits a gravitational balance point called L1, about 1 million miles from Earth. The problem is, no one knows how much longer ACE's sensors will hold up. So NOAA commissioned two industry groups to come up with ideas for how to replace ACE once it goes.

One group, led by Lockheed Martin Space Systems, suggested that NOAA acquire a mothballed satellite from NASA (variously known as Triana, GoreSat or the Deep Space Climate Observatory), giving it an upgrade and launching it to take ACE's place at L1.

The other group was led by Houston-based Space Services Inc. "We were the 'how-do-you-do-it-in-a-nontraditional-way' team," Charles Chafer, the company's chief executive officer, told me this week. His team proposed leaving the job of putting up a satellite to the private sector, with NOAA purchasing solar-wind data as an "anchor tenant" for the project.

The team also suggested using a solar sail instead of chemical thrusters to keep the satellite in the proper position at L1. "What would it look like if we were to build and fly a microsatellite, and ultimately use advanced solar-sail technology to station-keep?" Chafer said. "We spent the majority of the effort looking at the business case."

Chafer said the key was to come up with multiple applications for the satellite platform: For example, the National Science Foundation could use it to beef up communication links to its South Pole research station. NASA could use it as a link to a future base at the lunar south pole, which is thought to be one of the most promising areas for settlement. An Earth-facing camera could send back continuous sunlit imagery of our own planet, as Triana would have done.

It would also be worth looking into NASA's solar-sail competition as a sweetener for the project, Chafer said, although the proposed purse of $2.5 million to $5 million is "a small amount of money."

The first microsatellite could conceivably be launched in mid-2009, kicking off a series of missions that would gradually phase in the solar-sail technology, Chafer said.

NOAA officials have been digesting the reports from the two teams, and are leaning toward "trying to combine them if possible," according to Pat Mulligan, who heads the space weather requirements team at NOAA's National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service.

Under this "best-of-both-worlds" scenario, the agency would try to work out a deal with NASA for the Deep Space Climate Observatory, and develop a private-public partnership to upgrade and operate the satellite. Mulligan emphasized that NASA still had to weigh in on the plan.

But what about the solar sail? "We retain an interest in that capability," Mulligan said.

• May 5, 2006 |

Scientific smorgasbord on the Web:

• Nature: Cyclic universe could explain cosmic balancing act• Scientific American: Android science

• Myrtle Beach Online: Intelligent-design think tank struggling

• CSI announces space station cargo agreement

• May 3, 2006 |

Inside the rocket factory: As you tour the headquarters of Space Exploration Technologies Corp., or SpaceX, you might not always get the feeling that you're on the frontier of the commercialization of the final frontier.

From the outside, SpaceX's headquarters look like a collection of nondescript warehouses — or even, say, DVD duplication shops — just a few minutes' drive from Los Angeles International Airport. Once you're inside, you get more of that rocket factory feel, with metal domes and circlets and tubes and frames and engines scattered over the floors of four buildings. But the actual rocket firings take place elsewhere, at a Texas test facility.

It's really the words of the tour guide, 34-year-old millionaire founder Elon Musk, that bring your focus to the reason why he started the company four years ago. It's not just to bend metal — but more fundamentally, to further our status as a spacefaring civilization. "Humanity, as life's agent, has the ability to extend life to another planet," he told our tour group.

The grand sweep of Musk's ambitions complemented the gee-whiz appeal of today's tour, which was organized under the auspices of this week's International Space Development Conference in Los Angeles. About two dozen of us conference attendees converged on SpaceX's parking lot, walked inside and gawked as Musk pointed out the attractions:

- The 12-foot-high circlets of aluminum that are being welded together for the first stage of SpaceX's future Falcon 9 rocket. Someday, versions of the finished 174-foot-long rocket just might be sending passengers into orbit. "You're really seeing the very first barrel sections of the Falcon 9 vehicle," Musk told us.

- The prototype for the Dragon capsule those passengers might ride. The rounded metal cone stood upright in a corner of the shop floor, looking like a two-story playhouse. We took turns climbing up a metal stairway to peer inside the hatch at five empty seats, surrounded by hardware and the dark metal hull. The Dragon concept has been proposed to NASA as a means of getting back and forth between Earth and the international space station. "If SpaceX ends up winning that contract ... we would actually design a larger version of this," Musk said.

- Rocket engines in various stages of assembly, and yards-long tubes that will be put together to create SpaceX's next Falcon 1 rocket. This rocket is slated for launch in September or October from Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific, Musk told us.

