Scientists have found something about the North Pole that could send a shiver down Santa’s spine: It used to be downright balmy.

In fact, 55 million years ago the Arctic was once a lot like Miami, with warm average temperatures, alligator ancestors and palm trees, scientists say.

That conclusion, based on first-of-their-kind core samples extracted from more than 1,000 feet (300 meters) below the Arctic Ocean floor, is contained in three studies published in Thursday’s issue of the journal Nature. Scientists say the findings are both a glimpse backward at a region heated by naturally produced greenhouse gases run amok and a sneak peek at what human-caused global warming could do someday.

Scientists believe a simple fern may have been responsible for cooling things back down, by sucking up massive amounts of the carbon dioxide responsible for the warming. But this natural solution to global warming wasn’t exactly quick: It took about a million years.

Earth went through an extended period of natural global warming, capped off by a supercharged spike of carbon dioxide that accelerated the greenhouse effect even more about 55 million years ago. Scientists already knew this “thermal event” happened, but figured that while the rest of the world got really hot, the polar regions were still comfortably cooler, maybe about 52 degrees Fahrenheit (11 degrees Celsius) on average.

But the new research from the multinational Arctic Coring Expedition found the polar average was closer to 74 degrees F (23 degrees C).

‘Big surprise’

“It’s the first time we’ve looked at the Arctic, and man, it was a big surprise to us,” said study co-author Kathryn Moran, an oceanographer at the University of Rhode Island. “It’s a new look to how the earth can respond to these peaks in carbon dioxide.”

The 74-degree temperature — based on core samples, which act as a climatic time capsule — was probably the year-round average, but because the data is so limited, it could also be simply the summertime average, researchers said.

“Imagine a world where there are dense sequoia trees and cypress trees like in Florida that ring the Arctic Ocean,” said Yale geology professor Mark Pagani, a study co-author. He said it was probably a tropical paradise, “but the mosquitoes were probably the size of your head.”

Cause is still a mystery

Researchers are not sure what caused the sudden boost of carbon dioxide that set the greenhouse effect on broil. Possible culprits could be huge releases of methane from the ocean, gigantic continent-sized burning of trees, or lots of volcanic eruptions.

What’s troubling is that this suggests the current projections, which say Earth will grow warmer by several degrees over the next century, may be on the low end, said the study’s lead author, Appy Sluijs of the Institute of Environmental Biology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

Also, the findings are proof that too much carbon dioxide — more than four times current levels — can cause global warming, said another co-author, Henk Brinkhuis of Utrecht University.

Purdue University atmospheric sciences professor Gabriel Bowen, who was not part of the team, praised the work and said it showed that are “tipping points” in the Earth’s climatic system “that can throw us to these conditions.”

Ferns to the rescue?

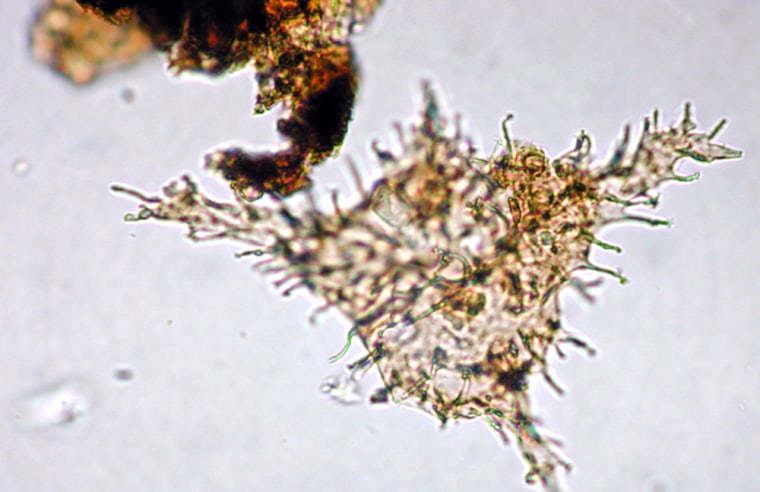

With all that heat and big freshwater lakes forming in the Arctic, a fern called Azolla started growing and growing. Azolla, the fastest-growing plant on Earth, eventually started sucking up carbon dioxide and helped cool the Arctic, Brinkhuis theorized.

Bowen said he has a hard time accepting that part of the research, but Brinkhuis said the studies show tons upon tons of thick mats of Azolla covered the Arctic and moved south.