WASHINGTON – In Washington the other day, I got a chance to tell Al Gore something I’d meant to say for a long time, which was that I thought his real strength, his real contribution, was as an observer — writer, explainer, outsider — and not as a politician.

The new movie about him was evidence of that, I said. He gave me a blank, dismissive look, and an “umm” for a verbal response.

I’ve known and covered Gore for decades, so maybe his reaction was inspired by Groucho Marx, who always said that he would never join a club that would have him as a member. But I think the brusque reply carried a different message: don’t assume that I’m ready to be put out to that pasture just yet.

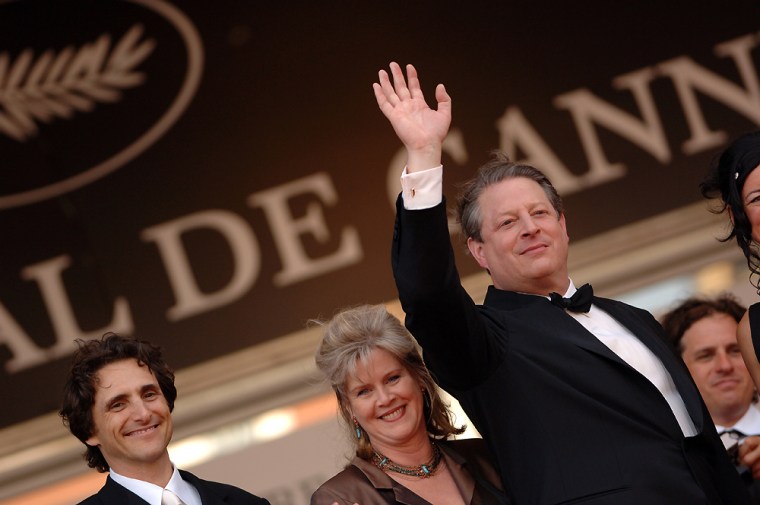

Gore has a certain aura of nobility about him these days — a mixture of rue, acceptance and lofty goals that makes him almost, well, endearing. As I talked to him at the East Coast premiere of the documentary film about him (“An Inconvenient Truth’), I wondered whether his new-found sense of peace and purpose meant that he had given up the idea of ever running for president again — or whether that is precisely what, in an indirect, Zen-like way, he’s doing. My answer to my question: he’s available if fate decides to befriend him.

The premiere, at the headquarters of the National Geographic, had the aura of a Washington homecoming. But it was a non-political political reemergence after an (understandably) long, post-2000 convalescence. It didn’t feel like a fundraiser or a campaign launch — just a chance to see an unusual film, starring a fellow that everyone in the auditorium knew, and many admired.

It seems hard to dispute that Al Gore finally has built the life he wanted — and that it is outside of electoral politics. Davis Guggenheim, who directed the documentary, focuses on everything but. The core of the film is Gore’s famously apocalyptic global-warming slide show. But Guggenheim weaves around it the story of the former vice president’s roots and rising, starting with the summers he spent on his parents’ (now his) cattle farm in Middle Tennessee.

Gore is depicted as a guy who learned to love the land; who was exposed to the pioneering work of an environmentalist at Harvard; who, seeing his older sister die from smoking cigarettes, came to despise the misuse of science in the name of commerce. Now he’s found his life’s calling in his missionary work: an itinerant preacher dragging a black wheelie and an Apple laptop through airports as he summons mankind to repel the Forces of Doom.

The movie works better — is far more inspiring — if you don’t think that Gore is running for president. And, at the reception afterwards, he didn’t seem to be. He has lost a bit of his fastidiousness; all those globe-spanning trips through airports have left him on the portly side for the first time in his life. He was clutching a glass of red wine, not the early-evening drink of choice for a man prepping for a campaign marathon. Rather than work the crowd, the crowd worked him, and in the brief moments when there was a lull — when no one was pressing in on him — he was content to stand alone amid the babble.

If he is happy to be a selfless oracle, perhaps that is partly because he’s become a very wealthy one. I’m told that he has a ton of Google stock — he got in early — and that his investment firm is doing well, and that its work dovetails very nicely (logistically and financially) with his more visible environmental evangelism. He’s always been a devoted family man; now he’s a doting grandpa.

So why would he even fleetingly consider politics again?

For one – to paraphrase a slogan once applied to the late Barry Goldwater — in his heart, Gore knows he’s right. He’s been ahead of more curves than a NASCAR driver: the concerns about global warming, the implications of the rise of the internet, the need to be wary of deadly friction along the faultline between Islam and the West, his early and deep opposition to the launching a war in Iraq. It’s an impressive record.

“The reason people don’t like Gore is that he has been right so damn many times,” James Carville told me with an appreciate laugh.

And Guggenheim has created a portrait of Gore that Gore himself might well find appealing — a mirror on the wall that the former vice president can’t help but peer into.

There is interesting historical resonance here. The director is the son of the Charles Guggenheim, a pioneer documentarian who won an Academy Award for his 1968 portrayal of the life and death of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. A full generation later, Guggenheim’s son makes a film unlike any to come out of Hollywood since: one that paints a politician in a heroic light.

In the book that accompanies the film, Gore doesn’t state in so many words that he would never run for president again. He hasn’t really said so elsewhere, either.

But here’s another inconvenient truth, this one political. In the film, Gore is appealing precisely BECAUSE he seems to have no other goal than to tell us the facts.

He’s trapped in his own greenhouse.