- Perhaps most poignantly, the junk recovered from the first Falcon 1 launch in March — a test mission that went awry due to a fuel leak. The remains were spread across several tables set up in SpaceX's propulsion building. There were carefully labeled hoses, bunged-up shards of metal — and even FalconSat 2, the U.S. Air Force Academy satellite that the rocket was supposed to put into orbit.

FalconSat 2, a cube of thin metal and electronics that was about the size of a countertop TV, looked as if it had been kicked around the parking lot. Musk made a point of telling us not to take pictures of the mess. With SpaceX's cooperation, the U.S. military is still in the midst of an "anomaly investigation" to figure out exactly what went wrong and how to avoid a repeat.

Musk told us the investigation should be finished up within six weeks or so. Last month, he said that the root cause of March's fuel leak and resulting launch failure appeared to be "a pad processing error the day before the launch," but he declined to go further into the details today.

He did go into detail about SpaceX's future plans, however. The schedule calls for that second demonstration flight in September or October, funded by the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. If that goes well, yet another Falcon 1 launch would put the military's TacSat 1 telecommunications satellite into orbit (along with a secondary payload of cremated remains) in the December-January time frame.

The launch of a Malaysian satellite is penciled in for February-March 2007, then perhaps another TacSat launch in May or June of that year, he said.

"Falcon 1 may end up being the most launched vehicle in the world in a year," Musk said. Eventually, he said, "we may very well see upwards of 10 launches a year of the Falcon 1."

At one point, SpaceX had planned to offer a Falcon 5, with five engines in the first stage and one engine in the second stage. But Musk said "we're trying to decide whether it actually makes sense to fly the Falcon 5 or not." The alternative would be to go directly to the Falcon 9, which uses a 9+1 engine configuration.

The point of all this is to reduce the cost of access to orbit dramatically. The price tag for a Falcon 1 launch is $6.7 million, and Musk says the cost for a Falcon 9 would be $27 million. That could reduce the cost of putting paying passengers in orbit from the current $20 million a seat (on a Russian Soyuz rocket) to less than $10 million, he said — and provide a nicer overall experience as well.

"Instead of spending six months in training in Russia, you could spend six weeks in Santa Barbara at a spa," he quipped.

Looking even further out, Musk is hoping to develop an ultra-heavy-lift rocket that would be almost an order of magnitude more powerful than the Falcon 9. "That vehicle would be capable of getting 100 tons to orbit," he said. That's roughly equivalent to the power of the Apollo-era Saturn 5, or about four times the payload capacity of the space shuttle.

Some observers are already asking why on Earth Musk is contemplating a Saturn 5-class ultra-heavy-lifter, which he has nicknamed the BFR (he didn't spell out the acronym, although he noted that the rocket would be "frickin' big"). Maybe the motivation goes back to the part about extending life to other planets.

Would Musk himself want to go into space? He may have thought about it, but when he responded to that question today, he took the wider view once again. "This is not really about me going up," he said. "It would be very easy to buy a ticket from the Russians — a lot easier than starting a rocket company, and a lot cheaper."

• May 3, 2006 |

Green light for H Prize: The House Science Committee today green-lighted legislation that would create a series of multimillion-dollar prizes to promote hydrogen-based energy systems. The "H Prize" proposal, introduced by Rep. Bob Inglis, R-S.C., now goes to the House floor for consideration.

As expected, the legislation was fine-tuned to address concerns raised during a committee hearing last week. The federal contribution to the biggest prize has been capped at $10 million; however, private funds could still boost the total grand prize to $50 million or even as much as $100 million. The authorized spending for the prize program was reduced from $55 million to $11 million. And, according to the Science Committee, the bill was also amended to "clearly delineate the duties of the private entity that will be contracted to administer the prize program."

• May 3, 2006 |

Wonder and whimsy on the World Wide Web:

• Defense Tech: New detectors sniff terrorists' scents• The Guardian: Cloaking device isn't just sci-fi• Improbable Research: Foucault, footy and philosophy• The Onion: NASA plans to launch $700 million into space

