He was often asked whether he believed in God, and his stock answer was that it all depended on what your definition of "God" was.

He's been called an atheist, even though he's also quoted as saying that "by some definitions atheism is very stupid."

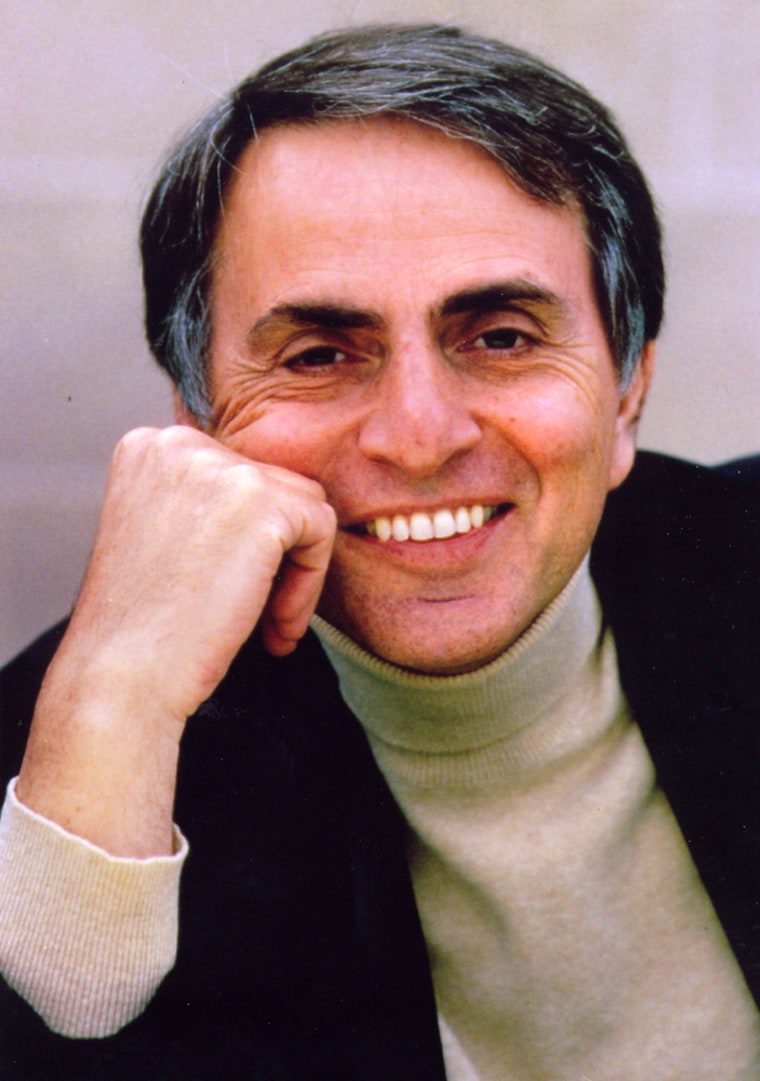

When it came to his spiritual perspective, the late astronomer Carl Sagan was always a bit hard to pin down, even though much of what he had to say about the cosmos was filled with spirituality. This year, however — a decade after his death from a rare bone-marrow disease — some of Sagan's deepest thoughts on the ultimate questions are being brought to light in a newly rediscovered collection of lectures titled "The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God."

The book, due for publication in November by The Penguin Press, is based on a series of talks Sagan gave at the University of Glasgow in 1985 as part of the Gifford Lectures on natural theology. After lying hidden for decades in Sagan's archives, the transcripts of the nine taped lectures were rediscovered just a few months ago, said Ann Druyan, the scientist's widow and longtime collaborator.

The title of the new book plays off "The Varieties of Religious Experience," a compilation of the Gifford Lectures given by American psychologist/philosopher William James a century ago, Druyan told me today.

"I wanted this book," Druyan said of the new volume, "because Carl put so much of his soul and heart and brain into giving lectures that were nearly perfect as spoken."

Druyan, who is now the chief executive officer of Cosmos Studios, edited the transcripts of the lectures, including the Q&A sessions that followed each talk. She also updated the text's scientific references with the aid of astrophysicist Steven Soter.

"Part of this experience gave me the happy fantasy that I was working with Carl again," she said, "because his voice was talking inside my head even more than it usually does."

So what did Sagan really think about God and religion? Druyan told me that's still the question she sees most frequently in the e-mail she gets via the CarlSagan.com Web site. She doesn't have a simple answer. If you had to put a label on Sagan's views, "agnostic" might come closest to the mark — but it's not agnosticism in the sense of an absence of knowledge, or a sense that the spiritual search is irrelevant.

"The little we do know is inspiring," Druyan said. "It's not true that we know nothing. We know something. It's tiny. But it's enough to base a kind of spiritual outlook on."

Druyan said Sagan's main theme was "the devoutness of the search itself, of being absolutely true in your searching to the methodology of science, to the error-correcting mechanism."

"In a way it makes someone who thinks that our spiritual understanding of the universe is complete seem that much less devout," she said. "His argument is not with God in this book. His argument is with those people who think that we know everything that we need to know about God. Rather than being dismissive or contemptuous of anybody, he takes the science he knew, everthing that he gathered in his life, and offers it as a way of explaining how he came to believe what he believed."

Druyan said two of the lectures serve as a "brilliant anticipation" of the claims for intelligent design — that is, the idea that some elements of nature are so complex that they had to have been designed by an intelligent agent (e.g., God). Back then, the concept was framed as creationism, or creation science.

"Every 20 years or so it rears its head once again, and scientists have to deal with it," Druyan said.

But it wasn't Sagan's style to belittle the defenders of the faith. "This is a deep Carl, it's a very loving Carl, it's a Carl who is not out to make other people look foolish," Druyan said. Rather, Sagan saw the varieties of scientific experience as stages in a quest on the scale of the spiritual quest.

"Whether he knew it or not — and I think he did ... he was talking about science as a kind of informed worship," Druyan said. "Scientists have been very squeamish about this, about really going into it in any depth, until recently. Scientists have been loath to really talk about the oneness and that soaring feeling that science can give us. It's been part of their truce with religion. You know, 'You don't burn us at the stake anymore, and we won't try to attract your clients away from the way that you look at creation.' There have been some really great scientists and writers who hit these notes in one way or another, but I think this is a tremendously fulsome, beautiful expression of that impulse."

Although Druyan herself has been recognized as "one of the world's outstanding atheists," it's clear that her own views are as complex as Sagan's were. She said reviewing her husband's observations on natural theology reinforced life lessons "which I had forgotten, or which I received in a new light."

"Most of all, it was just a confirmation of what a great soul Carl was," she said. "At times I would become really choked up by the complexity and the depth of him as a person. It was a very powerful experience. Carl's been gone nearly 10 years, and yet his presence is more palpable in his absence than most people are when they're vibrantly alive."

This report originally appeared as a Cosmic Log posting on May 2, 2006.