• July 7, 2006 |

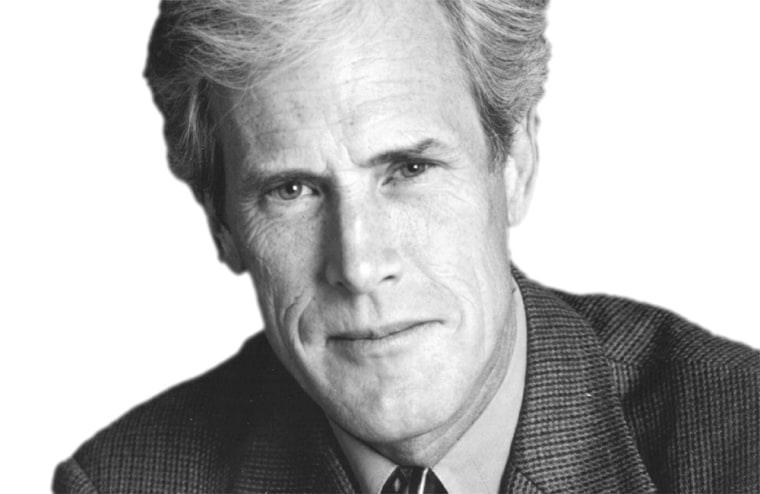

The Miraculous Life of Jonathan Swain (Keith Morrison, Dateline correspondent)

So here I was, fighting a miserable cold, trying to avoid touching people or sneezing on them, sitting in a prison in Dublin, California, and listening to a heartbroken woman talk about the love of her life — her son. And I was thinking once again that the truth of what happens to people is just too strange, too improbable, to ever make up. This woman was in prison on a drug charge, having become an addict in the midst of the pressure of trying to raise a son who had been infected with AIDS by a blood transfusion administered within a few days of his birth. She was telling me how she had been told to prepare for his death (which surely would come very soon), and how her church asked her not to go there anymore, and how she prepared a death notice in advance but when she went to an undertaker he told her he would refuse to accept the baby boy's body at his establishment.

Suddenly my cold didn't seem like such a big deal.

AIDS was the night terror of the 80s; nobody survived AIDS. And if a baby could catch it, couldn't anyone? Would saliva spread AIDS, or tears, or touch? They were real questions. And neither that young mother nor the surrounding community had answers. And so now we looked back from that prison interview on a world that pushed away the people and the illness that frightened them.

But, here's the amazing thing: the boy did not die. At least, not right away. Birthday after birthday, while she fought and lost her war with cocaine, her son somehow survived and grew, though all the while he and those around him understood that death could come to call any time. And now here she was in prison, coping with the guilt of a mother who abandoned the son who so needed her.

But what happened to him?

There is a town in Utah, 3 hours or so by car across scrub desert from Salt Lake, called Vernal. It is, by all appearances, a devoutly Mormon town, hardly the sort of place you'd expect a young man with a sentence of death-by-AIDS to come calling. But here was where he came, the scene of the rest of the improbable story, with a result no one predicted, and which that mother back in prison might never have believed possible.

The young man's name is John Swain. Watch what happened to him. See if it doesn't revise your ideas of what is possible in life.

A mother fights the odds to keep her ill son alive and healthy, becoming his biggest hero, then, years later she reveals a secret that shatters his world. Keith Morrison reports in this epic family drama about love, betrayal and survival. "The Miraculous Life of Jonathan Swain" airs Friday, July 7, 8 p.m.

• |

Are prospective parents who want to adopt easy targets? (Victoria Corderi, Dateline correspondent)

On certain stories, my faith in humanity gets tested. Because of the unique nature of my job, I have witnessed people at their best and at their worst, the caring and the callous. I saw both sides during the course of the compelling adoption story we are airing Friday night.

I met people from different parts of the country who had shared the same goal: to give a loving home to a baby who needed one. None of them arrived easily at the decision to adopt. It was only after years of trying to conceive, enduring miscarriages and costly fertility treatments that they'd finally reached a place of acceptance. And once they made the decision, they became hopeful, even enthusiastic. They learned that the Internet makes finding a birth mother potentially easier and more affordable. They were ready. They were willing. They were, in short, sitting ducks.

