NASA’s top safety official objected to the agency’s decision to press ahead with the launch of Discovery next month without fixing a potentially catastrophic foam-shedding problem, but said he won’t appeal — and won’t resign in protest — because he does not believe the shuttle astronauts’ lives are in danger.

“It’s a done deal,” NASA chief safety officer Bryan O’Connor said in a Monday night interview with The Associated Press.

O’Connor, a former shuttle commander, said he was uncomfortable with going ahead with the launch on July 1 but accepted the decision because NASA has plans in place to have the crew take refuge in the international space station and wait for a rescue mission if foam punches too big a hole in the shuttle’s heat protection system.

He and shuttle program manager Wayne Hale, who have spent decades in the program, said they could not recall a previous instance in which a launch proceeded over the objections of the safety office.

Ten years ago, O’Connor quit his job as chief of the space shuttle program over a reorganization that he said would threaten crew safety. But he said this disagreement was not nearly as worrisome: “I wasn’t anywhere close to that.”

Decided against last-ditch appeal

O’Connor, who along with NASA Chief Engineer Christopher Scolese voted against a launch during the flight-readiness meeting held over the weekend at Kennedy Space Center, said he and Scolese could have made one last-ditch private appeal to NASA Administrator Michael Griffin, who made the ultimate decision. But they did not.

O’Connor said he told Griffin he would have appealed had he thought the crew’s lives were in danger.

“It’s a real close call,” O’Connor said, adding that his own office was split, with some safety officials thinking that it wasn’t as big a problem as he thought.

In 2003, a chunk of insulating foam broke off from Columbia’s big external fuel tank at liftoff and punched a hole in the shuttle’s heat-protecting skin, leading to the breakup of the spacecraft during its return to Earth and the deaths of all seven astronauts.

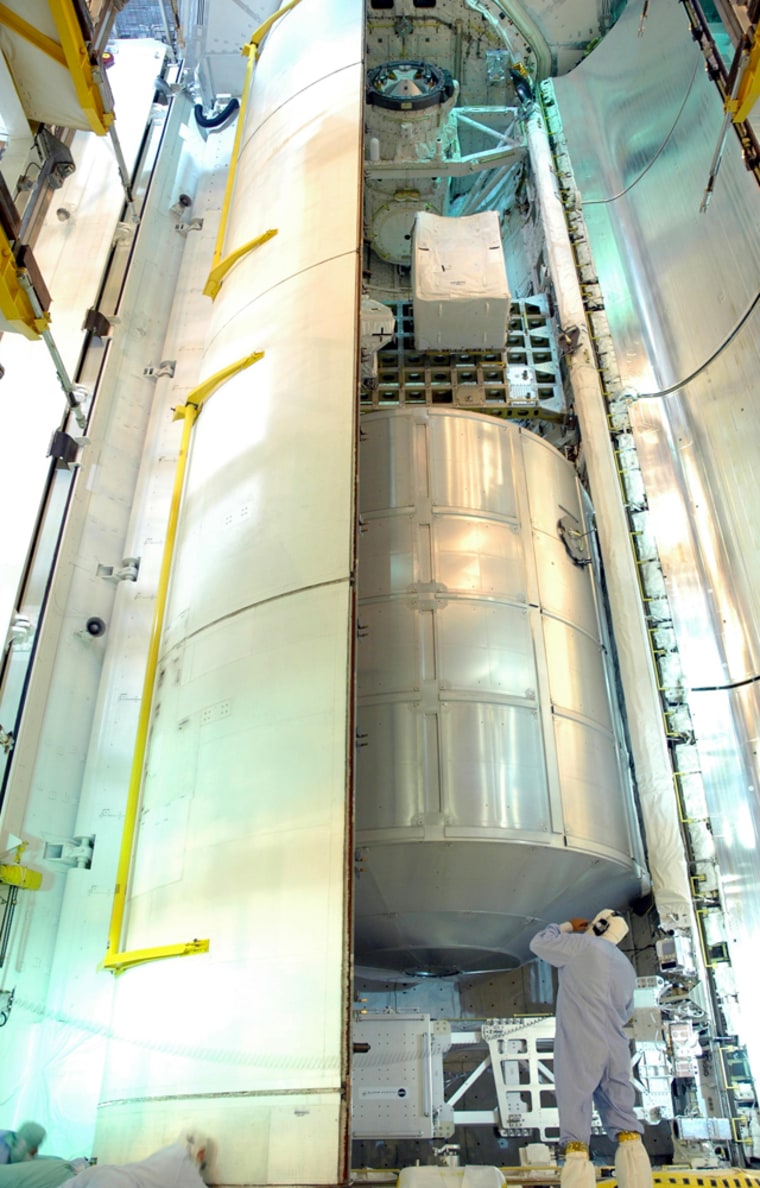

Despite extensive modifications to the fuel tank over the more than two years that followed, large pieces of foam broke off again when Discovery lifted off last summer on the first flight since the disaster.

More modifications followed, but NASA decided to move ahead without removing foam from some particularly troublesome spots called the ice/frost ramps.

Risk added to flight — but how much?

That decision adds risk to the flight, O’Connor said. But he and Hale said they couldn’t estimate how much added risk.

“It should have not gotten to the point where we’d say this is something we could fly with,” O’Connor said. “We wish we understood the physics a little better.”

On Tuesday, NASA released a copy of the Certificate of Flight Readiness for Discovery. On the document, Scolese and O’Connor crossed out sections where it says they concur with the decision to launch. They wrote out their objections by hand.

Scolese scrawled: “I remain no go based on potential loss of vehicle, however for this mission I have no intention to appeal the decision based upon ISS capability” — a reference to the space station’s availability as a safe harbor.

O’Connor worked with the independent board that investigated the 1986 Challenger explosion and became the agency’s safety chief eight months before Columbia was lost in February 2003.

O’Connor said he worried that NASA’s tight schedule — trying to complete construction of the space station and retire the shuttles in 2010 — could be interfering with safety.

“There’s definitely schedule pressure. You can’t make it go away,” O’Connor said.

But on Tuesday, in a series of satellite television interviews, Hale disputed that. “There is no consideration of schedule pressure in the safety arena,” he said.

Statement written by others

NASA’s public affairs office — which earlier this year was accused by top global warming scientist of trying to muzzle his media interviews — said on Monday that O’Connor and Scolese would not talk to the media about their objections.

NASA chief spokesman Dean Acosta said it was a decision by the two men. He released a two-paragraph statement and said O’Connor and Scolese “composed it together.”

O’Connor, who readily agreed to a 20-minute phone interview, said the statement was actually written by the public affairs office and approved by the two officials.