It was Camp Heartland’s first summer, and I was tense. “Would the kids get along with each other?” I asked myself. “Would they be in any danger?” What if someone gets ill?”

No more than 10 minutes after the campers arrived, I got an urgent call on my walkie-talkie. “There’s a kid in the infirmary already.” I hurried over to “Club Meds,” as we came to call it, lying on a cot was this 10-year-old boy with big blood-shot eyes. It was clear that he was very sick.

“Hi, I’m Noodle,” I said to him, using my camp nickname. “Welcome to Camp Heartland.” “I’m Ryan,” said the boy, managing a smile. “I want to take a nap for a little while.” And he drifted off to sleep...

Ryan was born on August 10, 1982, the first and only child of Mike and Debbie Chedester. The Chedesters lived in Whiteville, Louisiana, a community of about 200 people. Like many parents, Mike and Debbie didn’t care if their child was a boy or a girl. They just wanted a healthy child.

Unfortunately, things didn’t turn out that way.

After a difficult delivery, the doctor had dreadful news for Debbie and Mike. “Your child has severe internal bleeding. We don’t know what it is or how to stop it. His chances of survival are very slim.” Preparing for the worst, the Chedesters called their priest and asked him to baptize the baby. And they asked him to perform the Last Rites.

But this miracle baby wanted to live. Somehow, he survived Day One, and then Day two, and Day Three and Day Four. The bleeding was controlled, and after six weeks, Ryan was released from the hospital.

Around the sixth month of his life, Ryan’s parents noticed that he was bruising very easily. He had trouble learning to sit up, and his joints began swelling. The doctors diagnosed Ryan with hemophilia, a genetic blood-clotting disorder that can be exceptionally painful. Like all hemophiliacs, Ryan would be prone to severe swelling and bleeding around the joints.

As he grew into a toddler, at the insistence of his physician, Ryan’s parents began giving him a blood product, Factor VIII – made partly from donated bloom plasma. In some ways it was a life-saving product. His mother could give him Factor VIII through an infusion, and his blood would clot at a normal level if he were injured.

But there was a problem with the medication, an awful problem. Before 1982, neither the drug manufacturers nor the government knew that some of the blood used to make Factor VIII had been contaminated with HIV. And when they finally did find out, they delayed in announcing the danger until 1985. Unbeknownst to hemophiliac patients, some of their treatments were tainted with HIV.

Ryan was told by his mother that he had HIV when he was 9. It was an enormously difficult thing for Debbie to do — to sit down and essentially deliver a death sentence to her child. But at that time, there was very little hope for people with AIDS.

Ryan’s family decided to keep the news a secret. They were worried about a potentially negative reaction by his teachers and classmates and neighbors. They remembered another Ryan – Ryan White, the boy from Kokomo, Indiana, who had been shunned by friends and banned from public school. So they kept the news to themselves. Only Ryan’s immediate family and grandparents knew he was HIV positive.

In 1993, as summer approached, Ryan signed up for Camp Heartland. He was frightfully ill at the time with pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, a common illness for people with AIDS and a frequent cause of death. Breathing was nearly impossible for Ryan.

Again, Ryan prevailed. He survived the pneumonia. But his immune system suffered terribly. His T4-cells – an indicator of the state of immune system – fell to a dangerously low level. Yet he had made up his mind. “I want to go to camp,” he told his parents. “I want to have some fun for awhile…”

Ryan awoke from his nap after two or three hours. He was restless. "I need to get out of bed and do something," he said. "Thats why I came here, to have fun."

