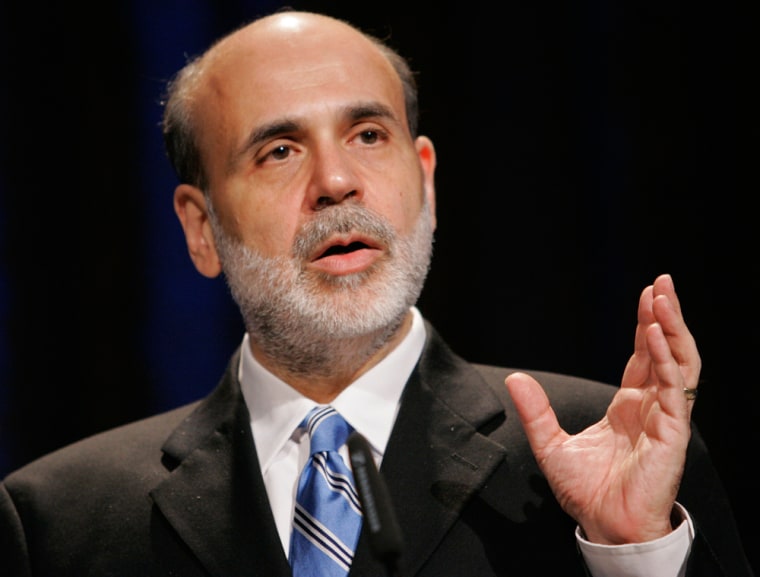

The Federal Reserve is as stodgy an institution as you'll ever find. Chairman Ben Bernanke doesn't pull rabbits out of top hats or break into song when he testifies before Congress. Nevertheless, some observers of the U.S. central bank are wondering whether the Fed might have a big surprise in store for Thursday, June 29, when it announces the deliberations of its rate-setting committee.

The unlikely-but-possible surprise: A double dose of rate-hiking medicine. In other words, the Fed might raise the federal funds rate by half a percentage point instead of the quarter percentage point that the market is widely expecting. If it doubled the dose, interest rates would probably leap across the credit spectrum, from yields on certificates of deposit to rates on 30-year mortgage loans. But, later, rates on such long-term debt as mortgages might actually fall if investors concluded that the half-point increase was probably the Fed's last hurrah.

Why would the Fed suddenly hike the rate a half-point, to 5.5%, when it has methodically notched an additional one-quarter point at each of the past 16 meetings going back to June, 2004? The double dose would show that the central bank is serious about stopping inflation, says David Rosenberg, chief North American economist of Merrill Lynch -- who hastens to add that he isn't actually predicting a half-point rise on June 29. And by proving its anti-inflation credentials once and for all, it might actually allow the Fed to stop raising from then on.

Right now, the Fed's dilemma is that rate hikes that come out in dribs and drabs weaken the economy without convincing the inflation hawks in the markets that the Fed has matters in hand. The stock market might stage a huge rally in the next few months if investors see a half-point increase and conclude that the Fed's rate-raising campaign is finally over, Rosenberg wrote to clients on June 26.

You can tell by prices in the money market that at least some traders expect a bigger hike, beyond the widely expected rise to 5.25%. The evidence: The one-month futures contract for federal funds was trading on June 26 at 5.3%. Locking in a 5.3% rate on fed funds for the coming month would be a mistake unless you see at least some chance that the rate will actually go up to 5.5% on June 29. By one estimate, the market sees a 12% chance of a half-point rise.

Global concerns

Another hint of a double dose comes from the Fed's Open Market Committee itself. According to the minutes of its May 10 meeting, the rate-setters "discussed policy approaches ranging from leaving the stance of policy unchanged at this meeting to increasing the federal funds rate 50 basis points." (Fifty basis points equals half a percentage point.) The very fact that a half-percentage-point rise was mentioned as a possibility in the minutes is significant, in Rosenberg's view. "They didn't have to throw in that line," he wrote on June 26.

To be sure, a half-point rise is just a glimmer in the eye. "We think it's highly unlikely," says Standard & Poor's economist Beth Ann Bovino. Also, it's impossible to say how markets would react. Ashraf Laidi, chief currency analyst of MG Financial Group, worries that a half-point rise would hurt the global stock markets, which are already unsettled by tightening by the world's central banks.

That kind of market turmoil could then cause the Bank of Japan to delay an overdue increase in its own short-term rates, Laidi wrote on June 26. Still, Laidi acknowledges that a half-point rise isn't out of the question. "The justification for such aggressive policy action," he wrote, "is in place."

"Like snowflakes"

New research by Standard & Poor's chief investment strategist Sam Stovall shows that the stock market doesn't reliably rise once the Fed stops raising rates. Going back to the early 1970s, there was an average of seven months between the time the Fed stopped raising and the time it started cutting because the economy was slowing down too much. During that period, the S&P 500-stock index rose an average of 3%. The performance of the index during these plateaus ranged from a low of negative 24% in 1971-74 to a high of positive 34% in 1997.

On the plus side, Stovall is optimistic about what might happen to stocks this time if the Fed goes with a double dose on June 29. He thinks investors would be exhilarated because they would conclude the worst is over. "It's like snowflakes," says Stovall. "The biggest ones fall at the end of the storm."