We’ve all seen the popular cartoon of evolution’s march from an ancient sea, beginning with a single floating cell that morphs into increasingly complicated creatures, on the way to the punch line of Weekend Man slumped in his armchair.

It’s just a joke, but the idea that life starts simple and gets more complex over time persists even in scientific circles. Yet one of the biggest events in evolutionary history — the origin of the cells that make up every tissue in our bodies — may be a case of life getting less complicated, according to recent research.

These types of cells are called eukaryotes, and they're found in organisms from fungi to humans. They look like the souped-up versions of simpler cells such as bacteria and their distant cousins called archaea. Many researchers think eukaryotes are the descendants of either bacteria or archaea, or some combination of the two. But genetic and protein evidence do not support this view, researchers report in Friday’s issue of the journal Science, published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

Instead, the data suggest that eukaryote cells with all their bells and whistles are probably as ancient as bacteria and archaea, and may have even appeared first, with bacteria and archaea appearing later as stripped-down versions of eukaryotes, according to David Penny, a molecular biologist at Massey University in New Zealand.

Penny, who worked on the research with Chuck Kurland of Sweden's Lund University and Massey University's L.J. Collins, acknowledged that the results might come as a surprise.

“We do think there is a tendency to look at evolution as progressive,” he said. “We prefer to think of evolution as backwards, sideways, and occasionally forward.”

Failure of fusion

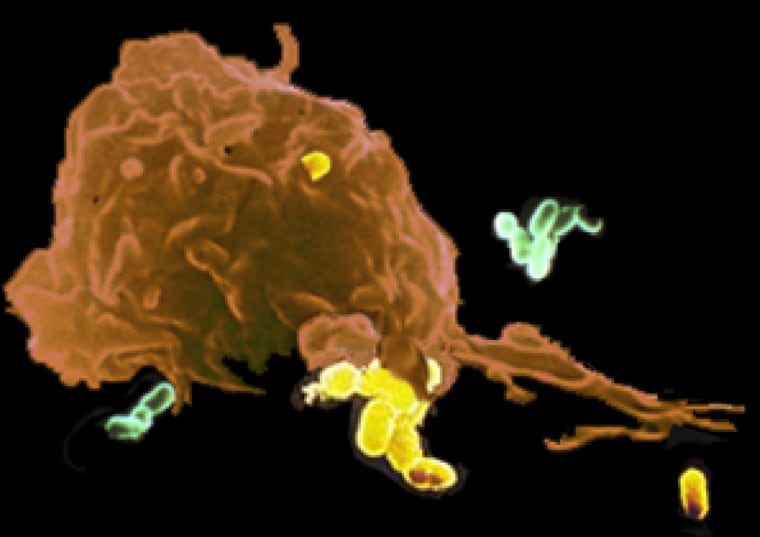

The landscape inside a bacteria cell is pretty sparse, consisting mostly of free-floating genetic material. By contrast, the inside of a eukaryote cell is a bustling metropolis, crowded with a variety of protein factories, control rooms, transportation routes and a central bundle called the nucleus that contains the cell’s genetic information. Eukaryote cells also have a unique set of genes and proteins.

If the first eukaryotes were a fusion of ancient bacteria and archaea, as some scientists suspect, there should be clues in the eukaryote genome and proteome that point back toward these putative ancestors. Penny and colleagues say those clues simply aren’t there. Instead, the say the fusion theory is “surprisingly uninformative” when it comes explaining the special genetic and cellular features of eukaryotes. Most of the proteins that eukaryotes and bacteria share, for instance, are only distantly related and probably came from the common ancestor of both bacteria and eukaryotes.

Some researchers think the fusion of simple bacterial cells may have created the compartments and tiny organlike structures that fill the insides of eukaryote cells. But Penny and colleagues say another phenomenon called “molecular crowding” could also explain the unique architecture of eukaryotes. When cells become crammed with proteins in a concentration so thick “it’s almost like jelly,” Penny says, it becomes hard for the proteins to move and work together. To avoid this problem, “working groups” of proteins sort themselves into separate compartments.

“Because protein diffusion is so restricted under such high concentrations, it is really essential, especially in large cells, to have proteins together that function together,” Penny says.

Fully loaded, or priced to move?

If eukaryotes didn’t originate with bacteria and archaea, is it possible that the simple cell organisms are just stripped-down versions of eukaryotes? Although the idea seems contrary to our cherished notion that evolution makes organisms more complex, Penny and colleagues say it’s possible.

Think of it as the new car dilemma: Do you spring for the fully loaded model, complete with sunroof, satellite radio and side airbags? Or do you opt for the basic model, with less features but a lower cost? Bacteria and archaea may be the “priced to move” models of eukaryotes, cells that opted out of the costly cellular gadgetry and large genomes of eukaryotes. Without these expensive extras, early bacteria could have turned their energies toward growing and reproducing faster using fewer resources — making it easier to advance into new ecological niches, Penny and colleagues say.

Bacterial ancestors may have been forced into simpler lives by the appearance of the first cell to feed on other cells, an ancestral predatory eukaryote that Penny and colleagues have dubbed “Fred the Raptor.” Fred’s debut “would have had a major ecological impact on the evolution of gentler descendants of the Common Ancestor,” the Science researchers suggest.

If early bacteria did take the road toward greater simplicity, they would be in good company. Scientists have identified several cases of genome reduction in organisms as diverse as the malaria parasite and bakers’ yeast, Penny says.

The numerous examples “illustrate the Darwinian view of evolution as a reversible process in the sense that ‘eyes can be acquired and eyes can be lost.’ Genome evolution is a two-way street,” Kurland says.