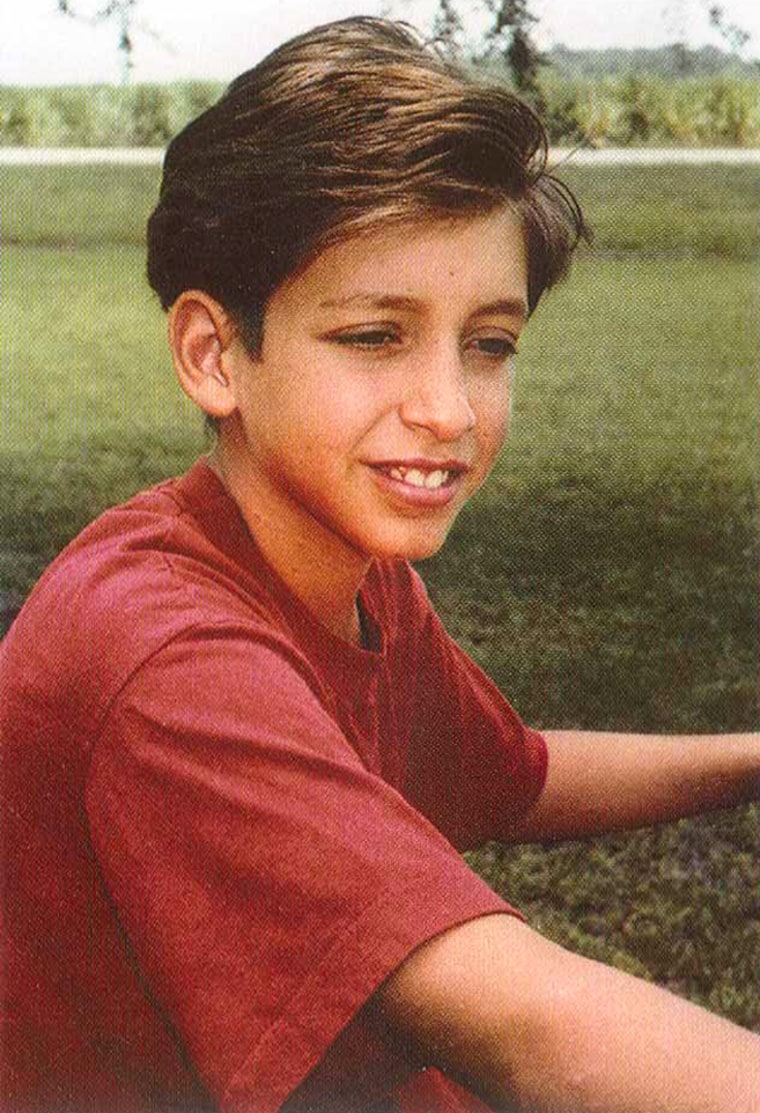

For the rest of that day, Ryan played football, mastered the climbing wall, and went canoeing. The shaggy brown hair flopped over his forehead as he ran from one activity to the next, and his grin turned wider and wider as the day went on.

After dinner, he was back in bed, worn out but happy. He had made dozens of new friends, people just like him, people with HIV and AIDS who simply wanted to have fun.

On the third night of camp, we held a small candlelight ceremony before the kids went to bed. In a circle, we lit a single candle and passed it around. Each child had a chance to speak. Ryan was shy. But when the candle was passed to him, he looked at his fellow campers, nodded his head and said, “You know, this is the best week of my life.”

At that moment, I knew that Camp Heartland would be a success.

Even though he was very ill, Ryan had a great week, seven days of pure, worry-free fun. Hampered by an overwhelming fatigue, he missed many camp activities. But it didn’t really matter. He was liberated. Coming to Camp Heartland and meeting a group of young people who were not afraid to play football with im, to share meals with him, to hug him – it was just what he needed.

Ryan went home from camp empowered. Sure he was from a great family and went to a good school. But the secret that he was forced to live with made him a prisoner in his hometown. “I’m tired of living a lie,” he told his mother when he got home. “I want to tell my neighbors and my friends. If they don’t like me for who I am, then they weren’t really my friends to begin with. I want to tell the whole world I have AIDS.”

And he did just that. Ryan began speaking out at school and in the local media, sharing this painful secret about his illness. Soon, all of Whiteville knew that Ryan had AIDS. As the news began to spread, he appeared with me on the “CBS Morning Show,” and millions knew.

The people of Whiteville did not step back in fear. They were not angry, they were not suspicious. Instead, they took the time to learn about HIV. With words and actions, they assured him, “We’re not afraid of you, Ryan. You will always be our friend.” That small town stepped up and made a lifelong commitment to help and support Ryan Chedester, because he was one of their own.

Basking in the support of his family and community, Ryan was a carefree boy. He loved fishing. He loved riding his four-wheeler. He loved sports, video games, “Beavis and Butthead.” He would float around in a swimming pool for hours without interruption. He drank so much Dr. Pepper I wanted to buy stock in the company. Ryan was a kid living with AIDS. But first and foremost, he was a kid.

In August of 1995, Ryan was struck down with cryptosporidium, a water-borne parasite he contracted by drinking tap water in his town. Ryan and his mother received the news of his illness while at a Camp Heartland session in California. Ryan’s prognosis was grim. He was ill as anyone I’ve ever seen. This was AIDS, this was hemophilia, this was cryptosporidium – all combined. No one deserved to go through that.

For six months, off and on, Ryan stayed at Tulane University Hospital in downtown New Orleans. Whenever I would visit, I tried to take his mind off his pain and despair. Sometimes his mom and I would sneak him out of the hospital and we would go shopping or to a movie or just drive around town, his mother behind the wheel and Ryan wedged between us in the front seat. Even if it was just an hour, it was good for him to get out.

***

I saw a play awhile ago called “The Yellow Boat” written by David Saar about his son, a boy with hemophilia and AIDS. During the play, the boy tells a Scandinavian folk tale about three colored boats on the ocean. According to the legend, the red boat carried faith, the blue boat carried hope, and the yellow boat carried love. At the end of the day, the red boat sailed back to the harbor, along with the blue boat. But the yellow boat sailed up to the sun.

I can imagine Ryan Chedester telling his parents, “Daddy, you be the red boat, and Mama, you be the blue boat. But I will be the yellow boat.”

Ryan’s yellow boat has sailed to the sun, his yellow boat has sailed to the heavens, his yellow boat has sailed to god. And Ryan’s light will shine on us for many years to come.