• May 2, 2006 |

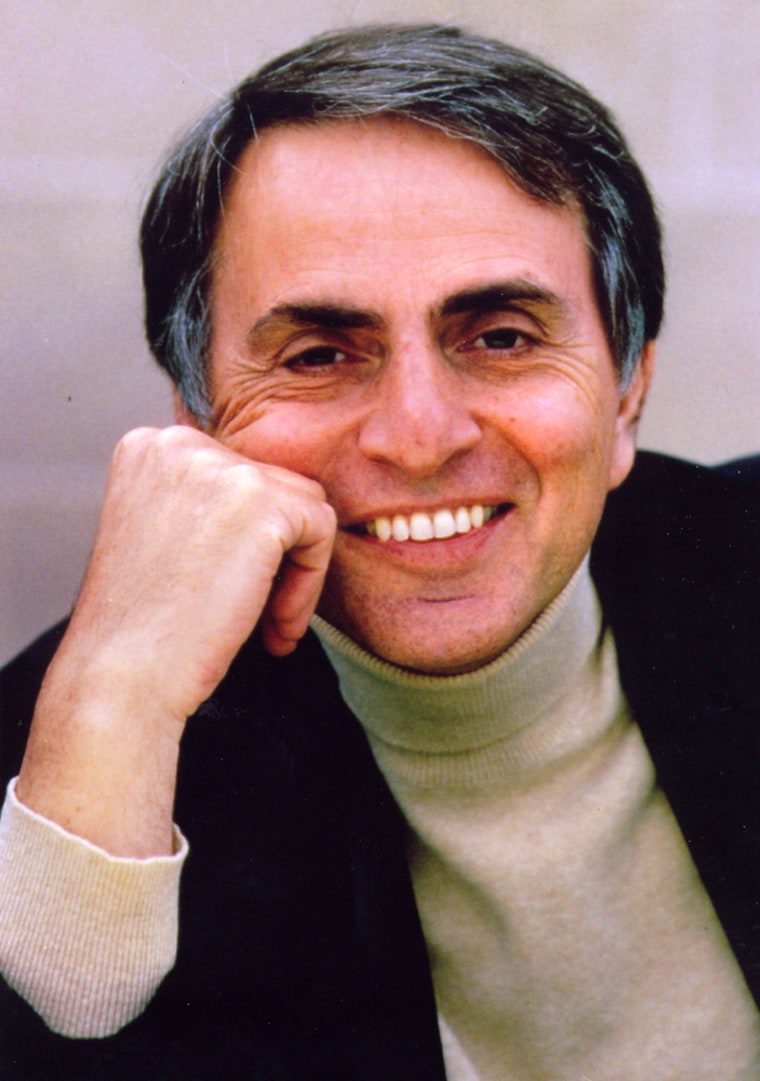

Carl Sagan’s spiritual quest: He was often asked whether he believed in God, and his stock answer was that it all depended on what your definition of "God" was.

He's been called an atheist, even though he's also quoted as saying that "by some definitions atheism is very stupid."

