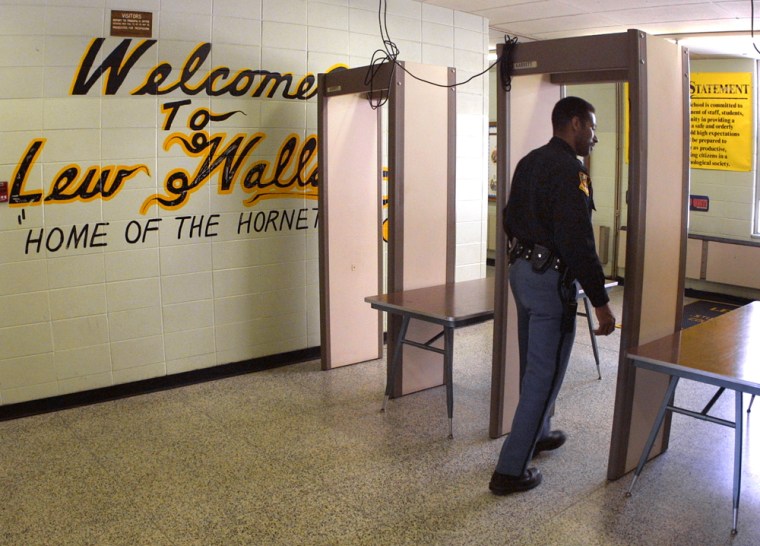

Metal detectors, threat-evaluation software, police officers -- hundreds of American schools have added tighter security since 1999’s attack at Colorado’s Columbine High School.

But these solutions "are not likely to be effective," and are potentially harmful, according to federal researchers who conducted the most thorough study of school shootings across the nation.

Of what value is a metal detector, the researchers asked, when an attacker is willing to kill others and take his or her life?

Or threat-evaluation software, when most attackers do not make a threat before an attack?

Or a SWAT team, when most attacks last only a few minutes and end before police arrive?

Instead of relying solely on physical security, the researchers suggest, schools should be paying more attention to listening to students, discouraging and discovering attacks while they’re still in the planning stages.

After the nation’s third deadly school attack in a week, one of the researchers said Monday that he was ambivalent about encouraging every one of the 100,000 schools in the nation to add metal detectors.

“Because you’ve had three school shootings in this country, is that a reason to make sure that every school in the country has a metal detector?” said the researcher, William Modzeleski, director of the Safe and Drug-Free Schools Program for the U.S. Department of Education, which studied school shootings with researchers from the U.S. Secret Service. “Would it have stopped what happened?”

How else can schools prevent attacks?

The most detailed study of school shootings was done by the U.S. Secret Service and the U.S. Department of Education. The researchers studied 37 attacks, and interviewed 10 of the perpetrators, for their 2002 report.

Their advice? Schools should:

- Encourage students to report what they hear, and to have an adult they can confide in, because attackers often disclose their plans to other students, but rarely to adults.

- Watch for behavior such as gathering weapons or making plans, because attackers rarely “just snap” in a spur-of-the-moment attack.

Profiling doesn't work

- Not wait for a student to make a threat, because most attacks were not preceded by explicit threats.

- Respond aggressively to bullying, often a motive behind the attacks.

- Develop crisis plans that focus on preventing violence, not just responding to it, and develop connections to the police department and first responders as well as mental health departments and community groups.

- Avoid profiling, or looking for a certain “type” of student who might commit an attack, because the attackers have been racially diverse, and had different family backgrounds, social standing and school achievement records. Too many innocent students will fit a profile, and too many attackers will not. (Most of the attackers, but not all, have been male, but that doesn't narrow down the population much.)

“The thrust of our recommendations is not that metal detectors and the like are irrelevant,” one of the researchers, psychologist Randy Borum of the University of South Florida, said Monday. “They’re target-hardening. But they’re insufficient.”

'Walked right through it'

Is it practical, or effective, to add physical security in Cazenovia, Wis., or in Bailey, Colo., or at the one-room Amish schoolhouse in Lancaster County, Pa., each the scene of a shooting in the past week.

“We’re cognizant of the fact that metal detectors do keep out some type of guns, but I think it’s a balancing act,” Modzeleski said. “Some schools with a weapons problem can benefit from them. But they can send a wrong message and have an adverse effect on the climate of the school. It also sends a message that if you have a metal detector, you’re safe. And I’m not sure that’s so.”

