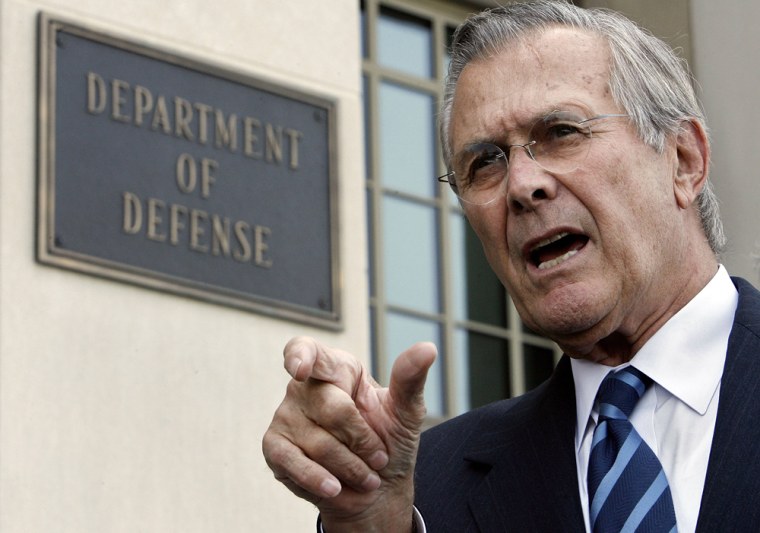

Former White House chief of staff Andrew H. Card Jr. on two occasions tried and failed to persuade President Bush to fire Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, according to a new book by Bob Woodward that depicts senior officials of the Bush administration as unable to face the consequences of their policy in Iraq.

Card made his first attempt after Bush was reelected in November 2004, arguing that the administration needed a fresh start and recommending that Bush replace Rumsfeld with former secretary of state James A. Baker III. Woodward writes that Bush considered the move but was persuaded by Vice President Cheney and Karl Rove, his chief political adviser, that it would be seen as an expression of doubt about the course of the war and would expose Bush to criticism.

Card tried again around Thanksgiving 2005, this time with the support of first lady Laura Bush, who, according to Woodward, felt that Rumsfeld's overbearing manner was damaging to her husband. Bush refused for a second time, and Card left the administration in March, convinced that Iraq would be compared to Vietnam and that history would record that no senior administration officials had raised their voices in opposition to the conduct of the war.

The book is the third that Woodward, an assistant managing editor at The Washington Post, has written on the Bush administration since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The first two were attacked by critics of the administration as depicting the president in a heroic light. But the new book's title, "State of Denial," conveys the different picture that Woodward paints of the administration since the invasion of Iraq in March 2003. Excerpts of the book will be published in the Sunday and Monday editions of The Post.

Internal, public statements at odds

Woodward writes that there has been a vast difference between what the White House and the Pentagon knew about the situation in Iraq and what they have been saying publicly. In memos, reports and internal debates, administration officials have voiced their concerns about the conduct of the war, even while Bush and Cabinet members such as Rumsfeld and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice have insisted that the war was going well.

In May, Woodward writes, the intelligence division of the Joint Chiefs of Staff circulated a secret intelligence estimate predicting that violence in Iraq will not only continue for the rest of this year but also increase in 2007.

"Insurgents and terrorists retain the resources and capabilities to sustain and even increase current level of violence through the next year," said the report, which was distributed to the White House, the State Department and intelligence agencies.

The report presented a similarly bleak assessment of oil production, electricity generation and the political situation in Iraq.

"Threats of Shia ascendancy could harden and expand Shia militant opposition and increase calls for coalition withdrawal," the report said.

Several warnings on Iraq

Woodward writes that Rice and Rumsfeld have been warned repeatedly about the deteriorating situation in Iraq.

Returning from his assignment as the first head of the Iraq postwar planning office, retired Lt. Gen. Jay Garner told Rumsfeld on June 18, 2003, that the United States had made "three tragic mistakes" in Iraq.

The first two, he said, were the orders his successor, L. Paul Bremer, had given banning members of the Baath Party from government jobs and disbanding the Iraqi military. The third was Bremer's dismissal of an interim Iraqi leadership group that had been eager to help the United States administer the country in the short term.

"There's still time to rectify this," Garner said. "There's still time to turn it around."

But Rumsfeld dismissed the idea, according to Woodward. "We're not going to go back," Rumsfeld said.

A year later, Rumsfeld received even more blunt criticism from Steve Herbits, a longtime friend who, according to Woodward, has served as an informal adviser to Rumsfeld since he became defense secretary. In a seven-page memo in July 2004 titled "Summary of Post-Iraq Planning and Execution Problems," Herbits listed a series of questions for Rumsfeld:

- "Who made the decision and why didn't we reconstitute the Iraqi Army?"

- "Did no one realize we were going to need Iraqi security forces?"

- "Did no one anticipate the importance of stabilization and how best to achieve it?"