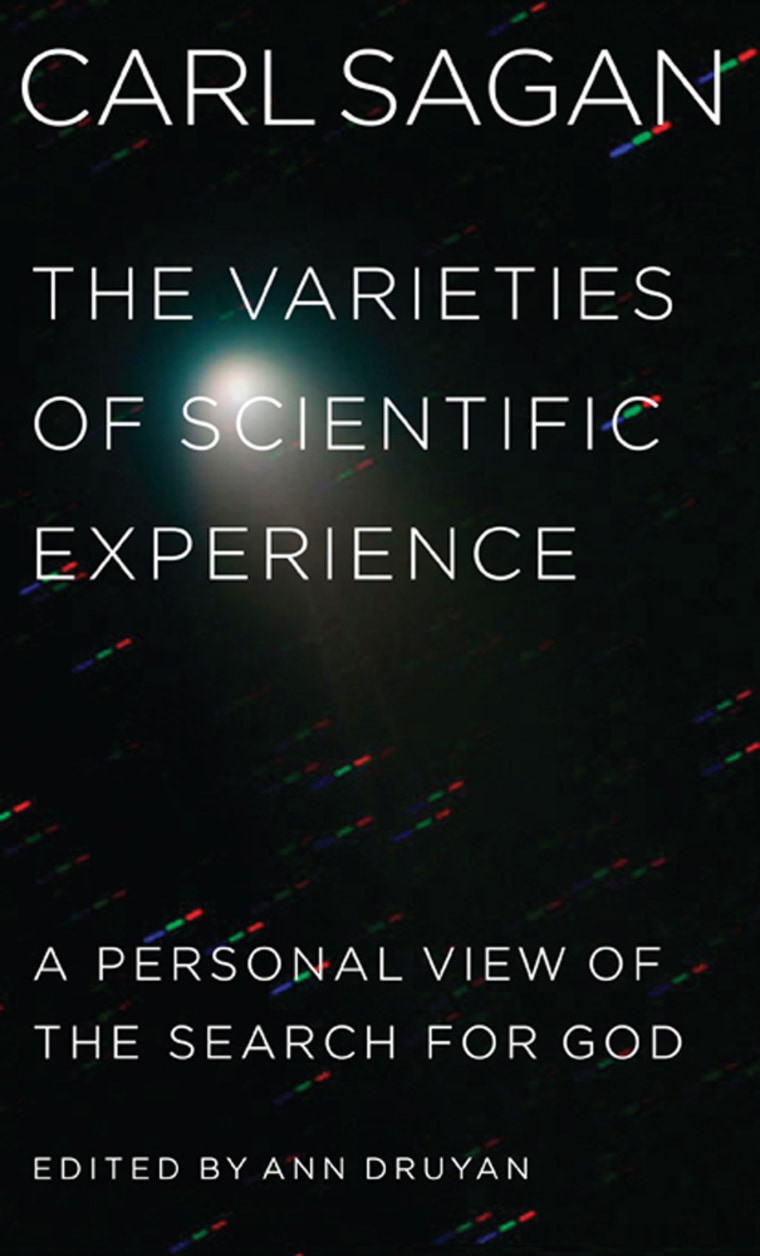

When it came to his spiritual perspective, the late astronomer Carl Sagan was always a bit hard to pin down, even though much of what he had to say about the cosmos was filled with spirituality. This year, however — a decade after his death from a rare bone-marrow disease — some of Sagan's deepest thoughts on the ultimate questions are being brought to light in a newly rediscovered collection of lectures titled "The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God."

The book, due for publication in November by The Penguin Press, is based on a series of talks Sagan gave at the University of Glasgow in 1985 as part of the Gifford Lectures on natural theology. After lying hidden for decades in Sagan's archives, the transcripts of the nine taped lectures were rediscovered just a few months ago, said Ann Druyan, the scientist's widow and longtime collaborator.

The title of the new book plays off "The Varieties of Religious Experience," a compilation of the Gifford Lectures given by American psychologist/philosopher William James a century ago, Druyan told me today.

"I wanted this book," Druyan said of the new volume, "because Carl put so much of his soul and heart and brain into giving lectures that were nearly perfect as spoken."

Druyan, who is now the chief executive officer of Cosmos Studios, edited the transcripts of the lectures, including the Q&A sessions that followed each talk. She also updated the text's scientific references with the aid of astrophysicist Steven Soter.

"Part of this experience gave me the happy fantasy that I was working with Carl again," she said, "because his voice was talking inside my head even more than it usually does."

So what did Sagan really think about God and religion? Druyan told me that's still the question she sees most frequently in the e-mail she gets via the CarlSagan.com Web site. She doesn't have a simple answer. If you had to put a label on Sagan's views, "agnostic" might come closest to the mark — but it's not agnosticism in the sense of an absence of knowledge, or a sense that the spiritual search is irrelevant.

"The little we do know is inspiring," Druyan said. "It's not true that we know nothing. We know something. It's tiny. But it's enough to base a kind of spiritual outlook on."

Druyan said Sagan's main theme was "the devoutness of the search itself, of being absolutely true in your searching to the methodology of science, to the error-correcting mechanism."

"In a way it makes someone who thinks that our spiritual understanding of the universe is complete seem that much less devout," she said. "His argument is not with God in this book. His argument is with those people who think that we know everything that we need to know about God. Rather than being dismissive or contemptuous of anybody, he takes the science he knew, everthing that he gathered in his life, and offers it as a way of explaining how he came to believe what he believed."

Druyan said two of the lectures serve as a "brilliant anticipation" of the claims for intelligent design — that is, the idea that some elements of nature are so complex that they had to have been designed by an intelligent agent (e.g., God). Back then, the concept was framed as creationism, or creation science.

"Every 20 years or so it rears its head once again, and scientists have to deal with it," Druyan said.

But it wasn't Sagan's style to belittle the defenders of the faith. "This is a deep Carl, it's a very loving Carl, it's a Carl who is not out to make other people look foolish," Druyan said. Rather, Sagan saw the varieties of scientific experience as stages in a quest on the scale of the spiritual quest.

"Whether he knew it or not — and I think he did ... he was talking about science as a kind of informed worship," Druyan said. "Scientists have been very squeamish about this, about really going into it in any depth, until recently. Scientists have been loath to really talk about the oneness and that soaring feeling that science can give us. It's been part of their truce with religion. You know, 'You don't burn us at the stake anymore, and we won't try to attract your clients away from the way that you look at creation.' There have been some really great scientists and writers who hit these notes in one way or another, but I think this is a tremendously fulsome, beautiful expression of that impulse."

Although Druyan herself has been recognized as "one of the world's outstanding atheists," it's clear that her own views are as complex as Sagan's were. She said reviewing her husband's observations on natural theology reinforced life lessons "which I had forgotten, or which I received in a new light."