Modzeleski noted that the high school in Red Lake, Minn., where seven were killed by a student last year, had a metal detector and a security guard. The gunman, Jeffrey Weise, shot and killed the guard, then walked down the hall shooting students and a teacher.

In Pearl, Miss., shooter Luke Woodham was asked by Secret Service investigators what he would have done in 1997 if he’d encountered a metal detector. “He would have walked right through it,” Modzeleski recalled.

The key questions for parents and school administrators to think about, the researchers said, are: What patterns of behavior might be of concern? What should someone do if one notices such behavior? And what should the person or school do if such behavior is reported to them?

“Rather than trying to determine the ‘type’ of student who may engage in targeted school violence,” the researchers found, “an inquiry should focus instead on a student’s behaviors and communications to determine if that student appears to be planning or preparing for an attack. Rather than asking whether a particular student ‘looks like’ those who have launched school-based attacks before, it is more productive to ask whether the student is engaging in behaviors that suggest preparations for an attack, if so how fast the student is moving toward attack, and where intervention may be possible.”

It may sound implausible to think that a teenager’s plan to shoot up the school can be detected and interrupted. Nothing is certain, the researchers said, but they found some hope in their interviews with the shooters.

In Bethel, Alaska, in 1997, Evan Ramsey told many classmates what he intended to do. He told so many that a crowd gathered in the library balcony to watch. But no one passed that word to an adult.

Ramsey was asked, “If the principal had called you in and said, ‘This is what I’m hearing,’ what would you have said?”

“I would have told him the truth.”

A pattern of targeting girls?

School attacks, although causing great fear, are incredibly rare.

Even including homicides caused by drug deals or other disputes, homicides happen only about 12 to 20 times a year at schools in the U.S., down from about 30 a year in the 1990s, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Less than 1 percent of all homicides among school-age children occur on or around school grounds, or on the way to and from school, the CDC found. And general school violence -- assaults usually -- have fallen by about half since 1992.

Although all school attacks may be grouped together in the public mind, experts aren’t sure how to classify the attack Monday in Lancaster County by truck driver Charles Carl Roberts IV, or last week in Bailey, Colo., where Duane Roger Morrison, 53, held six girls captive at Platte Canyon High School before killing one of them.

Because they were carried out by adults, perhaps those really aren’t school shootings at all, in the classic sense, researchers suggest. Maybe the shootings could just have well have happened at a shopping mall or any other gathering place. On the other hand, Roberts was said to have told his wife he was seeking revenge for something that happened at the school decades ago, when he was a boy, and to have said he feared he would repeat molestation he had committed in the past. We may never truly know his motive, nor Morrison’s, partly because they both committed suicide.

“When you start to characterize a type of violence only by where it occurs,” you may not be able to draw meaningful conclusions, said researcher Borum, an associate professor in mental health law and policy. “You end up with alleyway violence, shopping mall violence.” For this reason, the Secret Service report excluded attacks where the perpetrator was not a current or former student.

An adult committed the worst school attack in U.S. history, on May 18, 1927, in Bath, Mich. School board member Andrew Kehoe killed his wife, set his farm buildings ablaze and then detonated explosives he had stockpiled for months under the town school.

When rescuers arrived at the Bath school, Kehoe detonated his car filled with metal for shrapnel, killing himself and the school superintendent. In all, Kehoe killed 45 people, including 38 children. He had blamed school taxes for causing the foreclosure of his farm.

A Canadian case may be more similar to the recent adult attacks, in terms of the attackers singling out girls and young women as their victims. In Montreal in December 1989, at the Ecole Polytechnique de Montreal, Marc Lepine separated the men from the women, shouting against feminists. He killed 14 women, and wounded 13 people, including four men, before killing himself.

One of the three attacks in the past week more closely fits the classic pattern, in terms of attacker, possible motive, and an oblique warning.

In Cazenovia, Wis., Eric Hainstock, 15, has been charged with murder in the shotgun death at school of Principal John Klang. Hainstock had complained about being teased by students, and had just been given a disciplinary warning by the principal for having tobacco at school, authorities said.

He had told a friend a few days earlier, authorities said, that the principal would not “make it through homecoming.”