- "Why was the de-Baathification so wide and deep?"

He then described "Rumsfeld's style of operation," which he said was the "Haldeman model, arrogant," referring to President Richard M. Nixon's White House chief of staff H.R. "Bob" Haldeman. "Indecisive, contrary to popular image. Would not accept that some people in some areas were smarter than he. . . . Trusts very few people. Very, very cautious. Rubber glove syndrome -- a tendency not to leave his fingerprints on decisions."

Woodward does not say how Rumsfeld responded.

Misgivings in the military

Some of the highest-ranking officers serving under Rumsfeld had similar misgivings about Iraq.

In March, Gen. John P. Abizaid, the senior U.S. commander for the Middle East, met privately with Rep. John P. Murtha (D-Pa.), who had criticized the Bush administration's approach to Iraq as "a flawed policy wrapped in illusion" and called for withdrawal. Murtha was attacked by the White House for "endorsing the policy positions of Michael Moore and the extreme liberal wing of the Democratic Party."

According to Murtha, Woodward writes, Abizaid raised his hand, held his thumb and forefinger a quarter of an inch from each other and said, "We're that far apart."

But, according to Woodward, Rumsfeld made sure that his choices for chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff -- Air Force Gen. Richard B. Myers and Marine Corps Gen. Peter Pace -- were not people who would directly challenge him.

Woodward writes that just before Pace was named chairman, he was visited by an old friend, Marine Corps Gen. James L. Jones, the NATO commander. Jones expressed concern that Pace would even want to be chairman. "You're going to face a debacle and be part of the debacle in Iraq," he said. U.S. prestige was at a 50- or 75-year low in the world. Jones said he was so worried about Iraq and the way Rumsfeld ran things that he wondered if he himself should not resign in protest.

And, he told his friend, according to Woodward: "You should not be the parrot on the secretary's shoulder."

Woodward writes that he called Jones at NATO headquarters in Belgium and that Jones confirmed the story.

Woodward describes Rice as frequently at odds with Rumsfeld when she served as national security adviser, and her staff as increasingly concerned about the lack of a strategy for winning the war in Iraq.

When she became secretary of state in 2005, Rice asked Philip D. Zelikow, an old friend whom she had brought on as an adviser, to travel to Iraq to assess the situation. On Feb. 10, two weeks after Rice became secretary, Zelikow presented her with a 15-page, single-spaced memo.

"At this point Iraq remains a failed state shadowed by constant violence and undergoing revolutionary political change," he wrote.

A 'brush-off' from Rice

"State of Denial" adds new information about Rice's role in the Bush administration's efforts to combat terrorism in the months before the Sept. 11 attacks. That subject became a source of controversy this week after former president Bill Clinton accused "President Bush's neocons" and other Republicans of ignoring Osama bin Laden until the attacks; Rice responded angrily to the charge.

Woodward writes that on July 10, 2001, then-CIA Director George J. Tenet became so concerned about the communications that intelligence agencies were receiving indicating a terrorist attack was imminent, he went to the White House with counterterrorism chief J. Cofer Black -- without an appointment -- to meet with Rice, then the national security adviser. He and Black hoped the meeting would alert Rice to the urgency they felt.

But Tenet and Black felt that Rice gave them "the brush-off," according to Woodward, telling them that a plan for coherent action against bin Laden was already in the works. Woodward writes that both Tenet and Black felt that the meeting was the starkest warning the White House was given about bin Laden.

Key role for Kissinger

The book describes Tenet as feeling that Rice could have gotten through to Bush on the bin Laden threat but that she had not understood it in time. Black described his frustration more directly, according to Woodward: "The only thing we didn't do was pull the trigger to the gun we were holding to her head."

Woodward writes that former secretary of state Henry A. Kissinger has played a key role as an outside adviser to Bush on the Iraq war. Kissinger, according to Woodward, sees Iraq through the prism of his experience in the Nixon administration during the Vietnam War, and has counseled Bush to "stick it out" and not even entertain the idea of withdrawing troops.

At one point, to emphasize his position, he gave Michael Gerson, then a White House speechwriter, a copy of a memo he wrote to Nixon in September 1969. "Withdrawal of U.S. troops will become like salted peanuts to the American public; the more U.S. troops come home, the more will be demanded," Kissinger wrote.

Diminishing role for Cheney

Unlike Woodward's previous books, "Bush at War" and "Plan of Attack," "State of Denial" does not focus on Bush. Woodward writes that Bush, who agreed to be interviewed for the first two books, declined this time.

Woodward also spends little time on Cheney, writing that since 2005 the vice president has been perceived as having no visible role in Iraq policy. He describes Cheney's associates as saying he was "lost" without his former chief of staff, I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby, who resigned after he was indicted for his role in the Valerie Plame leak case.

According to Woodward, Cheney relied on his wife, Lynne, and his daughter Liz for advice, and some close friends believed he "became increasingly removed from reality."