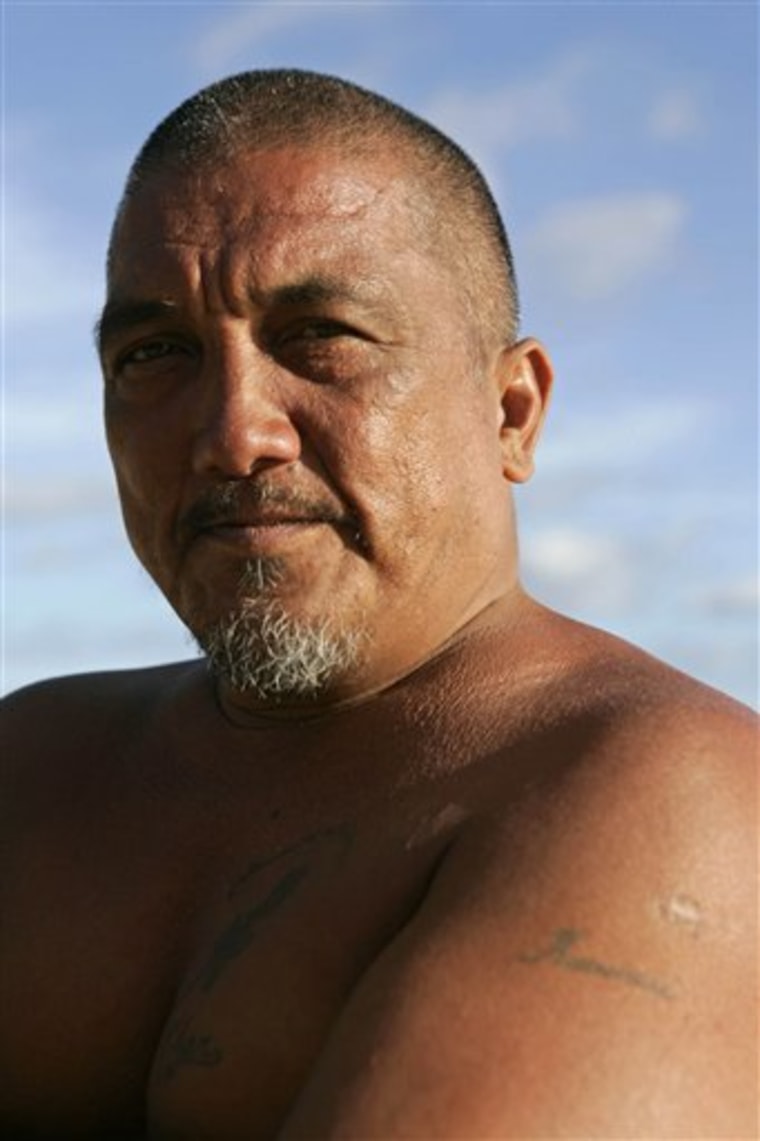

Bert Bustamante and his family look as if they are enjoying a vacation at the beach, with kids swimming in the ocean, fish frying on the grill and radio music floating in the air.

A closer look, though, reveals the truth: Life on the beach is about all Bustamante and his neighbors have.

They are homeless in paradise.

Just up the coast from a major luxury resort, at least 725 homeless people — by one community group’s count — are living on a 16-mile stretch of Oahu’s western shore, a pristine beach where oceanfront lots would cost millions.

Armed with city-issued camping permits, the homeless use beach showers and sleep in tightly packed tents. Dinner is bought with food stamps.

Some end up on the beach because of drug problems, mental illness, sudden misfortune or simple economic necessity. Some have jobs in recycling centers, restaurants or hotels but do not make enough to rent an apartment or buy a house on Hawaii’s main island, where the median price for a single-family home is $635,000. Others simply want to live this way.

For some, it beats concrete any day

Many say living out in the sun beats a cold patch of concrete in an alley downtown.

“If somebody would come out here and take my family to somewhere we could afford it, I would take that opportunity,” says the 48-year-old Bustamante, who has been living in Nanakuli Beach Park since last fall. “Life is good out here, but I still don’t want to be here. I don’t belong here.”

Bustamante admits he has done drugs in the past and ended up on the beach with his wife and nine kids after losing his rented house and job.

Roxy Bustamante, his wife, is the breadwinner, working at a pizza delivery call center and making about $2,000 a month. She says they are stuck on the beach because her husband needs to watch the kids, and she doesn’t make enough to move to a more permanent home.

In other states, too

The homeless sleep on the beach in other warm-weather states as well. Between 200 and 300 people live on the sand near Jacksonville, Fla., and in Santa Monica, Calif., some of the city’s 2,000 homeless spend the night on the beach, though authorities do not let them set up tents. But the line of encampments along Oahu’s Waianae Coast is particularly extensive.

Kaulana Park, appointed by Gov. Linda Lingle in July to help the state’s homeless, estimated the number of homeless people in Hawaii at fewer than 10,000.

The islands’ homeless problem reached a crisis in March when Honolulu officials cleared hundreds of homeless people from a city beach park. A dockside warehouse had to be converted into a temporary shelter. A 200-person shelter is expected to open in November in Kalaeloa, along the coast.

The camps along the Waianae coastline look like a Third World village. A basketball hoop hangs from the side of a tree, and grills substitute for ovens. Children ride their secondhand bicycles through an obstacle course of benches and old trucks. The youngest children wear life vests instead of shirts so they can safely play in the water.

‘Three seconds from the ocean’

“I like living on the beaches. We’re like three seconds from the ocean, so anytime we want, we can jump in the water and have a good time,” says 11-year-old George Orpilla. “What I don’t like about being on the beach is that there’s no electricity, there’s no hot water, there’s no TV. I really miss TV.”

Nearby residents have complained to the governor and mayor, with some saying they are afraid of the homeless people.

“Leaving them homeless and letting them live on the beaches isn’t going to improve their situation,” said Victor Rapoza, a Waianae resident for 48 years. “Get them in a rehabilitation center.”

But every Friday, the tent-dwellers head to a City Hall annex to renew their one-week permits. Camping permits are available on a first-come, first-served basis to anyone who requests them. City officials say they cannot say no, because it is public land.

“They think we’re all criminals because we live on the beach. It’s a vicious cycle. I’m just trying to survive, make it to the next day,” says 19-year-old Josh Andrus, who is disabled from a car accident and has lived on the beach for four months. “The only thing you can do is keep your chin up and remember you are in paradise.”