When Sheriff Terry Maketa announced a Colorado inmate was claiming responsibility for a string of bodies across half the country, he proudly credited three retirees with cracking the case.

They have been dubbed “The Apple Dumpling Gang” by admiring members of the El Paso County sheriff’s department, but don’t confuse the three unpaid volunteers with the bumbling dolts from the Disney movie of the same name.

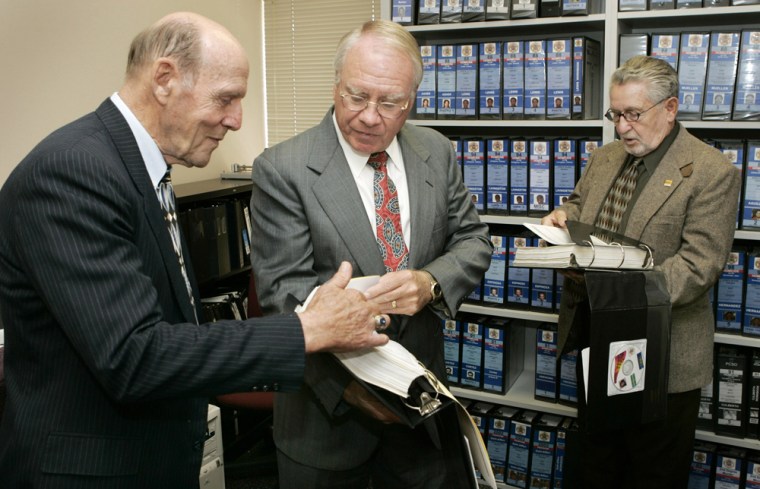

With a combination of experience, finesse, meticulous organization and that most precious of resources, time, Charlie Hess, Lou Smit and Scott Fischer — two former lawmen and a retired newspaper publisher, respectively — helped coax confessions from Robert Charles Browne to as many as 49 murders committed between 1970 and 1995.

So far, authorities have corroborated some of Browne’s claims in six cases.

The sheriff said he had no reservations about turning over sensitive information from the case file to the three volunteers.

“A lot of agencies are probably reluctant to use volunteers in sensitive areas, just because of bias or maybe the threat to full-timers,” Maketa said. But Hess’ deft interviewing skills led the sheriff to give him and the others a shot at Browne in 2002.

‘Looking for something to do’

At the time, Browne, now 53, was serving a life sentence in Colorado for the 1991 murder of a 13-year-old girl, Heather Dawn Church.

“We were sitting around having coffee one morning before coming into the office, looking for something to do, and the subject came up about contacting individuals who had been handled and were potential, or possible serial killers,” Hess recalled.

“And I think Scott asked Lou, ‘You’ve been around forever. Who would be at the top of your list as a potential serial killer that’s already incarcerated?’ And Lou immediately came up with Robert Browne.”

Smit, 71, is a retired Colorado Springs police investigator who had worked on the Church case and always felt there was something strange about the way Browne abducted the girl and left her body in the wilderness.

“The Heather Church murder was a little unusual from the standpoint that it appeared to be a burglary,” Smit said. “When you really think about that, if it was a burglary, all he had to do was go in there and just walk out if she didn’t recognize him or kill her right there. But he took her out, and that always set wrong with me.”

Coaxing the confession

Investigators handed the three a rambling, taunting letter Browne sent to authorities in 2000 in which he hinted at a string of killings.

Over the years that followed, Hess exchanged letters with Browne. Hess and his partners — including Fisher, a 60-year-old former newspaperman and publisher of The Gazette in Colorado Springs — would decipher Browne’s often cryptic notes and delicately, patiently press him for more information.

“When we would receive a letter from Robert, we’d all sit down, we’d kick it around, you know? What’s he trying to tell us? Is there a message here?” Hess said. “Our letters back to him were a composite of our thoughts as to what we thought would turn him on to the point where he would be willing to share more detailed information.”

Press too hard, express disgust or appear to judge Browne, and the killer would clam up. But Hess kept at it, occasionally securing small favors for Browne, such as getting him an outside doctor or a certain book.

It was painstaking work, full of intrigue and frustration. But this was familiar ground for Hess, 79. He spent 10 years in the FBI before joining the CIA, where he said he worked in the shadowy Phoenix Program in Vietnam, a campaign to root out the Viet Cong by assassinating them, capturing them or persuading them to defect.

‘Where do we go?’

A typical exchange with Browne:

“I will not hand it to (authorities) on a golden platter with nothing to gain for my efforts. ... There are eight other states that may be interested; Colorado only has nine points of interest. Louisiana has seventeen. ... Dispatch and disposal may have taken place in Colorado, but procurement may have taken place elsewhere,” Brown wrote in December 2002.

Hess wrote back: “I do not believe I would put the details on a gold platter without first receiving the assurances you consider important. On the other hand it makes one wonder why you wrote in the first place? ... So Robert, where do we go from here?”

Less than two months later, Hess and company got an answer from Browne in a letter that read: “Try the missing persons files on a young Army wife.” And six months after that, he confessed during a prison interview to the slaying and dismemberment of Rocio Sperry, a 15-year-old Army bride who disappeared from Colorado Springs in 1987.

The greatest asset

In early 2003, he told the cold-case investigators about two other murders, in Texas, and still another, in Oklahoma. Last year, he confessed to three more, all in his home state of Louisiana.

By late July, Browne had agreed to plead guilty to Sperry’s murder — and the sheriff was ready to tell the public that one of the nation’s most prolific serial killers might be behind bars in Colorado. Authorities from Arkansas to Washington state went to work, trying to corroborate Browne’s claims.

Maketa’s use of volunteer detectives is rare, said Ed Nowicki, director of the International Law Enforcement Educators and Trainers Association. He said any department would envy the lineup of Fischer, Hess and Smit.

“There’s no shortcut to experience. Here you add one and one and one and it equals 10,” Nowicki said. “Their motivation is from the heart, not from the wallet.”

Maketa said his volunteers had something his full-time squad did not: time. They didn’t punch a clock and they weren’t carrying active cases that demanded attention.

“They could sit and have coffee and talk about their plan,” he said. “That is probably the greatest asset that a group of ‘The Apple Dumpling Gang’-type can bring to the equation. They’re not in a rush.”

Apple Dumpling Gang not done

For their part, the three say they do not deserve too much credit. They say the sheriff was always supportive, and the full-time staff helped them chase leads and guided them through a minefield of legal technicalities.

The sheriff is now fielding calls from other agencies about his use of volunteers. With 602 full-time employees, the department relies on some 450 volunteers who take part in searches, handle clerical duties and perform other tasks.

For the Apple Dumpling Gang, there is still work to be done to corroborate what Browne told them. Fischer said he hopes Browne’s confession also encourages departments across the country to open up cold cases.

“There’s a lot of victims out there that Robert Browne didn’t kill,” he said.