"Most of all, it was just a confirmation of what a great soul Carl was," she said. "At times I would become really choked up by the complexity and the depth of him as a person. It was a very powerful experience. Carl's been gone nearly 10 years, and yet his presence is more palpable in his absence than most people are when they're vibrantly alive."

• May 2, 2006 |

Discoveries on the scientific Web:

• New Scientist: The latest blip on asteroid alert list

• USA Today: Royal tomb found hidden in Maya pyramid

• Scotsman.com: Tune into the Da Vinci coda (via Daily Grail)

• Popular Mechanics: How far can you drive on a bushel of corn?

• May 1, 2006 |

H Prize on the fast track: After a serious reality check, legislation creating a multimillion-dollar prize program to encourage hydrogen-based energy innovations is likely to come to the House floor sometime in the next few weeks, the bill's sponsor says.

U.S. Rep. Bob Inglis, R-S.C., told me today that he was heartened by last Thursday's hearing on his "H Prize" proposal — even though the top prize, initially pegged at $100 million, will almost certainly be scaled down. The plan, modeled on the $10 million X Prize for private spaceflight, would reward innovation in fuel systems that use hydrogen rather than petroleum.

Inglis sees the move toward hydrogen as particularly crucial in light of America's current energy dependence on "sources that are unstable, and sources that now have significant new customers" — that is, oil-hungry China and India.

"I hope that the awareness of our precariousness is spreading in the Congress, and with it a resolve to take action with impatience and insistence, similar to that shown in the Apollo moon shots and the Manhattan Project," he said.

During Thursday's House Science Committee hearing, X Prize founder Peter Diamandis and other witnesses said inducement prizes could give a powerful push to technological innovation — in combination, of course, with the more traditional approach to research.

"Prizes add a really important mix to allow breakthroughs, because peer-reviewed research is typically focused on small, incremental advances," Diamandis told me after the hearing. Taken together, the teams going after a technology prize may spend several times the amount of the actual purse — as was the case for the X Prize, where the winning team alone spent more than $20 million to win $10 million.

Inglis' plan set forth a spectrum of prizes, ranging from $1 million annual awards to a $100 million grand prize. The legislation called for just $10 million of that big-ticket item to come from the federal budget, with the other $90 million contributed by private sponsors. Nevertheless, Energy subcommittee chairwoman Judy Biggert, R-Ill., said the figure sounded too high. Wouldn't the payoff in a multibillion-dollar energy market be enough?

"I am in no way convinced that we need to spend $100 million on such a prize. … The prize of all prizes — the Nobel Prize — is only a $1.3 million award," she said.

Inglis indicated that he had taken such comments to heart, with the bill due to undergo markup in committee on Wednesday.

"I had hoped for a $100 million grand prize," he said today. "Now it looks like it may be $50 million," with $40 million in private money supplementing $10 million in public funds.

After consulting with experts, Inglis said he was "optimistic that we can actually find that $40 million."

Inglis is also sensitive to the observation that hydrogen is really a carrier of energy rather than a direct energy source. "When you're dealing with hydrogen, you've got to spend some energy," he conceded. "It is, however, an extremely useful energy carrier because it's so common and it's so clean."

In a way, even petroleum is a carrier of energy, he said — that is, energy that was deposited millions of years ago as carboniferous organic material, which ultimately traces back to solar energy. As that in-the-ground energy carrier becomes scarcer, America may have to turn gradually to hydrogen for the next phase of its energy economy, he said.

In the initial stages, producers may have to start out by converting carbon-based fuel sources — such as natural gas, ethanol or coal-based syngas — into hydrogen. But even that would be "an improvement over what we have now," with the potential of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by up to 60 percent, he said.

Inglis hoped that the initial wave of hydrogen-based energy technologies would give way to better systems, just as the music industry started out with records, then progressed to 8-track tapes, then cassettes, then CDs, then MP3 players. When it comes to promoting pioneering energy technologies, "we shouldn't pooh-pooh the 8-track," he said.

Meanwhile, the X Prize Foundation's Diamandis says prizes are becoming a "new hot subject" in government circles — not only for the energy sector, but also for NASA (which is heavily into its own Centennial Challenges program), the National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (which announced its third DARPA Grand Challenge competition just today).

"I wouldn't be surprised if prizes became a useful tool and a central strategy for all government agencies in the future," he told me.

• May 1, 2006 |

Your daily dose of science on the Web:

• Slate Meaning of Life: Are computers conscious?• Technology Review: Tiny electrodes for the brain

• Science News: Ultrasound's new focus• N.Y. Times (reg. req.): The greenest car? A dirty one

Looking for older items? Check the . Share your perspective on cosmic subjects with . If you link to this page, you can use or as the address. MSNBC is not responsible for the content of Internet links.