All of them knew to expect disappointments. They might spend time and money on a prospective birth mother, get emotionally invested, and then learn at the last minute that she changed her mind. But no one we met could imagine what they believe happened to them: that their situations would be exploited, that they would be targeted by someone who knew just what she was doing, just how to string them along, just how to play people who are desperate for a child.

How could it be done? We learned firsthand.

The Dateline report on the 'Web of Deceit' airs July 9, Sunday.

• July 6, 2006 |

How do you know when a scam is a scam? (Allison Orr, Dateline Producer)

When we set out to investigate private adoption scams, we knew we didn't want to do a typical story that simply re-told events that had happened in the past. Our goal was much more elaborate: to capture events in progress and follow them as they unfolded. All on camera, of course.

My first task was to figure out—could it be done? After-all, how common was the "birth-mother" scheme we were interested in? How many pregnant women (or women pretending to be pregnant) would falsely promise to give a child up for adoption in exchange for getting their rent and expenses paid? Surely, there seemed like an easier way to make a dishonest buck?

It didn't take long to conclude that this sort of con was a small but very real phenomenon. There are no statistics to rely on, but I very quickly found dozens of families, adoption attorneys and adoption agencies eager to share their own horror stories, and willing to help us find a case to profile for Dateline.

Now came the second and much bigger challenge-- deciding how and when to investigate an adoption in real time. After all, this wasn't like investigating a shady retailer, or a bogus government program. At the center of this story was an innocent human life. We couldn't do anything to disrupt what might otherwise be successful adoption. And our investigation was complicated by this key fact: in any private adoption it is perfectly legal for a pregnant woman to change her mind even after she's taken money from an adoptive family. If a woman offered a child and then reneged, how would we know it wasn't just a case of cold feet?

In January, I got a call about the Coleman's case through a series of contacts I'd made with various adoption professionals. The Colemans, a hopeful adoptive family from Tennessee, had been working with a pregnant woman named Christy for almost 2 months. They'd sent her money, met her in person and talked with her on the phone every day. Then Christy suddenly disappeared. Had she taken them for a ride, or simply changed her mind? Lori Coleman had done some investigating on her own and had good reason to believe that Christy had done this before. It sounded fishy.

As we began to investigate, one thing was clear-- "Christy" was not who she said she was. Her name, social security number, address and other personal details she'd provided to the Coleman's could not be verified. She was apparently lying about her identity, but was she lying about wanting to give her child to the Colemans?

Within days, "Christy" was back in touch with the Colemans and was again promising them her baby. They agreed to meet in person. A team of Dateliners— with hidden camera equipment—flew to Nashville to be there. From a Nashville hotel room, I worked the phones and the Internet--- calling contacts, reading adoption message boards, visiting adoption chatrooms: Had anyone heard of the woman who called herself Christy? Did they have documents? Photos? Could they send them now, tonight?

By the morning of our meeting with "Christy," I had talked to about a half dozen families or adoption agencies who believed they'd previously been conned by the person we were about to meet. Two families had even e-mailed photos of her. But the most compelling bit of evidence that "Christy" was not being honest about her adoption plans was something I witnessed with my own eyes.

The night before our meeting, "Christy" called Lori Coleman and asked for money to buy food. Lori left her a gift certificate the local Walmart, while another producer and I waited at the store for "Christy" to show up. Soon, we were following "Christy" around Walmart watching her shop. She bypassed the grocery section and went right for the baby department. I stood just a few feet from "Christy" as she casually fingered a rack of newborn outfits. I listened to her talk non-chalantly to her friend about needing baby bottles. And I watched her fill her cart with diapers. My gut said this is not what a woman does when she's about to give a child up for adoption. The scene reminded me of myself during those last weeks of pregnancy: browsing baby stores in anticipation, stocking up, as if shopping alone could ready oneself for the shock of becoming a mother.

As I watched "Christy" shop, I was becoming convinced — this woman was not planning to give her baby to the Colemans.