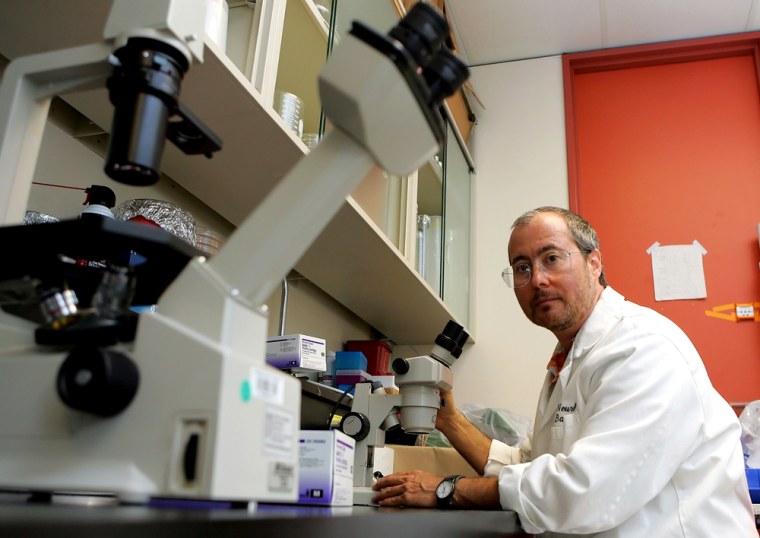

As someone who studies brain development and regeneration, Stanford University neurobiologist Ben Barres feels qualified to comment on whether nature or nurture explains the shortage of women working in the sciences.

But it wasn't just his medical degree from Dartmouth, his Ph.D from Harvard and his research that inspired him to write an article blaming the persistent gender gap on institutional bias.

Rather, it was that for most of his academic life, the 51-year-old professor who now wears a beard was once known as Dr. Barbara Barres, a woman who excelled in math and science.

"I have this perspective," said Barres, who switched sexes when he started taking hormones in 1997. "I've lived in the shoes of a woman and I've lived in the shoes of a man. It's caused me to reflect on the barriers women face."

Barres' opinion piece, published in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature, was a response to the debate former Harvard president Lawrence Summers reignited last year when he said innate sexual differences might explain why comparatively few women excelled in scientific careers.

Summers' clashes with faculty — including over women in science — led to his resignation, though not before he committed $50 million on childcare and other initiatives to help advance the careers of women and minority employees.

Even so, Barres thinks a meaningful discussion of what he calls the "Larry Summers Hypothesis" ended too soon, leaving missed opportunities and a bad message for young female scientists.

"I feel like I have a responsibility to speak out," he said. "Anyone who has changed sex has done probably the hardest thing they can do. It's freeing, in a way, because it makes me more fearless about other things."

In his article, Barres offers several personal anecdotes from both sides of the gender divide to prove his own hypothesis that prejudice plays a much bigger role than genes in preventing women from reaching their potential on university campuses and in government laboratories.

The one that rankles him most dates from his undergraduate days at MIT, where as a young woman in a class dominated by men he was the only student to solve a complicated math problem. The professor responded that a boyfriend must have done the work for her, according to Barres.

Barres makes a point of saying that he never felt mistreated or held back as a woman scientist. At the same time, he wonders if his personal experience somehow shielded him from the more insidious effects of gender bias.

"I wasn't subject to the same stereotype threat because I never identified with women when I was growing up," he said. "In a way that was one of the lucky things for me about being transgender."

Aside from his unique vantage point, the thrust of Barres' article is that neither Summers nor the prominent scientists who defended his position used hard data to back up the claim that biology makes women less inclined toward math and science.

He cites several studies — including one showing little difference in the math scores of boys and girls ages 4 to 18 and another that indicated girls are groomed to be less competitive in sports — to support his discrimination argument.

"If a famous scientist or the president of a prestigious university is going to pronounce in public that women are likely to be innately inferior, would it be too much to ask that they be aware of the relevant data?" he writes in Nature.

"It would seem just as the bar goes up for women applicants in academic selection processes, it goes way down when men are evaluating the evidence for why women are not advancing in science."

Harvard University psycholinguist Steven Pinker, whom Barres names in his commentary as a leading defender of Summers, already has written a letter to the editors of Nature criticizing the piece as "polemic" that "contains numerous falsehoods and scurrilous statements."

Pinker said both he and Summers relied on "a large empirical literature showing differences in mean and variance in the distributions of talents, temperaments, and life priorities" among men and women to explain why women might be underrepresented in some scientific disciplines.

"He should learn to take scientific hypotheses less personally," Pinker said.